Thales's theorem

In geometry, Thales's theorem states that if A, B, and C are distinct points on a circle where the line AC is a diameter, the angle ∠ ABC is a right angle. Thales's theorem is a special case of the inscribed angle theorem and is mentioned and proved as part of the 31st proposition in the third book of Euclid's Elements.[1] It is generally attributed to Thales of Miletus, but it is sometimes attributed to Pythagoras.

History

[edit]

Non si est dare primum motum esse

o se del mezzo cerchio far si puote

triangol sì c'un recto nonauesse.

– Dante's Paradiso, Canto 13, lines 100–102

Non si est dare primum motum esse,

Or if in semicircle can be made

Triangle so that it have no right angle.

– English translation by Longfellow

Babylonian mathematicians knew this for special cases before Greek mathematicians proved it.[2]

Thales of Miletus (early 6th century BC) is traditionally credited with proving the theorem; however, even by the 5th century BC there was nothing extant of Thales' writing, and inventions and ideas were attributed to men of wisdom such as Thales and Pythagoras by later doxographers based on hearsay and speculation.[3][4] Reference to Thales was made by Proclus (5th century AD), and by Diogenes Laërtius (3rd century AD) documenting Pamphila's (1st century AD) statement that Thales "was the first to inscribe in a circle a right-angle triangle".[5]

Thales was claimed to have traveled to Egypt and Babylonia, where he is supposed to have learned about geometry and astronomy and thence brought their knowledge to the Greeks, along the way inventing the concept of geometric proof and proving various geometric theorems. However, there is no direct evidence for any of these claims, and they were most likely invented speculative rationalizations. Modern scholars believe that Greek deductive geometry as found in Euclid's Elements was not developed until the 4th century BC, and any geometric knowledge Thales may have had would have been observational.[3][6]

The theorem appears in Book III of Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC) as proposition 31: "In a circle the angle in the semicircle is right, that in a greater segment less than a right angle, and that in a less segment greater than a right angle; further the angle of the greater segment is greater than a right angle, and the angle of the less segment is less than a right angle."

Dante Alighieri's Paradiso (canto 13, lines 101–102) refers to Thales's theorem in the course of a speech.

Proof

[edit]First proof

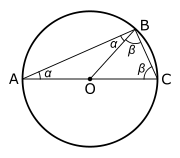

[edit]The following facts are used: the sum of the angles in a triangle is equal to 180° and the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal.

Since OA = OB = OC, △OBA and △OBC are isosceles triangles, and by the equality of the base angles of an isosceles triangle, ∠ OBC = ∠ OCB and ∠ OBA = ∠ OAB.

Let α = ∠ BAO and β = ∠ OBC. The three internal angles of the ∆ABC triangle are α, (α + β), and β. Since the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to 180°, we have

Second proof

[edit]The theorem may also be proven using trigonometry: Let O = (0, 0), A = (−1, 0), and C = (1, 0). Then B is a point on the unit circle (cos θ, sin θ). We will show that △ABC forms a right angle by proving that AB and BC are perpendicular — that is, the product of their slopes is equal to −1. We calculate the slopes for AB and BC:

Then we show that their product equals −1:

Note the use of the Pythagorean trigonometric identity

Third proof

[edit]

Let △ABC be a triangle in a circle where AB is a diameter in that circle. Then construct a new triangle △ABD by mirroring △ABC over the line AB and then mirroring it again over the line perpendicular to AB which goes through the center of the circle. Since lines AC and BD are parallel, likewise for AD and CB, the quadrilateral ACBD is a parallelogram. Since lines AB and CD, the diagonals of the parallelogram, are both diameters of the circle and therefore have equal length, the parallelogram must be a rectangle. All angles in a rectangle are right angles.

Converse

[edit]For any triangle, and, in particular, any right triangle, there is exactly one circle containing all three vertices of the triangle. (Sketch of proof. The locus of points equidistant from two given points is a straight line that is called the perpendicular bisector of the line segment connecting the points. The perpendicular bisectors of any two sides of a triangle intersect in exactly one point. This point must be equidistant from the vertices of the triangle.) This circle is called the circumcircle of the triangle.

One way of formulating Thales's theorem is: if the center of a triangle's circumcircle lies on the triangle then the triangle is right, and the center of its circumcircle lies on its hypotenuse.

The converse of Thales's theorem is then: the center of the circumcircle of a right triangle lies on its hypotenuse. (Equivalently, a right triangle's hypotenuse is a diameter of its circumcircle.)

Proof of the converse using geometry

[edit]

This proof consists of 'completing' the right triangle to form a rectangle and noticing that the center of that rectangle is equidistant from the vertices and so is the center of the circumscribing circle of the original triangle, it utilizes two facts:

- adjacent angles in a parallelogram are supplementary (add to 180°) and,

- the diagonals of a rectangle are equal and cross each other in their median point.

Let there be a right angle ∠ ABC, r a line parallel to BC passing by A, and s a line parallel to AB passing by C. Let D be the point of intersection of lines r and s. (It has not been proven that D lies on the circle.)

