Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

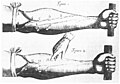

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

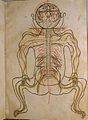

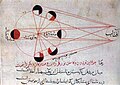

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids and the Buyids in Persia and beyond, spanning the period roughly between 786 and 1258. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. Other subjects of scientific inquiry included alchemy and chemistry, botany and agronomy, geography and cartography, ophthalmology, pharmacology, physics, and zoology.

Medieval Islamic science had practical purposes as well as the goal of understanding. For example, astronomy was useful for determining the Qibla, the direction in which to pray, botany had practical application in agriculture, as in the works of Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-'Awwam, and geography enabled Abu Zayd al-Balkhi to make accurate maps. Islamic mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi, Avicenna and Jamshīd al-Kāshī made advances in algebra, trigonometry, geometry and Arabic numerals. Islamic doctors described diseases like smallpox and measles, and challenged classical Greek medical theory. Al-Biruni, Avicenna and others described the preparation of hundreds of drugs made from medicinal plants and chemical compounds. Islamic physicists such as Ibn Al-Haytham, Al-Bīrūnī and others studied optics and mechanics as well as astronomy, and criticised Aristotle's view of motion. (Full article...)

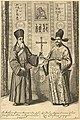

Selected image

An engraving by Albrecht Dürer, from the title page of the Masha'allah ibn Atharī's astronomy treatise De scientia motus orbis (Latin version with engraving, 1504). As in many medieval illustrations, the compass here is an icon of religion as well as science, in reference to God as the architect of creation.

Did you know

...that in the history of paleontology, very few naturalists before the 17th century recognized fossils as the remains of living organisms?

...that on January 17, 2007, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved to "5 minutes from midnight" in part because of global climate change?

...that in 1835, Caroline Herschel and Mary Fairfax Somerville became the first women scientists to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society?

Selected Biography -

Shen Kuo (Chinese: 沈括; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁), was a Chinese polymath, scientist, and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen was a master in many fields of study including mathematics, optics, and horology. In his career as a civil servant, he became a finance minister, governmental state inspector, head official for the Bureau of Astronomy in the Song court, Assistant Minister of Imperial Hospitality, and also served as an academic chancellor. At court his political allegiance was to the Reformist faction known as the New Policies Group, headed by Chancellor Wang Anshi (1021–1085).

In his Dream Pool Essays or Dream Torrent Essays (夢溪筆談; Mengxi Bitan) of 1088, Shen was the first to describe the magnetic needle compass, which would be used for navigation (first described in Europe by Alexander Neckam in 1187). Shen discovered the concept of true north in terms of magnetic declination towards the north pole, with experimentation of suspended magnetic needles and "the improved meridian determined by Shen's [astronomical] measurement of the distance between the pole star and true north". This was the decisive step in human history to make compasses more useful for navigation, and may have been a concept unknown in Europe for another four hundred years (evidence of German sundials made circa 1450 show markings similar to Chinese geomancers' compasses in regard to declination). (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1505 – Death of Paul Scriptoris, German mathematician

- 1520 - Ferdinand Magellan discovers a strait now known as Strait of Magellan

- 1660 – Birth of Georg Ernst Stahl, German scientist (d. 1734)

- 1687 – Birth of Nicolaus I Bernoulli, Swiss mathematician (d. 1759)

- 1821 – Birth of Eduard Heine, German mathematician (d. 1881)

- 1833 – Birth of Alfred Nobel, Swedish inventor and founder of the Nobel Prize (d. 1896)

- 1872 – Death of Jacques Babinet, French physicist (b. 1794)

- 1914 – Birth of Martin Gardner, American mathematician and writer

- 1952 – Death of Hans Merensky, South African geologist and philanthropist (b. 1871)

- 1957 – Birth of Wolfgang Ketterle, German physicist, Nobel laureate

- 1965 - Comet Ikeya-Seki approaches perihelion, passing 450,000 kilometers from the sun

- 1969 – Death of Waclaw Sierpinski, Polish mathematician (b. 1882)

- 2003 - Images of the dwarf planet Eris are taken and subsequently used in its discovery by the team of Michael E. Brown, Chad Trujillo, and David L. Rabinowitz

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus