William Fitzwilliam, 4th Earl Fitzwilliam

The Earl Fitzwilliam | |

|---|---|

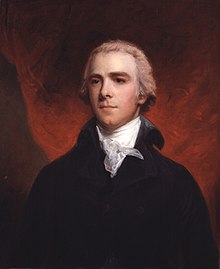

Portrait by William Owen, 1817 | |

| Earl Fitzwilliam | |

| In office 10 August 1756 – 8 February 1833 | |

| Preceded by | William Fitzwilliam |

| Succeeded by | Charles Wentworth-Fitzwilliam |

| Lord Lieutenant of Ireland | |

| In office 13 December 1794 – 13 March 1795 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Prime Minister | William Pitt the Younger |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Westmorland |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Camden |

| Lord President of the Council | |

| In office 1 July – 17 December 1794 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Prime Minister | William Pitt the Younger |

| Preceded by | The Earl Camden |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Mansfield |

| In office 19 February – 8 October 1806 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Prime Minister | Lord Grenville |

| Preceded by | The Earl Camden |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Sidmouth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Wentworth-Fitzwilliam 30 May 1748 |

| Died | 8 February 1833 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouses | Lady Charlotte Ponsonby

(m. 1770; died 1822)Hon. Louisa Molesworth

(m. 1823; died 1824) |

| Children | Charles Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, 5th Earl Fitzwilliam |

| Parents |

|

William Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, 4th Earl Fitzwilliam PC (30 May 1748 – 8 February 1833), styled Viscount Milton until 1756, was a British Whig statesman of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1782 he inherited the estates of his uncle Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, making him one of the richest people in Britain. He played a leading part in Whig politics until the 1820s.

Early life (1748–1782)

[edit]Fitzwilliam was the son of William Fitzwilliam, 3rd Earl Fitzwilliam, by his wife Lady Anne, daughter of Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham. Prime Minister Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, was his maternal uncle. He inherited the two earldoms of Fitzwilliam (in the Peerages of Great Britain and of Ireland) in 1756 at the age of eight on the death of his father. He was educated at Eton, where he became friends with Charles James Fox and Lord Morpeth. His tutor there, Edward Young, wrote to Lady Fitzwilliam on 25 July 1763 of Fitzwilliam's "exceeding good understanding, and ... most amiable disposition and temper".[1] Lord Carlisle (Lord Morpeth), who inherited the earldom, penned a poem about his friends:

Say, will Fitzwilliam ever want a heart,

Cheerful his ready blessings to impart?

Will not another's woe his bosom share,

The widow's sorrow and the orphan's prayer?

Who aids the old, who soothes the mother's cry,

Who feeds the hungry, who assists the lame?

All, all re-echo with Fitzwilliam's name.

Thou know'st I hate to flatter, yet in thee

No fault, my friend, no single speck I see.[2]

In October 1764 Fitzwilliam embarked on his grand tour with a clergyman, Thomas Crofts, nominated by Dr Edward Barnard, headmaster of Eton. Fitzwilliam was not impressed with France, writing that the French were "a set of low, mean, impertinent people" whose behaviour was "so intolerable that it is absolutely impossible for me to associate with them...it is the opinion of everybody, that I had better quit the place immediately".[3] After spending time around France and briefly in Switzerland he returned to England in early 1766, not leaving to continue his grand tour until December. In May 1767 he was in Italy, writing not long after he arrived in Genoa that "I like this place beyond expression".[4] Between the summers of 1767 and 1768 he saw paintings in Verona, the regatta in Venice and the galleries in Padua, Bologna and Florence. Fitzwilliam's taste in paintings was guided by Sir Horace Mann in Florence and William Hamilton in Naples. He returned to England in 1768 with fourteen paintings (eight Canalettos and some of the Bolognese School, such as Guercino and Guido Reni).[5] Fitzwilliam returned to England for the last time in January 1769 after travelling from Naples over the Alps, through Switzerland, Mannheim and Paris.[6]

Fitzwilliam's fortune was substantial but not spectacular. His estate in Milton produced just under £3,000 a year on average for the seven years preceding 1769 (the year Fitzwilliam entered his majority). His other estates in Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Norfolk and the rents from Peterborough added on average £3,600 a year. The combined figure for 1768 from all his properties was £6,900. However, Fitzwilliam inherited a debt of £45,000 with annual charges of £3,300. Fitzwilliam sold his Norfolk properties for £60,000, which was enough to clear the debt on the whole estate.[7]

Taking his seat in the House of Lords, Fitzwilliam attended almost every notable debate, signing nearly every protest which the opposition used but never made a speech during Lord North's premiership.[8] He supported John Wilkes in his fight to keep the seat he was elected to and supported the American Colonies in their dispute with Britain. On 8 July 1776 he asked Lord Rockingham to arrange for a remonstrance to be sent to the King when war broke out in America, so the Americans would see "that there is still in the country a body of men of the first rank and importance, who would still wish to govern them according to the old policy".[9] George Selwyn MP recorded that on 6 March 1782 he had been confronted by Fitzwilliam at the Brooks's and had to listen to Fitzwilliam on the dire state of the nation: "I do not know if he was in earnest, but I suppose that he was. He had worked himself up to commiserate the state of the country, nay, that of the king himself, [so] that I expected every instant that his heart would have burst". When Selwyn asked Fitzwilliam "if there was a possibility of salvation in any position in which our affairs could be placed", Fitzwilliam "asked me ... with the utmost impetuosity, what objection I had to Lord Rock[ingham] being sent for. You may be pretty sure, that if I had any, I should not have made it".[10]

On his uncle Lord Rockingham's death on 1 July 1782 he inherited Wentworth Woodhouse, the largest mansion in the country, and his substantial estates, making him one of the greatest landowners in the country. The Wentworth estate in south Yorkshire was made up of 14,000 acres (57 km2) of farmland, woods and mines yielding nearly £20,000 annually in rents. The Malton estate in the North Riding yielded £4,500 in rent in 1783, rising to £10,000 in 1796 and £22,000 in 1810. An Irish estate of 66,000 acres (270 km2) yielded £9,000 annually in rents. Altogether Fitzwilliam possessed nearly 100,000 acres (400 km2) of British and Irish land with an annual income of £60,000. Added to these were his coal mines: in 1780 his collieries yielded a profit of £1,480; in 1796 £2,978 (with two new collieries yielding another £270). Total colliery profits in 1801 were over £6,000, reaching £22,500 by 1825 (the output of coal was over 12,500 tons in 1799; in 1823 it was over 122,000 tons, making him one of the leading coal owners in the country). In 1827 he calculated that his net income from all his estates was £115,000.[11]

Fitzwilliam, as a landlord, reduced rents and cancelled arrears in bad times, as well as supplying cheap food and giving the elderly free coal and blankets. He also performed his obligations in repairing rented properties and his charitable dispensations were generous but discriminating. His chaplain at Wentworth said that he was "ever giving alms to the poor ... the tale of woe was never told to him in vain". Fitzwilliam also supported friendly societies and savings banks to encourage the poor to practise thrift and self-reliance.[12] Fitzwilliam enjoyed the life of a country gentleman; hunting, racehorse breeding and being a patron of the turf. At the Doncaster races in 1827, the Duke of Devonshire turned up on the first day with a coach and six and twelve outriders, the same as Fitzwilliam. Fitzwilliam appeared the next day "with two coaches and six, and sixteen outriders, and has kept the thing up ever since".[13]

His involvement in local affairs included an appointment as deputy lieutenant of Northamptonshire on 18 February 1793.[14]

Early political career (1782–1789)

[edit]

Fitzwilliam also took up his uncle's role as a major leader of the Whigs. Edmund Burke wrote to Fitzwilliam on 3 July 1782: "You are Lord Rockingham in every thing. ... I have no doubt that you will take it in good part, that his old friends, who were attached to him by every tie of affection, and of principle, and among others myself, should look to you, and should not think it an act of forwardness and intrusion to offer you their services".[15] Charles James Fox wrote on 1 July: "Do not be satisfied with lamenting but endeavour to imitate him. I know how painful it will be to you to exert yourself at such a time, but it must be done...you are one of the persons upon whom I most rely for real assistance at this moment".[16]

