Dwight M. Sabin

Dwight Sabin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chair of the Republican National Committee | |

| In office December 21, 1883 – June 6, 1884 | |

| Preceded by | Marshall Jewell |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Jones |

| United States Senator from Minnesota | |

| In office March 4, 1883 – March 3, 1889 | |

| Preceded by | William Windom |

| Succeeded by | William D. Washburn |

| Member of the Minnesota House of Representatives from the 22nd district 23rd (1883–1884) | |

| Member of the Minnesota House of Representatives from the 22nd district 22nd (1881–1882) | |

| Member of the Minnesota House of Representatives from the 22nd district 20th (1878–1879) | |

| Member of the Minnesota Senate from the 22nd district 15th (1873–1874) | |

| Member of the Minnesota Senate from the 22nd district 14th (1872–1873) | |

| Member of the Minnesota Senate from the 2nd district 13th (1871–1872) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dwight May Sabin April 25, 1843 Marseilles, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 22, 1902 (aged 59) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States • Union |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Dwight May Sabin (April 25, 1843 – December 22, 1902) was an American politician who served as U.S. Senator from Minnesota and in the Minnesota Legislature. He is known for the business ventures of Seymour, Sabin & Co. and the Northwestern Car Company, highly successful enterprises dependent on the highly profitable prison labor contracts he had negotiated with the Minnesota State Government in the 1870s. His election to federal office, in 1883, came following an infamous prolonged dead-lock in the Minnesota State Senate, during which incumbent Senator William Windom failed of re-election[1] following "the worst campaign in the known history of the state."[2]

Early life

[edit]Dwight May Sabin, the elder of the two sons of Horace Carver Sabin and Maria Elizabeth Webster (originally of Fredonia, NY), was born in 1843, in Marseilles, Illinois, where he spent his childhood years.[3]

Horace, Dwight's father, of Windham County, Connecticut, had moved west to establish his own property near Marseille, IL, platted 1853 as a canal town in the expectation of the completion of the Illinois-Michigan Canal. Horace's enterprise was successful, but illness returned the Sabins to Connecticut by 1857, where the family moved into the Sabin's ancestral home, part of the original Connecticut New Roxbury Grant,[4] and descended through the family from the area's earliest white settlers, circa 1686.[3][5]

In 1862, following his grandfather's death, Sabin attended Phillips Academy, studying civil engineering and mathematics, leaving school after a year of coursework to enlist as a Union soldier in the American Civil War. A period review of his life and career from 1883 noted that he arrived at Gettysburg in July, 1863, "on the second day of the decisive and dreadful battle of the rebellion, at the very period when the only regiment from Minnesota in the Army of the Republic was behaving so gallantly on Cemetery Hill,"[6] but this Minnesota reference, and its supposed significance to Sabin, may simply have been a political nod to his recent election to the US Senate at the time of the piece's publication.

While in the Federal Army, Sabin served as aide to the "chief medical officer of General Pleasanton's Cavalry," until several months' "exposure in the field" brought on an unidentified pulmonary illness that took him from camp duty to a clerkship in "the Third Auditor's Office" (Auditor of the War Department[7]) in the US Treasury Department in Washington, DC. When his father died in 1864 Sabin, just twenty, was discharged and returned to Connecticut to help his mother manage his father's estate. Sabin took on the management of the family property in Windham County, while his mother, accompanying his brother Jay, returned to Illinois to take on management of the Illinois farm.[8][9] The next three years were spent "cutting his woodlands into lumber and disposing of the same".[6] in Connecticut

In 1867 his doctor suggested Sabin relocate for the sake of his health. After spending time with his family in Illinois, he moved to Minnesota, where he settled in Stillwater and became involved in lumber and manufacturing interests.

Seymour, Sabin & Co. and the Stillwater Prison

[edit]In 1868, Sabin embarked on a new business venture as the firm of Seymour, Sabin & Co. This new company was contracted with the State of Minnesota to leverage the labor force at the recently established Stillwater Prison.