Fitzwilliam started to contribute to debates in the Lords, with his first intervention on 5 December 1782 during the debate on the address, intervening to criticise Lord Rockingham's successor as prime minister, Lord Shelburne, on the lack of principle on the concession of American independence.[17] Fitzwilliam was one of the leading supporters of the Fox-North coalition government, being offered the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland and a revived Marquessate of Rockingham by the Duke of Portland. However, Fitzwilliam did not want the office and was not greatly concerned with the new title, which the King would not give anyway.[18] On 30 June 1783 Fitzwilliam gave his maiden speech, giving the government's objections to the Shelburnite MP William Pitt's Bill to reform abuses in public offices. Horace Walpole recorded on 11 October that he did not know Fitzwilliam personally but that "from what I have heard of him in the Lords, I have conceived a good opinion of his sense; of his character I never heard any ill, which is a great testimonial in his favour, when there are so many horrid characters, and when all that are conspicuous have their minutest actions tortured to depose against them".[19]

Fitzwilliam was to have become head of the India Board under the Ministry's ill-fated India Bill.[20] Fitzwilliam was reported to have said in his speech on 17 December 1783 that "his mind, filled and actuated by the motives of Whiggism, would ill brook to see a dark and secret influence exerting itself against the independence of Parliament, and the authority of Ministers".[21] The failure of the Bill led to the fall of the Ministry and the appointment of Pitt as prime minister, with Fitzwilliam finding himself in opposition. On 27 December Fitzwilliam wrote to Dr Henry Zouch against parliamentary reform and that the cause of the present discontents was:

...not the corruption, not the lack of independence, not the want of patriotism in the House of Commons, but the unwise and desperate exercise of the royal prerogative to choose its own Ministers, by the dismission of those who have the confidence of the people, and the appointment of those who have it not. ...[Pitt was] a young man whose ambition is so restless, and boundless, that nothing will satisfy him but being first: while to gain the object of his passion, he cares little by what road he reaches it, and meanly submits to creep up the backstairs of secret influence. ... At this crisis, nothing should divert the public from this single object, a good government—till that is again obtained all must be confusion and distraction in the country: nothing can make it again, but the return of the old Ministers to the government of the country...any other object, diverting us from that, is at this moment ill timed, though it may be good abstractly.[22]

Fitzwilliam led the debate for the Whigs in the Lords on 4 February 1784. He attacked Pitt:

...his youth, his inexperience, his prediliction for court, and seclusion from those social circles where his equals of rank and fortune and years commonly resorted, were facts which always would have their weight in this country. ... Where were the great or meritorious things he had yet done, for which he had been so highly and strangely praised? ... what mighty schemes of public utility do the public owe to his industry, his abilities, and his invention?[23]

However, in the general election Pitt won a large majority. Fitzwilliam repudiated Lord Shelburne's attempt to get him the office of Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire. As he wrote to Lady Fitzwilliam on 4 September: "Having experienced very closely and very attentively his Lordship's conduct of late, and consequently having formed an opinion of his present principles, I can see no reason to expect that as an honest man I shall ever be able to give support to his administration, and therefore as a fair one I must decline receiving any favour at his hands".[24] Fitzwilliam was now considered the Duke of Portland's deputy, and was a key figure in Whig councils and was frequently the first Whig speaker in parliamentary debates.[25] On 18 July he attacked Pitt's trade policies with Ireland as "a system that overturned the whole policy of the navigation and trade of Great Britain", satisfying neither Britain nor Ireland. He said he spoke "as an Englishman" when he criticised the opening up of British and colonial markets to Ireland as detrimental to Britain and "as an Irishman" when he criticised the considerable burdens Ireland would be placed under. Ireland's grievances were constitutional, not economic, and he cited the government's plan to prevent public meetings.[26] Fitzwilliam was chosen to open the debate on the address at the opening of the next session of Parliament in 1786, and said that "The wisdom of Ireland had accomplished what the prudence of this country could not achieve".[27] In 1787 Fitzwilliam spoke only once, in opposition to trade with Portugal as this would be detrimental to Yorkshire manufacturers.[28]

In 1785 Fitzwilliam had been depicted in a magnificent portrait in oils by the leading painter of the day, Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy, an engraving of which, by Joseph Grozer dated 1786, is shown here. The portrait, with its turbulent sky, alludes to both the emotional turmoil the Earl had relatively recently suffered on the death of his uncle, Rockingham, and the political turmoil in which he had become embroiled following the dismissal of Fox and North from government at the end of 1783. Set in a landscape background, it also alludes to Fitzwilliam's wider responsibilities, which extended beyond the Parliamentary debating chamber.[29] As Ernest Smith has perceptively noted, 'Fitzwilliam grew up to be the typical eighteenth-century aristocrat – a man to whom politics was a natural responsibility due to his order, his family and his country, but not a field for the display of ambition. He was always fonder of the country than the town, of the local rather than the national arena. He saw his role throughout his life as that of leader of his local society and a link between the party and the public...Fitzwilliam's world...was that of the great estate owner.... Agents, tenantry, mortgages, leases and properties were his daily concern, and to these his life had in some measure to be dedicated.'[30] The portrait of Fitzwilliam by Reynolds had been missing since 1920 and was rediscovered in 2011.[31]

On 8 April 1788 Fitzwilliam wrote to Zouch on the Whigs' impeachment of Warren Hastings for his rule in India: "...disgraced, degraded, run down as they were, scarcely suffered to speak in the infancy of the present Parliament, this very Parliament has already conferred on them the distinguished duty of vindicating the justice of the nation, and of rescuing the name of Englishmen from the obloquy of tyranny over the inoffensive and the impotent".[32]

The Regency Crisis of 1788–89 led to an outbreak of support for Pitt in Yorkshire in the aftermath of Fox's assertion that the Prince of Wales had as much right to the throne during the King's illness as if he had inherited it. Zouch countered Fitzwilliam's proposal for a popular address in favour of the Prince of Wales' hereditary right: "[it would be a] very hazardous experiment".[33] Fitzwilliam opened the debate in the Lords on 15 December 1788, claiming that the Prince's right was "a question which...could not be brought under discussion without producing effects which every well-meaning and considerate individual must wish to avoid".[34] In January 1789 when the Commons' resolutions in favour of a Regency Bill (which would restrict the Prince of Wales' regal authority) came up to the Lords, Fitzwilliam said they would "reduce the constitution from the principles of a limited monarchy, and change it to the principles of a republic". He criticised Lord Camden's proposal that the Regent could create new peers only if the two Houses of Parliament consented: "[This was] in the highest degree unconstitutional, and he should, in consequence, think it his indispensable duty to come forward with a declaration condemning all such doctrines as repugnant to the principles of the British constitution".[35] If the Duke of Portland had formed an administration upon the Prince of Wales becoming Regent, Fitzwilliam would have been First Lord of the Admiralty, although Fitzwilliam was relieved when the King recovered from his illness and prospects of assuming this office subsequently disappeared.[36]

The Prince of Wales and the Duke of York toured the North of England in late 1789, and on 31 August they went to the race course at York and went in Fitzwilliam's carriage to enter the City of York, which was carried by the crowd rather than horses. On 2 September they were received by Fitzwilliam at Wentworth House for a lavish party, with 40,000 people enjoying a festival in the estate.[37] The Oracle described it thus: "It was in the true style of ancient English hospitality. His gates...were thrown open to the loyalty and love of the surrounding country. ... The diversions, consisting of all the rural sports in use in that part of the kingdom, lasted the whole day; and the prince, with the nobility and gentry, who were the noble earl's guests, participated in the merriment". The Annual Register said the ball was "the most brilliant ever seen beyond the Humber".[38] In the general election of 1790 Fitzwilliam contributed £20,000 to the Whigs' general election subscription and subsequently, the Whigs in Yorkshire enjoyed a recovery.[39]

Disintegration of the Whig party (1790–1794)

[edit]

In the dispute within the Whig party over the French Revolution, Fitzwilliam agreed with Edmund Burke over Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan but did not wish to split the party or endanger his friendship with Fox, the party's leader in the Commons.[40] Burke's son Richard had lately been appointed Fitzwilliam's London agent. When Richard Burke wrote to Fitzwilliam on 29 July 1790 to persuade him to turn Fox against Sheridan (who had split from Edmund Burke in February), Fitzwilliam replied on 8 August that he agreed that "the propriety of entering a caveat against the enthusiasm, or the ambition of any man whatever leading us into the trammels of Dr Price, Parson Horne, or any reverend or irreverend speculator in politics" but Fitzwilliam's letter to Fox did not change his behaviour.[41] Fitzwilliam did not praise Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France in public when it was published on 1 November 1790, although Burke claimed on 29 November that Fitzwilliam had acclaimed it.[42] Fitzwilliam wrote to his wife (in an undated letter) that the Reflections was "almost universally admired and approved".[43]

Fitzwilliam wrote to William Weddell on 2 March 1790 that he supported Fox's support for the repeal of the Test Act (which excluded Dissenters from power). When his friend Zouch campaigned against repeal Fitzwilliam wrote to him on 28 April 1791 that repeal could only be opposed on "an undeviating adherence to that which is—a principle to which I feel a strong attachment in most cases, because alteration and innovation is so seldom proposed to me, without a great alloy of experiment and uncertainty" but that Dissenters circumvented the Act and thus in practice the Church of England gained nothing from it but the Dissenters' hostility. Also, the Dissenters' leaders (Price, Priestley) would lose their influence by the removal of the Dissenters' main grievance.[44]

On 27 March 1791 Pitt mobilised the navy and sent an ultimatum to Russia to evacuate the Ochakov base it had occupied in its war against the Ottoman Empire. Fitzwilliam made the opening speech in the Lords on 29 March against the government. He objected on constitutional grounds giving the government discretionary power to augment the armed forces without fully laying out the circumstances, and that war with Russia would be "unjust, impolitic and in every way detrimental to the interests of this country".[45] The crisis nearly split up Pitt's government and he had made plans for a coalition with moderate Whigs (with Fitzwilliam or Viscount Stormont as Lord President of the council).[46]

Burke broke with Fox in a debate in the commons on 6 May 1791 over the French Revolution. Later that month Fitzwilliam offered financial assistance to Burke, who sat for one of his pocket boroughs, Malton in Yorkshire. Burke replied on 5 June, declaring that he would quit his seat before the session ended and that "I beg to appeal to your Equity and candour, whether I could receive any further Obligations of any kind out of a party whose publick principles are the very reverse of mine...let me beg the continuance of your private friendship and partial goodness—and believe there is not living one who more respects your Virtues publick and private, or that loves you with a more warm true and grateful attachment than I do".[47] Burke would refuse money from Fitzwilliam again on 21 November.[48] Fitzwilliam continued his friendship with Fox but his opinions were moving more in Burke's direction. French Laurence wrote to Burke on 8 August, claiming that Fitzwilliam had praised the Reflections "in a large, mixed company [and]...in a manner which made it understood to be his wish that his opinion should be as publicly known as possible".[49] Upon reading Burke's An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, he wrote to him on 18 September:

I thank you heartily for the pamphlet, and for the authorities you give me for the doctrines I have sworn by, long and long since: I know not how long, they have been my creed: I believe, before even my happiness in your acquaintance and friendship, tho' they have certainly been strengthen'd and confirm'd by your conversation and instruction—in support of these principles I trust I shall ever act, and I shall continue to attempt their general propagation;—whether by the best means, is matter of speculation: but by the best, according to my judgement—nothing can make me a disciple of Paine or Priestley, nor any thing induce me to proclaim, that I am not so, but in the mode I myself think the best to resist their mischief—private conversation and private insinuation may best suit the extent of my abilities, the turn of my temper, and the nature of my character...[50]

1792 saw Jacobinism gaining support in Sheffield and in late December an anonymous correspondent informed Fitzwilliam's friend Zouch of the increasing number "of the lower classes of manufacturers" professing "to be admirers of the dangerous doctrine of Mr Payne, whose pamphlet they distribute with industry and support his dogmas with zeal". Fitzwilliam was informed of a supposed plan to march on Wentworth House and destroy it as a symbol of privilege and oppression. Fitzwilliam advised his steward to construct defences for the house.[51] On 15 March 1792 Fitzwilliam and Fox had a long meeting in which they discussed the state of the Whig party. Fitzwilliam spoke of his fear about the spread of Jacobinism amongst the people. The next day Fox wrote to him:

Our apprehensions are raised by very different objects. You seem to dread the prevalence of Paine's opinions (which in most parts I detest as much as you do) while I am much more afraid of the total annihilation of all principles of liberty and resistance, an event which I am sure you would be as sorry to see as I. We both hate the two extremes equally, but we differ in opinions with respect to the quarter from which the danger is most pressing.[52]

One week after this conversation, Fitzwilliam hosted a dinner at which Burke was present. He and Burke twice talked privately, with Fitzwilliam urging Burke to reconcile with Fox, "or at least some steps towards it". As Burke wrote to his son Richard on 20 March: "I gave him such reasons why it could not be, yet at least, as made him not condemn me, though he left me, after our last conversation, in a mood sufficiently melancholy. He is, in truth, a man of wonderful honour, good nature and integrity".[53] On 11 April the Society of the Friends of the People was founded, which called for parliamentary reform. Fitzwilliam wrote to Zouch on 5 June that the reform societies in London, Sheffield, Manchester and Norwich were:

...hitherto contemptible, but they took a very different aspect when they were headed by a new Association, formed by some of the first men in the kingdom in point of rank, ability and activity—when members of Parliament began to tell the lowest orders of the people that they had rights of which they were bereaved by others; that to recover these rights they had only to collect together, and to unite; that if they were anxious to vindicate those rights they had the power of doing so, and to effect this, advocates and leaders were ready at their call. ... Now there is nothing but revolutions, and in that of France is an example of the turbulent and the factious instigating the numbers...to the subversion of the first principle of civil society...the protection of the individual against the multitude. ... The French revolutionists are just as anxious to bring into England their spirit of proselytism as they have been to carry it into every other part of Europe.[54]

In May 1792 Pitt sounded out the Portland Whigs, of which Fitzwilliam was one, for a possible coalition government. Fitzwilliam, with Fox, advised against it due to the insignificance of the posts offered.[55] On 9 June Fitzwilliam attended a meeting of leading Whigs at Burlington House. Burke condemned Fox and called for a coalition government. Fitzwilliam replied that he had "read an account of what had passed in the Association at Sheffield, and the resolution it had come to—a letter of thanks to its chairman, and of approbation from Grey—Lord Fitzwilliam alarmed, expressed a strong wish for government being supported in all measures which tended to strengthen the country".[56] Lord Malmesbury recorded:

When I was left alone with the Duke of Portland and Lord Fitzwilliam, we entered more deeply and more confidentially into the business. They agreed Fox's conduct had been very ill-judged, and very distressing: that to separate from him would be highly disagreeable, yet that to remain with him after what he professed, was giving their tacit approbation to the sentiments he had avowed in the House of Commons, on the Parliamentary Reform, which sentiments were in direct contradiction to theirs.[57]

On 18 June Lord Malmesbury recorded:

With Lord Fitzwilliam, in Grosvenor Square, for the purpose of discussing the subject of a coalition with him, and of endeavouring to prevail on him to speak to Fox—Lord Fitzwilliam's sentiments perfectly right—he said his opposition never had been to the constitution of the country, but to the Government when it acted in a way he thought contrary to the constitution; that, therefore, when that was in danger he ceased to be in opposition. On going over the matter it became evident that the great obstacle would arise from Fox's being too much entangled with Grey, Lambton, and that set of men who had lately separated themselves from the party, in order to form a party of their own, and who publicly professed doctrines and opinions in direct opposition to what he and I considered to be for the good and welfare of the public. That this would indeed be very hard and unreasonable, that for the sake of these very men, who both in their public and private capacity had been as inimical as possible, an arrangement should be broken off so salutary and so advisable. Lord Fitzwilliani and myself agreed on every point; he, however, went beyond me in insisting on the indispensable necessity of Pitt resigning the Treasury for another Cabinet office. He acquiesced in the wisdom of trying to bring Fox to be less attached to these false friends, and said Tom Grenville was the best man to speak to him. Lord Fitzwilliam expressed his dislike to Sheridan, said he might have a lucrative place, but never could be admitted to one of trust and confidence. On my wishing him not to leave town, he said he could safely trust his conscience with the Duke of Portland, and was at the same time ready to return at the shortest notice.[58]