The labor contract system at Minnesota's Stillwater prison had begun in 1859 with John B. Stevens, a manufacturer of windows and blinds, who had leased the prison workshop from the state, taking over the labor and paying what was then a generous seventy-five cents a day for each full-time worker. But Stevens was forced to declare bankruptcy when his mill burnt down in 1861, and George M. Seymour, a manufacturer of flour barrels, moved in and took over the prison contract, establishing "a wage for a day's work from each prisoner which was scaled to advance from thirty to forty-five cents over a five-year period."[10] 1868 was the first year of record in which a warden protested the exploitative aspects of this system, arguing that, at the very least, "inmates be allowed to work for the benefit of the state rather than for private concerns."[10] It is unclear whether the warden's protests were prompted by the formation of the new company, with Seymour bringing Sabin into the business, or if these protests prompted the formation of the new company. Whichever the case, Seymour, Sabin & Co. were swift to consolidate and expand their business venture. By 1871 the firm's sales had topped $135,000.[10]

Initially the business manufactured doors, window sashes, cooperage (barrels) and the like, a logical progression from Sabin's lumber interests. In 1874 the firm expanded to include a foundry and boiler room, allowing for the production of agricultural implements.[11] The firm began producing threshing machines in 1876, and soon could pride itself as the largest manufacturer of the world famous model "Minnesotan Chief" thresher. Profits topped three hundred thousand dollars by 1881.[10] Sabin himself was described that year as a man "very suggestive of potential force, stored ready for use. He isn't much of a talker. His power is tangible."[12]

By 1882, Sabin was the "prime organizer of the Northwestern Car Company, with capital of $5,000,000," (a coterie which included "'certain wealthy persons' representing large railroad interests"[10]) which then purchased Seymour, Sabin and Co., and elected Sabin president of this new business.[11] With an additional almost twelve hundred civilians employed in the prison shops (constructed ...) as well as in and around the extensive yards and workshops that had proliferated outside the prison walls, Sabin appeared poised to take charge of a manufacturing operation at a scale beyond, at least, that ever imagined by the prison inspectors of 1884, who marched through the conglomeration of workshops declaring, ""It was never expected when the contract for prison labor was made, that the Manufacturing Co. of Seymour, Sabin & Co. would develop into the mammoth N.W. Manufacturing & Car Co."[10]

But before Sabin could solidify his role at the summit of this behemoth, political events intervened. Incumbent Minnesota US Senator William Windom undermined his re-election campaign, and Sabin, unexpectedly, was put up as US Senator in his place. Resignation from active leadership of his new business venture would be a requirement for this new role.

Political career

[edit]

The Minnesota State House

[edit]Sabin first became politically active in Minnesota at the State level when he was elected to the Minnesota Senate in 1871, participating in Minnesota's 13th Legislative Session as representative of the Chisago, Kanabec, Pine, and Washington Counties.

In 1872 and 1873, following county reapportionment, he was re-elected, this time as State Senator, for District 22, Washington County (which included his new hometown, Stillwater). Following a break of four one-year terms, he returned to elected office in 1878, 1881, and 1882, as a member of the Minnesota House of Representatives (again for Washington County), winning election to both Minnesota's Houses of State a total of six times.[9] Additionally during this period, Sabin served as a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1872, 1876, 1880, and 1884, and would sit as Committee chair of the Republican Party from 1883 to 1884.[8] He appears to have been a popular, if not outstanding figure.

The 1883 State House Vote for US Senator

[edit]Sabin's election as US Senator in early 1883 followed the chaos that incumbent William Windom, a strong advocate of railroad regulation, had brought upon his own re-election. Following 1880, when Windom had effectively abandoned his place (and his Committees) in the US Senate for an unsuccessful presidential run, he did not return to retake his 'own' seat under ideal circumstances. By the 1883 elections, he had "antagonized in various ways a large number of his political associates,"[11] a loss of support that became amply clear in the first round of senatorial balloting. The New York Times, reporting in the aftermath, called it "the worst campaign in the known history of the state."[2]

The first round of voting (US senators being voted in, at the time, through the State House) was taken January 16, 1883, and tallied as follows, with no quorum (63 votes) reached:

| William Windom (R) 45

Thomas Wilson (D) 25 Gordon E. Cole (R) 6 Charles F. Kindred (R) 4 Cushman K. Davis (R) 2 Lucius F. Hubbard (R) 2 Thomas Armstrong (R) 2[11] |

Windon, in DC as this vote was cast, immediately got on a train and headed back to his state, but it was too late. Over the next weeks, a series of indeterminate votes was cast. On January 31, 1883, Sabin's name appeared on the ballots for the first time, receiving a surprising 17 votes. Just two weeks later, on February 17,Sabin would receive 81 votes, and take the election.