At the end of August 1792 Richard Burke spoke with Fitzwilliam, who was hesitant about a coalition government, and said of Fox:

He said that he would safely and conscientiously trust him with a considerable trust in government, but I think he said it with a little hesitation. It is clear that he is not quite at ease about him, tho' as far as I can see determined not to abandon him. ... The combat in his mind between the candid interpretation of his friend's actions, and his own conviction deprives him of half the benefit of his understanding.[59]

After the news reached Fitzwilliam of the September Massacres in Paris, he hoped Fox would now join his old friends in the Whig party in condemning the violence of the French Revolution.[60] He attended the races at Doncaster that month, which enabled him to sound out county opinion. He wrote to Edmund Burke on 27 September that the French "cause is now looked upon with execration, and the fallacy of their system as universally admitted, as the wickedness and cruelty of their proceedings abominated. You will recollect the change of sentiment in the public upon the subject of the American war: on this occasion, the vane has veered not only more suddenly, but more completely too".[61] Lord Carlisle wrote to Fitzwilliam about the concern he felt about the state of the Whig party. Fitzwilliam replied on 31 October that the Friends of the People real aim was to split the Whig party:

They are certainly not unimportant men: and perhaps it may appear desirable that such men should not be irretrievably driven into the hands of the professed levellers. ... Putting aside all personal predilection in his favour, all affection and friendship...is he [Fox] to be shaken off from his connection with sound constitutional men, and forced into the arms of the Tookes and the Paines? We must be sure that the Colossus is theirs before we take a step to make him so. ... I am one of those who feel that one country has a self-interest in the events of another, and therefore for its own sake it is entitled to watch over them. ... France ought to be watched, not altogether on account of the spirit of universal interference and conquest which she manifests but on account of the weapons she uses...; it is not the red-hot balls of her cannon that are to be dreaded, but the red-hot principles with which she charges them. An invasion from these is what you and I dread, and if we feel that an universal junction is necessary in order to repel them, the foundation of that junction must be founded in exclusion.[62]

He also regretted Burke's attacks on Fox and Pitt's objection to Fox in a possible coalition government. In the aftermath of the Battle of Valmy (20 September) and the retreat of the counter-revolutionary armies, Burke and other conservative Whigs claimed that the Whigs must now be explicitly anti-French, even to the point of war. In late November Thomas Grenville wrote to Fitzwilliam and said that he spoke of "giving greater latitude to the principle of interference in internal governments of foreign countries, than I am prepared to give".[63] When France announced that King Louis XVI was to be put on trial, Pitt recalled Parliament by calling out the militia, an action Fitzwilliam thought unwarranted and designed to curry favour with conservative Whigs. He also viewed Fox's toasts to the rights of people as the only legitimate form of government as provocative at that moment, writing on 6 December: "I by no means like him".[64] At a meeting of leading Whigs at Burlington House on 11 December, Fitzwilliam tried to conciliate Fox in his desire to oppose the government. On 15 December Fox advocated recognising the French Republic and Fitzwilliam resisted pressure from conservative Whig MPs to split from Fox, supporting the Duke of Portland's attempts to keep the party together. With the mass-resignation from the Whig Club of Burke and other conservative Whig MPs, Fitzwilliam wrote to Lady Rockingham on 28 February 1793 and spoke of the Whig party split into three factions: those who wholeheartedly support the Revolution; those who wholeheartedly condemn it, support the government and wish for a war to destroy it; and the third (which Fitzwilliam identified with) "thinking French principles...wicked and formidable, are ready to resist them" by supporting the government's "measures of vigour" but "engaging for nothing further". The Friends of the People were responsible for the split, Fitzwilliam contended.[65]

When William Adam MP asked Fitzwilliam for money, he replied on 2 August that he would not pay a farthing to newspapers which propagated republicanism: "I trust I was always found as ready to make my proportionable deposits for services done as any of my associates, but the party was broke up a year and a half ago" and "from that period...I must be understood...as free from all demands for existing or future services".[66] When Adam suggested that Fitzwilliam could join with Fox in condemning the conduct of the war (which Britain had joined in February 1793), Fitzwilliam replied on 15 November: "I never will act in party with men who call in 4,000 weavers to dictate political measures to the government—nor with men whose opposition is laid against the constitution more than against the Ministers...[I support the] interference for the purpose of settling the internal government. ... France must start again from her ancient monarchy, and improving upon that is her only chance of establishing a system that will give happiness to herself, and ensure peace and security to her neighbours". The only hope for the party was "a completely successful termination of the present war" because it was this and not parliamentary reform which divided the party. However, when a public subscription was founded to settle Fox's debts (over £60,000), Fitzwilliam contributed a considerable amount.[67] In declining Richard Burke's request for a seat in Parliament, Fitzwilliam wrote to him on 27 August:

..why are you so cruel as to wring from me, as to force me to commit to paper, what I hardly confided to my own bosom, that he [Edmund Burke] and I materially differ in politics? I may give an occasional support to Mr Pitt...; I do and mean to give such support to the measure of the present war, to its propriety, its necessity, its justice...; but systematically I continue to be, and am, in opposition to him and his Ministry: there exists many a knotty point to be adjusted between him and me, many difficulties very important in their nature to be smoothed, much obliteration of facts not easy to be affected, and the general face of things strangely to be altered, before I retire from my watch upon his Ministry. ... [Burke has] delivered himself over into the hands of Pitt, formally and professedly, last November. ... He became the standard-bearer of his empire. ... He possessed in as full and ample a degree as ever my respect, my attachment, my affection, my veneration for his virtues, but in this instance he has failed to carry my conviction. ... We differ upon a fundamental point in politics.[68]

Edmund Burke was deeply upset by this letter and brought forth from Burke a "severe remonstrance" to Fitzwilliam "which affected Lord Fitzwilliam so much that he kept to his bed, and was actually ill for several days. When Burke heard this he was so much hurt in his turn, that he went to Lord Fitzwilliam and the whole thing was made up".[69] However Burke still felt unable to receive money from Fitzwilliam, declining it on 29 November.[70] Fox wrote to William Adam on 15 December that Fitzwilliam's "unremitting kindness to me in all situations quite oppresses me when I think of it. God knows, there is nothing on earth consistent with principle and honour that I would not do to continue his political friend, as I shall always be his warmest and most attached private friend".[71]

On 25 September the Duke of Portland met Pitt and was persuaded that Pitt would accept his terms for a coalition government: however Fitzwilliam convinced him that a coalition could only happen if the Whigs' were equal members and that Pitt must not be prime minister.[72] Fitzwilliam declared in a letter to Grenville on 7 November that Pitt's unwillingness to come out in support of a restoration of the House of Bourbon as the aim of the war was the main reason why he did not support Pitt.[73] On 25 December news arrived of the fall of British-occupied Toulon to the French revolutionary forces. The Duke of Portland immediately wrote to Fitzwilliam to inform him that he would visit Fox and tell him he would "support the war with all the effect and energy in my power" and end all ties to the Friends of the People. Fitzwilliam now declared "to take a more decided line than they had hitherto done, in support of the administration".[74] At the meeting of leading Whigs at Burlington House on 20 January 1794, the Duke of Portland delivered a blunt speech in which he supported the government and urged other Whigs to do the same. Fox believed this separated him from the leadership of the party and was the beginning of a future coalition government.[74]

On 17 February Fitzwilliam spoke against the Marquess of Lansdowne's peace motion:

...with regard to peace with France, we could have no hopes of it under the present system, unless we were prepared to sacrifice everything that was dear to us. ...His Lordship contended that the safety of the country, the preservation of the constitution, of everything dear to Englishmen and to their posterity depended upon the preventing the introduction of French principles, and the new-fangled doctrine of the rights of man; and that this could only be effected by the establishment of some regular form of government in that country upon which some reliance might be placed.[75]

In opposition to the peace motion introduced in the Commons by Fox and in the Lords by the Duke of Bedford on 30 May, Fitzwilliam said:

It had been urged that we had no right to interfere in the conduct of France. He denied the position. It became a great and magnanimous people to become the defenders of mankind. It had been the glorious province of England at all times. Our great King William had, in the same manner, risen up the defender of mankind against the ambition of Louis XIV. ... We had now the same object. ... We had a right to interfere in the internal affairs of France, until those internal affairs should be so regulated as to give security to mankind. He should withdraw his feeble support from Ministers if they were to abandon this principle. Nor had he any hesitation in declaring that he was an advocate for the re-establishment of monarchy in France, because that was an intelligent means of restoring order. It was not from his mere love of monarchy that he did this, but it was because he wished to have something solid to repose upon for the peace and happiness of mankind.[75]

He further declared his support for the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1794 and said that this "and other Acts were in unison with the opinion of the country".[75]

Formation of the Pitt–Portland coalition (May–July 1794)

[edit]

Throughout June the Portland Whigs were very close to forming a coalition government and it was the Duke of Portland's need to win Fitzwilliam's support for such a policy that alone stopped him taking the decision.[76] Fitzwilliam met him at Burlington House on 25 May in which he told Fitzwilliam he had met Pitt the previous day, with the Prime Minister telling him for his wish for a coalition as "the expulsion of that evil spirit [of Jacobinism]...and [said] that his wish and object was that it might make us act together as one great Family...[he] lamented the scantiness of Cabinet employments he had it in his power at this moment to offer us" but assured him that they would be offered when they became available. Fitzwilliam declined to meet Pitt with the Duke of Portland on 13 June as he was organising the Volunteers in the West Riding but his objection went deeper: "However frequently I have thought on the subject...it never occurs to me without presenting itself in some new point of view, which generally tends to render decision more difficult". He would not take that decision until Pitt clarified his offer of positions for Whigs in any prospective government.[77] The Duke of Portland claimed he could not further negotiate with Pitt without Fitzwilliam's support, with Fitzwilliam replying that without a declaration from Pitt that the main war aim was the restoration of the House of Bourbon he could not take office but he reassured him that if he joined the government he would have his support. Fitzwilliam also still thought the way Pitt had come to power in 1783 was "a severe blow to the spirit of the constitution and to Whiggism, which is the essence of it".[78]

On 18 June Pitt heard Fitzwilliam's objection from the Duke of Portland. Pitt assured, "that the re-establishment of the Crown of France in such person of the family of Bourbon as shall be naturally entitled to it was the first and determined aim of the present Ministry". Pitt wished to discuss this with Fitzwilliam in person.[79] On 23 June Fitzwilliam wrote to the Duke of Portland that he believed the government had moved to the Whig position and that "for my own part I am now ready, not only to adopt the opinion that a junction should take place, as your sentiment, but to advise it as the genuine offspring of my own judgement...[his only condition was that] as much weight and sway should be given to us as possible. ... In my humble opinion, this junction will not produce half its effect if it is not opened to the world by such marks of real substantial favour and confidence on the part of the Crown towards us as will mark beyond dispute the return of weight, power and consideration to the Old Whigs...after thirty years' exclusion from patronage in the line of peerage" new Whig peers should be created. He also rejected office except of "going to Ireland, but...it is impossible". However the Duke of Portland and Lord Mansfield implored Fitzwilliam to accept office and when Lord Mansfield saw Fitzwilliam when he came down to London on 28 June he got Fitzwilliam "to admit that if ever he was to take office this was the time".[80] The next day Fitzwilliam met the Duke of Portland and reported that: "I see little prospect of escaping office...the duke...seems so intent upon my accepting, as almost to say that he will not, if I do not—I left him last night my reasons for thinking that I should be more serviceable out of office, than in...if I find I have not persuaded him, I must submit". When Pitt met the Duke of Portland on 1 July he offered the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland to Fitzwilliam as soon as Lord Westmoreland could be compensated for the loss of it. Therefore, on 3 July Fitzwilliam agreed to join the coalition government as Lord President of the Council for the time being, writing that day to Lady Rockingham: "It is a time when private affection must give way to public exigency".[81]

Fitzwilliam wrote on 11 July: "I do not receive this honour (if it is one) with much exultation; on the contrary with a heavy heart. I did not feel great comfort in finding myself at St James's surrounded by persons with whom I had been so many years in political hostility, and without those I can never think of being separated from, publicly or privately, without a pang".[82] Some days earlier Fox had written to Fitzwilliam:

Nothing ever can make me forget a friendship as old as my life and the man in the world to whom I feel myself in every view the most obliged. ... Whatever happens I never can forget, my dearest Fitz, that you are the friend in the world whom I most esteem, for whom I would sacrifice every thing that one man ought to sacrifice to another. I know that the properest conduct in such a situation would be to say nothing, nor to inquire any thing from any of my old friends, and so I shall do in regard to all others, but I feel you to be an exception with respect to me to all general rules, I am sure your friendship has been so. God bless you, my dear Fitz.[82]

On 18 August Fox wrote to his nephew Lord Holland:

I cannot forget that ever since I was a child Fitzwilliam has been, in all situations, my warmest and most affectionate friend, and the person in the world of whom decidedly I have the best opinion, and so in most respects I have still, but as a politician I cannot reconcile his conduct with what I (who have known him for more than five-and-thirty years) have always thought to be his character. I think they have all behaved very ill to me, and for most of them, who certainly owe much more to me than I do to them, I feel nothing but contempt, and do not trouble myself about them; but Fitzwilliam is an exception indeed.[83]

Burke, however, was very pleased. He wrote to Fitzwilliam on 21 June to give notice that he intended to resign his seat in the Commons.[84] Fitzwilliam offered Burke's seat of Malton to his son Richard, who accepted.

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1794–1795)

[edit]

Fitzwilliam believed the coalition was formed not to support Pitt but to destroy Jacobinism at home and abroad; that the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland alienated Catholics from British rule and might drive them into supporting Jacobinism and a French invasion of Ireland; the loss of Ireland in such an event would weaken British sea power and make possible an invasion of England. Fitzwilliam aimed to reconcile Catholics to British rule by delivering Catholic Emancipation and ending the Protestant Ascendancy.[85]

Fitzwilliam accepted the Lord Lieutenancy on 10 August. The Duke of Portland wrote to Fitzwilliam four days later to say he had told Ponsonby, an Irish Whig, of the appointment.[86] He wrote to Henry Grattan on 23 August: "The chief object of my attempts will be, to purify, as far as circumstances and prudence will permit, the principles of government, in the hopes of thereby restoring to it that tone and spirit which so happily prevailed formerly, and so much to the dignity as well as the benefit of the country". He said he could only do this if Grattan and the Ponsonbys assisted him.[87] On 8 October Fitzwilliam wrote to the Duke of Portland to inform him of rumours in Ireland that Lord Westmorland was to continue as Lord Lieutenant and that if he was not announced soon as Lord Lieutenant he would resign from the government. The Duke of Portland replied that Pitt "harped" on needing to find Lord Westmorland another office and that he did not want the Irish Chancellor Lord FitzGibbon removed, as some Whigs were calling for. Fitzwilliam in turn responded that he would not accept the office unless given a free hand in both men and measures; he would not "step into Lord Westmorland's old shoes—that I put on the old trappings, and submit to the old chains" and declared he would resign.[88]

On 15 November leading Whigs met Pitt and Lord Grenville to discuss the situation. No record was kept of this meeting except by Fitzwilliam, and by Lord Grenville in March 1795. According to Fitzwilliam, they decided that: "Roman Catholick [question] not to be brought forward by Government, that the discussion of the propriety may be left open". Fitzwilliam claimed this meant that whilst the administration would not put forward Emancipation, they would not obstruct it should it pass the Irish Parliament. Lord Grenville however interpreted the meeting as deciding that Fitzwilliam "should, as much as possible, endeavour to prevent the agitation of the question during the present session; and that, in all events, he should do nothing in it which might commit the king's government here or in Ireland without fresh instructions from hence".[89] On 18 November Fitzwilliam wrote to Burke to reassure him: "the business is settled: that I go to Ireland—though not exactly upon the terms I had originally thought of, and I mean particularly in the removal of the Chancellor, who is now to remain, Grattan and the Ponsonbys desire me to accept: I left the decision to them".[90]