United States Senator from Minnesota

[edit]Sabin served from March 4, 1883, to March 3, 1889, in the 48th, 49th, and 50th congresses, chairman, Committee to Examine Branches of the Civil Service (Forty-ninth Congress), Committee on Railroads (Fiftieth Congress),[13] and was involved in legislation regarding railroads, veterans pensions and the development of the Soo Locks (where one lock is named in his honor).

In character, he "made no pretense to oratory, and was not known as a speech-making senator, but rather a hard working member in the interest of his state, especially in the line of transportation."[14]

In 1888 he was not renominated by his party and returned to his business pursuits. Sabin charged that bribery had impacted the vote, but these charges were never verified.

Personal life

[edit]

Sabin married twice, first, to Ellen Amelia Hutchins[6] and second, on July 1, 1891, to Jessie Larmon, daughter of Asabel and Susan Slee of Paducah, Kentucky.[3]

E. Amelia Hutchens (b. May 1, 1844)[15] was the adoptive daughter of a doctor from Danielson, Connecticut, who married Dwight sometime between his return from his wartime service in D.C. and his departure for Minnesota. For their family, Dwight and Ellen adopted, first, the sisters Blanche and Ethel (children of John B. Raymond of Fargo, a former congressional delegate for the Dakotas.[16]). Later they added a third child to their family, Ada Chambers,[17] the young daughter of a Sabin relative.[18]

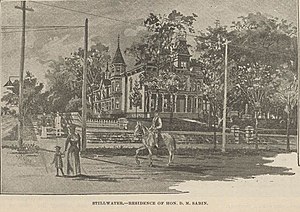

"All Stillwater believed them to be a happy pair."[18] In the early 1870s Sabin constructed a palatial home at the northeast corner of Laurel & Third streets in Stillwater. This was the first private residence in Stillwater to boast electric lights—Sabin had installed cables that ran from the Prison's powerhouse to his home. Wired throughout, visitors would “gaze on the wonderful Aladdin Cave lights and soon it was the talk of the country about the marvelous light that was to be seen both day and night at the stately Sabin home.”[16] This socially adept couple seemed to make a smooth transition to Washington life following Sabin's election as US Senator. Together they were active participants in the social scene, the grand dinners, the gala birthday parties, the delegations to formal occasions such as Grant's funeral.[19] "Socially, Mrs. Sabin is a most fascinating lady," the New York Times reported, "in Washington she gave weekly receptions which were among the most popular given by any lady in that city, and were attended by the most distinguished people."[18]

When Dwight entered a petition for divorce on the grounds of misuse of alcohol and morphine, the news made the front page of the New York Times. Mrs. Sabin had been hospitalized in "an asylum for inebriates" in Flushing, New York. The proceedings, which followed directly on Sabin's loss of his Senate seat, had been kept quiet until the last days of his office. The Times, which had in past coverage described Sabin's political talents as mediocre,[20] and been unstinting in their reports on his financial machinations, approached this sad domestic story from a widely sympathetic standpoint. This stood in high contrast other reports of the period, which painted a rather more dramatic picture of Mrs. Sabin, villainously committed against her will,[21] "Senator Sabin has acted generously by her in his provisions for her present and future comfort." Neither Mrs. Sabin, or her friends and family, would oppose the suit. Sabin's conduct in the matter, "has been all that could be expected under the melancholy circumstances of the case."[21]

Jessie Swann was the widow of W. G. Swann of St. Paul.[16][22] She was with Sabin in Chicago at the time of his death, "unexpected heart failure," on December 22, 1902, at the Auditorium Annex.[3] They had been living in Duluth for two years at that time,[23] near the home of daughter Ethel, now married to T.C. Phillips. The over-magnificent Sabin mansion was left empty after Mrs. Sabin returned to Duluth, and ultimately pulled down in 1918 for its timber.[16]