Fitzwilliam arrived in Balbriggan, Ireland on 4 January 1795. On 10 January he wrote to the Duke of Portland that "not one day has passed since my arrival without intelligence being received of violences committed in Westmeath, Meath, Longford and Cavan: Defenderism is there in its greatest force...I find the texture of government very weak" and chaotic. On 15 January he again wrote, claiming that the violence committed by peasants was not political but "merely the outrages of banditti" which could be solved by helping Catholics of rank to preserve law and order. This could only be done by Emancipation: "No time is to be lost, the business will presently be at hand, and the first step I take is of infinite importance". However he "endeavoured to keep clear of any engagement whatever" on Emancipation but that "there is nothing in my answer that they can construe into a rejection of what they are all looking forward to, the repeal of the remaining restrictive and penal laws":

I shall not do my duty if I do not distinctly state it as my opinion that not to grant cheerfully on the part of government all the Catholics wish will not only be exceedingly impolitick, but perhaps dangerous. ... If I receive no very peremptory directions to the contrary, I shall acquiesce with a good grace, in order to avoid the manifest ill effect of a doubt or the appearance of hesitation; for in my opinion even the appearance of hesitation may be mischievous to a degree beyond all calculation.[91]

On 6 January he offered the Primacy of Ireland to the Bishop of Waterford and Lismore and Thomas Lewis O'Beirne the Bishopric of Ossory. He also offered Richard Murray the post of Provost of Trinity College Dublin and George Ponsonby the Attorney-Generalship in place of Arthur Wolfe (who would be Chief Justice). The Duke of Portland consented to all these.[92] On 9 January Fitzwilliam informed John Beresford, First Commissioner of the Revenue and the leading supporter of Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, that he was relieved of office with a pension of the same amount as his salary. On 10 January Fitzwilliam relieved John Toler of the Solicitor-Generalship and promised him the first vacant seat on the judicial bench and his wife was to be made a peer.[93] On 2 February the Duke of Portland protested at Ponsonby's promotion and Wolfe as Chief Justice. On 5 February Fitzwilliam wrote to Pitt: "I have every reason to expect a great degree of unanimity in support of my administration: nothing can defeat those expectations unless an idea should go forth that I do not possess the fullest confidence, and cannot command the most cordial support of the British Cabinet".[94] On reading this the King claimed emancipation would mean "the total change of the principles of government which have been followed by every administration in that kingdom since the abdication of James II...[it is] beyond the decision of any Cabinet of Ministers". Fitzwilliam was "venturing to condemn the labours of ages...[which] every friend to the Protestant religion must feel diametrically contrary to those he has imbibed from his earliest youth".[95] On 7 February the Cabinet decided that Fitzwilliam must postpone as much as possible an Emancipation Bill.[96] Writing on 10 February to the Duke of Portland, Fitzwilliam said Emancipation would have a good effect on the spirit and loyalty of the Catholics of Ireland, and Catholics of rank would be reconciled to British rule and put down disturbances. He also proposed a native yeomanry officered by Catholic gentry which would enable the British Army garrison to leave be used against the French.[97] Two days after, Grattan requested in the Irish House of Commons permission to introduce a Roman Catholic Relief Bill.

Beresford and other Irish supporters of Ascendancy were alarmed at Fitzwilliam's policies. Pitt wrote to Fitzwilliam on 9 February that Beresford's removal was never "to my recollection...hinted at even in the most distant manner...much less...without his consent" and that he should have discussed it at the meeting held on 15 November. Furthermore, Fitzwilliam's policies were "in contradiction to the ideas which I thought were fully understood among us. ... On most of these points I should have written to your lordship sooner but the state of public business has really not left me the time of doing so; and it is not without very deep regret that I feel myself under the necessity of interrupting your attention by considerations of this sort while there are so many others of a different nature which all our minds ought to be directed".[98] On 14 February Fitzwilliam replied that it was to support national security that he made those appointments: the disaffection amongst Catholics was great and so a change in direction was needed to retain Ireland. His fears of Beresford's "power and influence" had been "too well founded: I found them incompatible with mine...and after the receipt of this, you will be prepared to decide between Mr Beresford and me and that the matter is come to this issue is well known here". Fitzwilliam asserted that he had already informed Pitt of his intention to remove Beresford and he had "made no objection, nor, indeed, any reply", which he took to mean the decision was at his discretion. If Pitt refused his advice, he should be recalled: "These are not times for the fate of the empire to be trifled with. ... I will deliver over the country in the best state I can to any person, who possesses more of your confidence".[99]

The Duke of Portland wrote to Fitzwilliam on 16 February, in a letter approved by the Cabinet, that the Bill would "produce such a change in the present constitution of the House of Commons as will overturn that, and with it the present ecclesiastical establishment". In his private covering letter of 18 February to this letter, he spoke of being "too much hurt and grieved" by Fitzwilliam's ultimatum and begged him to be patient. Two days after he sent the Cabinet's demand that they "inform you in the plainest and most direct terms that we rely upon your zeal and influence to take the most effectual means in your power to prevent any further proceeding being had on that Bill until his Majesty's pleasure shall be signified to you with regard to your future conduct respecting it". The next day the Cabinet met and the Duke of Portland advised that Fitzwilliam be recalled. He wrote to Fitzwilliam on 20 February that recalling him:

...was the most painful task I ever undertook; [but it was] my opinion, and I call it mine, because I chose to be the first to give it, and I was, I believe, the only member of the Cabinet who gave it decidedly, that the true interest of government...requires that you should not continue to administer that of Ireland. ... There appears such a concurrence in the views, such a deference to the suggestions and wishes, and such an acquiescence in the prejudices of Grattan and the Ponsonbys that there seems to me no other way of rescuing you and English government from the annihilation which is impending over it. ...the inordinate desire of George Ponsonby [is your downfall]. Do you feel that the government of Ireland is really in your hands? ... Let me implore you to make it your own desire to come away from Ireland. ... I write to you in the agony of my soul, impelled by the sense of my friendship and attachment to you and of my duty to the public.[100]

The official letter recalling Fitzwilliam was sent on 23 February, with private letters by the Duke of Portland, Lord Mansfield, Lord Spencer, William Windham and Thomas Grenville all begging him to accept the King's wish that he should resume his old seat in the Cabinet (which Fitzwilliam rejected). The Duke of Portland wrote:

If any injury has been done to you, if any blow has been aimed at your political character and reputation, it is I who have attempted it; revenge yourself on me, renounce me, but assist in saving your country—I will retire, I will make any extirpation or atonement that can satisfy you—you are younger, more active, more able than I am, you can do more good. If my...renunciation of the world will restore you to the public service, God forbid I should hesitate a moment.[100]

Fitzwilliam wrote to the Duke of Devonshire on 28 February that his recall:

...is a subject of the greatest pain and mortification to me, because it must be the cause of the most complete separation between the Duke of Portland and myself. Either I have been the most wild, rash, unfaithful servant to the Crown and to England, or he has abandoned in the most shameful manner his friend, and his friend's character, for pursuing generally a system of measures that has been the perpetual theme of his conversation, and the subject of his recommendation for years back. It is painful, a trying task to submit to a separation from a man I have loved so long and so much; but I must submit to it, for I will not abandon my character to the disgraceful imputations that must attach upon it if I do not justify it by charging him with the most shameful dereliction of his friend that ever was experienced by a faithful and a tried one.[101]

On 6 March Fitzwilliam said in a letter to Lord Carlisle that it was his removal of Beresford and his friends for their "maladministration" and not Emancipation that was his downfall. Pitt was determined to use the Bill as an excuse to get rid of the Whig government in Ireland, spurred on by "secret, unavowed, insidious informations" and breaking the terms of the coalition agreed with the Duke of Portland. The claim that he had breached the agreement was merely the excuse needed to get rid of him due to the resentment by the Ascendancy at their loss of power. He instead claimed his administration had been a success, enjoying widespread popularity amongst the Irish and granted by the Irish House of Commons "the largest supplies that have ever been demanded". Fitzwilliam urged Lord Carlisle to show this to "as many persons as you shall think proper".[102] On 9 March Fitzwilliam said in a letter to James Adair: "Here I am, abandoned, deserted and given up—an object of the general calumny of administration, for they must abuse me to justify themselves".[101] After hearing reading in government newspapers that his recall was due to Emancipation, Fitzwilliam wrote to Lord Carlisle on 23 March and said that the Catholic question entered for nothing into the real cause of my recall" and that he acted within the bounds of the agreement decided on 15 November. He said repeated requests for instructions to the Cabinet on the bill had been ignored whilst they had responded almost at once to the dismissal of Beresford and his friends. The visit of Beresford to London and the prospect of a "change in system" in Ireland made the Cabinet recall him. The Duke of Portland had been seduced into altering "all his former opinions respecting the politics of this country" and he was now Pitt's instrument. Pitt had used the situation to abandon the coalition agreement with the Whigs that the Irish administration be under the Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland. Pitt had resumed control of it and handed it back to the corrupt Ascendancy.[103]

Fitzwilliam left Ireland on 25 March, the Dublin streets silent and decked in mourning. Grattan said although they were silent and unhappy there "Never was a time in which the opposition here were more completely backed by the nation, Protestant and Catholic united".[104] The two letters to Lord Carlisle were published in Dublin and then in London (without Fitzwilliam's knowledge) in a pirated and a somewhat altered state under the title A Letter from a Venerated Nobleman, recently retired from this country, to the Earl of Carlisle: explaining the causes of that event. The publication shocked many of Fitzwilliam's friends and brought forth their condemnation. Fitzwilliam was unrepentant, writing to Thomas Grenville on 3 April that the Duke of Portland "has been bewildered, and in his confusion has been led into irretrievable error; but that error is of a nature never, I fear, to be got over: he has been induced to abandon his principles, and give up his friend, his firm, his steady his staunch supporter. ... [He] suffered himself to be the dupe of cunning and design, has been made the instrument of his own and my disgrace—a disgrace of a nature most gratifying to our common enemies. [I am resolved] to separate myself altogether from every sort of intercourse with the man with whom I have passed so many years of my life in the most intimate, cordial, unsuspecting friendship".[105]

Fitzwilliam decided upon a memorial to be presented to the King defending his Lord Lieutenancy. It was drafted by Burke and shortened by Lord Milton. Burke wrote that "My Idea was to proceed not so much by way of a direct answer to a charge, though that too, obliquely, was not be neglected; as in the way of a charge on your Enemies, so as to put them upon their defence".[106] Fitzwilliam attended a levee on 22 April and had an audience with the King in the closet, where he presented his memorial. He wrote to Grattan on 25 April that at the levee "Very little was said to me; only a few questions about my son's health; however, I thought the manner gracious, as the King, upon seeing me, passed by some people to come directly to me". During the audience, Fitzwilliam explained his position and the King "Upon the whole his attention was gracious, but he gave no opinion whatever, only as to my intentions".[107] The King wrote to Pitt on 29 April that the memorial was "rather a panegyric on himself than any pointed attack on Ministry...I cannot say much information is to be obtained from it".[108]

On 24 April he spoke in the Lords to demand an investigation into his Lord Lieutenancy and the reasons why he was recalled, claiming that the government had attempted "to throw all the blame from their own shoulders, and...to fix the load on his". Lord Grenville replied that "the mere fact of a nobleman being removed from being Lord Lieutenant of Ireland" meant no censure of a personal nature, nor for any investigation. Lord Moira and the Duke of Norfolk supported Fitzwilliam and moved for a committee of inquiry. On 8 May the debate on this took place but the government claimed appointments and dismissals were the prerogatives of the King, although all sides declared their belief in Fitzwilliam's integrity. The motion got the support of only 25 votes. Fitzwilliam's protest he had wanted in the Journal of the House of Lords stated that he had "acted with an enlightened regard to the true interests of the nation" and that religious prejudices be dissolved "in one bond of common interest, and in one common effort against our common enemies, the known enemies of all religion, all law, all order, all property".[109]

Beresford wrote to Fitzwilliam on 22 June that his character had been unjustly attacked: "Direct and specific charges I could fairly have met and refuted, but crooked and undefined insinuations against private character, through the pretext of official discussion, your Lordship must allow, are the weapons of a libeller".[110] Fitzwilliam replied the next day that domestic matters took charge of his attention but on 28 June that he let Beresford know he was now in town and "As I could not misunderstand the object of your letter, I have only to signify that I am ready to attend your call".[111] Rumours of the impending duel leaked and Fitzwilliam was "obliged to quit the house...hastily in the morning, for fear of arrest by the police". His second, Lord George Cavendish, met Beresford's second (Sir George Montgomery) on 28 June and debated an apology by Fitzwilliam. His proposed apology was not acceptable to Beresford. Their first arena, Marylebone fields, was crowded with prospective spectators so they moved to a field near Paddington. As Beresford and Fitzwilliam were taking their marks a magistrate ran onto the field and arrested Fitzwilliam. Fitzwilliam said to Beresford "that we have been prevented from finishing this business in the manner I wished, I have no scruple to make an apology". Beresford accepted and they shook hands, with Fitzwilliam saying "Now, thank God, there is a complete end to my Irish administration" and hoped that "whenever they met it might be on the footing of friends".[112][113][114] Burke wrote to Lord John Cavendish on 1 July that "it is happy, that a Virtuous man has escaped with Life and honour—and that his reputation for spirit and humanity, and true dignity must stand higher than ever, if higher it could stand".[115]

Opposition (1795–1806)

[edit]Fitzwilliam was now in opposition to both the Pitt–Portland coalition government and the Foxites. He wrote to Adair on 13 September 1795: "I stand unconnected with any political party".[116] During the summer of 1794 he took a leading part in organising West Riding yeomanry cavalry against to put down popular protests that the establishment saw as Jacobin threats to law, order and property, and as colonel-commandant of these regiments he in person led them to put down disturbances in Rotherham and Sheffield in the summer of 1795.[116]

On 4 August 1795 in Sheffield, a newly raised regiment complained that their bounties were being withheld from them. A crowd assembled in their support and refused to disperse. The Riot Act was read and the local Volunteers fired on the crowd, killing two and injuring others. Fitzwilliam wrote to Burke on 9 August: "...the Volunteer corps have shewn their readiness to act in support of Law and Order, in a manner that must give great satisfaction to all those, who wish to see them maintain'd ... in the manner, in which it has ended, I trust it will be productive of good, and tend much to the future quiet of the place".[117] Fitzwilliam wrote on 6 October to George Ponsonby that the Foxites were supporting "the most desperate system of universal subversion" and could not be trusted: "With my disinclination to the Ministry,with the affections I shall ever bear to the most conspicuous part of Opposition, I must...agree with my neighbours in thinking that before Opposition can be Ministers they must give to the public, security...for the maintenance of things as they are".[118] On 8 December Pitt announced that the government was considering peace with the newly established Directory of France. The next day Burke wrote to Fitzwilliam: "You are to judge, whether you ought to come down and make your Protest against this shameful and ruinous Business. You will certainly stand alone. But this is not always to stand disgraceful".[119] Fitzwilliam gave his speech on 14 December, and said the war was "of a nature different from all common wars" and had commenced:

...not from any of the ordinary motives of policy and ambition in which wars generally originate. It was expressly undertaken...to restore order to France, and effect the destruction of the abominable system that prevailed in that country. Upon this understanding it was that he had separated from some of those with whom he had long acted in politics, and...upon this understanding he had filled that situation, which he some time since held in His Majesty's Cabinet. ... [France] was still a pure democracy, containing the seeds of dissension and anarchy and affording no security for religion, property or order.[120]