He is the namesake of the city of Sabin, Minnesota.[24]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "D.M. Sabin Dies Suddenly: Former Minnesota Senator Succumbs to Heart Failure (Special to the Globe)". Saint Paul Globe. 23 Dec 1902. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Senator Windom Beaten: Dwight M. Sabin Elected As His Successor". New York Times (1857-1922). 2 Feb 1883. ProQuest 94115420.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard (1904). The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans ... Biographical Society. p. 65.

- ^ "Connecticut Towns in the Order of their Establishment". CT.gov - Connecticut's Official State Website. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Titus, Anson (1882). The Sabin family of America: the four earliest generations. (Repr. [with additions] from the New Eng. hist. and geneal. register).

- ^ a b c Neill, Rev. Edward D. (1883). Northwest Review: A Biographical and Historical Monthly. Saint Paul, MN: Review Company. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Munden, Kenneth White (1998). The Union: A Guide to Federal Archives Relating to the Civil War. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. p. 315.

- ^ a b Smalley, Eugene Virgil (1896). A history of the Republican party from its organization to the present time: to which is added a political history of Minnesota from a Republican point of view and biographical sketches of leading Minnesota Republicans. Author. p. 323. hdl:2027/umn.31951002360569k.

- ^ a b "Sabin, Dwight May — Legislator Record". Minnesota Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ a b c d e f Dunn, James Taylor (December 1960). "The Minnesota STATE PRISON during the STILLWATER Era, 1853-191". Minnesota History Magazine. 37: 137–151.

- ^ a b c d Minnesota in Three Centuries, 1655-1908: 1870. Publishing society of Minnesota. 1908.

- ^ "Saint Paul: Gossip around the Capitol--The Prison Ring". The Saint Paul Sunday Globe. 20 March 1881. p. 5.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Shutter, Marion Daniel (1897). "Dwight May Sabin". Progressive Men of Minnesota. The Minneapolis Journal. pp. 69–70.

- ^ "Deaths: Mrs. Dwight M. Sabin. Special to the Times". New York Times. 12 Feb 1927. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Peterson, Brent (14 May 2018). "U.S. Senator Dwight M. Sabin". The Stillwater Gazette. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- ^ "Dwight M. Sabin is Stricken". The Minneapolis Journal. 23 Dec 1902. pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c "A SAD DOMESTIC STORY.: EX-SENATOR SABIN COMPLAINANT IN A DIVORCE SUIT". New York Times. 10 Jun 1888. p. 1.

- ^ "A MINNESOTA DELEGATION: The Grant Funeral". New York Times. 2 Aug 1885. p. 2.

- ^ "SENATOR M'MILLAN'S SEAT: MINNESOTA MEN WHO ARE WILLING TO FILL IT. THE SENATOR'S LAUDABLE AMBITION TO SUCCEED HIMSELF NOT LIKELY TO BE GRATIFIED". New York Times. 3 Jan 1887. p. 2.

- ^ a b "MRS. SABIN PROVIDED FOR.: HER FRIENDS ACKNOWLEDGE THE SENATOR'S GENEROSITY". New York Times. 16 Jun 1889. p. 5.

- ^ "Wedding of Ex-Senator Sabin". The Wahpeton Times. 24 Sep 1891. p. 8.

- ^ "D.M. Sabin is Dead: Former United States Senator Passes Away Suddenly at Chicago". Duluth Evening Herald: 1, 15. 1902-12-23 – via Minnesota Historical Society.

- ^ Upham, Warren (1920). Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 118.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Dwight M. Sabin (id: S000003)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- 1843 births

- 1902 deaths

- Republican Party members of the Minnesota House of Representatives

- Republican Party Minnesota state senators

- People from Marseilles, Illinois

- People from Stillwater, Minnesota

- People of Illinois in the American Civil War

- Republican National Committee chairs

- Republican Party United States senators from Minnesota

- 19th-century United States senators

- 19th-century members of the Minnesota Legislature