Burke wrote on 16 December: "I read with the greatest possible satisfaction some account of your Speech in the House of Lords".[119] Fitzwilliam replied to Burke's first letter on 17 December: "Your letter came most opportunely to decide a wavering mind to the thing that was right" and he said of the Seditious Meetings Act 1795:

I could not help thinking what a feeble and futile effort to keep down Jacobinism this bill must be, when compar'd with the effect to be produc'd by all the consequences arising from compromising with its existence under color of a peace with the Nation—what is to be done with all their Com[missioner]s Ambassadors, Consuls, and Citizens? Are they to range at large, in every town and every house, preaching their doctrines, and perhaps even buying proselytes?—are Englishmen to be sent to Paris to be witnesses of the successful result of audacious usurpation, and of the elevation of Tom Paine, from a Staymaker to a fine Gentleman, from an Exciseman to a Sovereign, as the reward of the Rights of Man and the Age of Reason—I fear Restriction and Coercion will avail little against the influence of example—but our Ministers have made up their minds, to save Jacobinism, at its last gasp, and the experiment of shaking hands with it...[121]

Fitzwilliam wrote to Adair on 12 September that he would support the government on the war and "on all occasions where they support establishment against innovation, monarchy and aristocracy against the inroads of sans-culottism; but beyond these points I profess no friendship or goodwill towards an administration from which I have received such gross ill-treatment". The Foxites were no better: "I don't know that they would wish for the appearance of connexion with me, and I am sure I should but little wish it with them, till such time as all the leaven of sans-cullotism is worked out of their composition".[122] He was now the pre-eminent spokesman for Burkean principles: he wrote to Burke on 30 August 1796 to offer the seat of Peterborough to Burke's friend French Laurence. Fitzwilliam said he was "the inveterate enemy of all innovation" and "though a friend to popular privileges on ordinary occasions, and having no dislike to the check on public men by popular discussion...I had rather see a bad Minister go uncorrected than a good constitution stabbed in its vitals". He further claimed:

...under no circumstances whatever will I be in connexion with Mr Pitt. It is sufficient for a man's life to have been duped once. I hesitate no less to say that I will never hold communication with the Duke of Portland until he has made that amende honorable to those...whose weight and consideration in Ireland he has made subservient to his own purposes and views in this country. ...my inclinations, my private attachments, the habits of my life, all combine to make me anxious to see the moment when I may be able to give the members of opposition honourable assistance. ... But in stating this it certainly is not in my contemplation to become again an active member of an opposition. Those days are over—circumstances have happened that make me think that I can be no more usefully so...but, in one word, should circumstances ever present to me the opportunity of doing essential injury to Mr Pitt's power, or of rendering effectual service to Mr Fox, I will not fail to seize it.[123]

When the new parliamentary session began on 6 October Fitzwilliam moved an amendment (drafted by Burke) to the address criticising Lord Malmesbury's peace mission to France, the only person to do so. This near-universal support was due "not from Opposition concurring in the measures of Government but from Government abandoning their own measures of to adopt those of Opposition—the regular order of things seems subverted". It was futile to desire peace with "a species of power, with whose very existence all fair and equitable accommodation is incompatible". Furthermore, such a peace would be dishonourable because the government had previously stated it would only seek peace "through the ancient and legitimate government long established in France" and that he solemnly recorded his discharging "of the duty I owe to my king and country".[124] The Annual Register said Fitzwilliam's protest "breathes the genuine spirit first roused, and perhaps, still actuated to a greater extent than was acknowledged by the British government".[124] Laurence wrote to Fitzwilliam on 26 October that Henry Addington, Speaker of the House of Commons, viewed him as "man of high integrity; no person could say that his lordship had abandoned his principles".[125] Burke wrote to Fitzwilliam on 30 October of his appreciation of "the solo you played in the grand orchestra" and that his arguments were "relished by the public" and were given greater power due to "your personal weight and character". Burke further stated that his Two Letters on a Regicide Peace were a "poor attempt to second what you have done".[126] Fitzwilliam wrote to Burke on 10 November that his pamphlets had "roused a spirit in the country, which does not act, only because those, who ought to make use of it, choose to keep it under". He also claimed that "It is the dread of a [French] expedition slipping over to Ireland, and erecting there the standard of revolt, which makes him [Pitt] drive England headlong into peace".[127] Fitzwilliam wrote to Laurence on 10 November that "Every other political consideration, continental connexions, balance of power in Europe—the existence of civil society itself—is to be sacrificed, rather than give up their system in Ireland. ... Had it been permitted to me to have gratified them [the Catholics] in the little they looked for, Ireland would not have been what it now is, a millstone upon the neck of England".[128]

On 30 December Fitzwilliam moved an amendment in the Lords in the debate on Lord Malmesbury's recall from France following his unsuccessful peace negotiations. It stated "the dangerous principles advanced by the French Republic, the necessity of a perseverance in the contest, and the impropriety of courting any negotiation of peace with France in its present state". Lord Grenville and Lord Spencer spoke out against it, however. Fitzwilliam agreed with Fox over the unconstitutional nature of Pitt's loan to Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, who did it without Parliament's consent. Writing to Laurence on 11 December, he said Pitt was guilty of "a proud, arrogant assumption of power, that...if it passes unnoticed, it is a dangerous infraction upon a most material constitutional principle and usage".[129]

Fitzwilliam wrote to Laurence on 22 February 1797 that he did not wish for a change in government lest it "lead to a change in the constitution" but agreed that a "reform in the abuses of executive government" was needed and that Fox would carry on the war "for the same reason [as the government], and peace would be made by him more to advantage, because, made by him, there would be virtually a saving of the country's honour—made by Mr Pitt, the country is beat into it' made by Mr Fox it is a measure of choice".[130] In March 1797 he looked with sympathy on a scheme by MPs and peers to form a government without Pitt and wrote a Memorial on the state of Ireland in which he called for Emancipation and the sacking of anti-Catholic members of the Irish government, which would reconcile Catholics to British rule and halt the spread of Jacobinism. He spoke in the Lords to put forward these proposals but it was rejected by 72 votes to 20.[131] Fitzwilliam wrote on 2 April that he was "the most isolated individual in politics in the king's dominions...a person who approves of nothing doing and therefore of no set of men whatever". The government had abandoned its principles and the Foxites were "more hostile in ten times in my opinion, and more decided to act upon principles contrary to my views, than the Ministry".[132] On 30 May Fitzwilliam met Burke at his home in Beaconsfield during his last illness before his death. Burke reported to Laurence that Fitzwilliam had "a strong predilection to Mr Fox" and "influenced, too much so in my opinion, though very naturally and very excusably, by a rooted animosity against Mr Pitt".[133] Fitzwilliam returned to his previous independence when the scheme for a "third party" collapsed and Laurence wrote to Fitzwilliam on 9 July (the day of Burke's death) that Burke had said on his deathbed: "Inform Lord Fitzwilliam from me that it is my dying advice and request to him, steadily to pursue that course in which he now is. He can take no other that will not be unworthy of him". Laurence said "this was almost if not quite the last thing which he said on public affairs".[134] Fitzwilliam wrote to Laurence on 11 July of Burke's death:

The loss is irreparable in every point of view: with him is gone all true philosophy, all publick virtue; there is nothing left but factious schemes and time-serving manoeuvres, contending one with the other, which shall do most mischief—not one English sentiment, not one statesmanlike idea—this is the publick loss. the private one is of everything that was warm, zealous, partial, where once he had placed his affections; for my own part, I feel it is the loss, not of a friend, but of a father; of one to whom I looked up for advice and instruction; and who gave them with the interest and fidelity of a parent.[135]

Writing on 25 January 1798 to a friend, Fitzwilliam claimed his objections to the Foxites stemmed not mainly because of their advocacy of peace with France but over their support for parliamentary reform, which "will truly frenchify us: for my part I have nothing less at heart than to be frenchified.[136] In February the King offered him the Lord Lieutenancy of the West Riding of Yorkshire after the Duke of Norfolk was relieved of it after his toast to "Our sovereign—the Majesty of the People". Fitzwilliam accepted on the condition that it was to be publicly known that the offer came from the King and not the government.[137]