The quadrilateral ABCD forms a parallelogram by construction (as opposite sides are parallel). Since in a parallelogram adjacent angles are supplementary (add to 180°) and ∠ ABC is a right angle (90°) then angles ∠ BAD, ∠ BCD, ∠ ADC are also right (90°); consequently ABCD is a rectangle.

Let O be the point of intersection of the diagonals AC and BD. Then the point O, by the second fact above, is equidistant from A, B, and C. And so O is center of the circumscribing circle, and the hypotenuse of the triangle (AC) is a diameter of the circle.

Alternate proof of the converse using geometry

[edit]Given a right triangle ABC with hypotenuse AC, construct a circle Ω whose diameter is AC. Let O be the center of Ω. Let D be the intersection of Ω and the ray OB. By Thales's theorem, ∠ ADC is right. But then D must equal B. (If D lies inside △ABC, ∠ ADC would be obtuse, and if D lies outside △ABC, ∠ ADC would be acute.)

Proof of the converse using linear algebra

[edit]This proof utilizes two facts:

- two lines form a right angle if and only if the dot product of their directional vectors is zero, and

- the square of the length of a vector is given by the dot product of the vector with itself.

Let there be a right angle ∠ ABC and circle M with AC as a diameter. Let M's center lie on the origin, for easier calculation. Then we know

- A = −C, because the circle centered at the origin has AC as diameter, and

- (A – B) · (B – C) = 0, because ∠ ABC is a right angle.

It follows

This means that A and B are equidistant from the origin, i.e. from the center of M. Since A lies on M, so does B, and the circle M is therefore the triangle's circumcircle.

The above calculations in fact establish that both directions of Thales's theorem are valid in any inner product space.

Generalizations and related results

[edit]As stated above, Thales's theorem is a special case of the inscribed angle theorem (the proof of which is quite similar to the first proof of Thales's theorem given above):

- Given three points A, B and C on a circle with center O, the angle ∠ AOC is twice as large as the angle ∠ ABC.

A related result to Thales's theorem is the following:

- If AC is a diameter of a circle, then:

- If B is inside the circle, then ∠ ABC > 90°

- If B is on the circle, then ∠ ABC = 90°

- If B is outside the circle, then ∠ ABC < 90°.

Applications

[edit]Constructing a tangent to a circle passing through a point

[edit]

Thales's theorem can be used to construct the tangent to a given circle that passes through a given point. In the figure at right, given circle k with centre O and the point P outside k, bisect OP at H and draw the circle of radius OH with centre H. OP is a diameter of this circle, so the triangles connecting OP to the points T and T′ where the circles intersect are both right triangles.

Finding the centre of a circle

[edit]Thales's theorem can also be used to find the centre of a circle using an object with a right angle, such as a set square or rectangular sheet of paper larger than the circle.[7] The angle is placed anywhere on its circumference (figure 1). The intersections of the two sides with the circumference define a diameter (figure 2). Repeating this with a different set of intersections yields another diameter (figure 3). The centre is at the intersection of the diameters.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Heath, Thomas L. (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. Vol. 2 (Books 3–9) (2nd ed.). Dover. p. 61. ISBN 0486600890. Originally published by Cambridge University Press. 1st edition 1908, 2nd edition 1926.

- ^ de Laet, Siegfried J. (1996). History of Humanity: Scientific and Cultural Development. UNESCO, Volume 3, p. 14. ISBN 92-3-102812-X

- ^ a b Dicks, D. R. (1959). "Thales". The Classical Quarterly. 9 (2): 294–309. doi:10.1017/S0009838800041586.

- ^ Allen, G. Donald (2000). "Thales of Miletus" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ^ Patronis, Tasos; Patsopoulos, Dimitris (January 2006). "The Theorem of Thales: A Study of the Naming of Theorems in School Geometry Textbooks". The International Journal for the History of Mathematics Education: 57–68. ISSN 1932-8826. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Sidoli, Nathan (2018). "Greek mathematics" (PDF). In Jones, A.; Taub, L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Science: Vol. 1, Ancient Science. Cambridge University Press. pp. 345–373.

- ^ Resources for Teaching Mathematics: 14–16 Colin Foster

References

[edit]- Agricola, Ilka; Friedrich, Thomas (2008). Elementary Geometry. AMS. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8218-4347-5.

- Heath, T.L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics: From Thales to Euclid. Vol. I. Oxford. pp. 131ff.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Thales' Theorem". MathWorld.

- Munching on Inscribed Angles

- Thales's theorem explained, with interactive animation

- Demos of Thales's theorem by Michael Schreiber, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}m_{AB}&={\frac {y_{B}-y_{A}}{x_{B}-x_{A}}}={\frac {\sin \theta }{\cos \theta +1}}\\[2pt]m_{BC}&={\frac {y_{C}-y_{B}}{x_{C}-x_{B}}}={\frac {-\sin \theta }{-\cos \theta +1}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee5dc2addbb1431f311cd2c27338a8de3f4c7750)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&m_{AB}\cdot m_{BC}\\[4pt]={}&{\frac {\sin \theta }{\cos \theta +1}}\cdot {\frac {-\sin \theta }{-\cos \theta +1}}\\[4pt]={}&{\frac {-\sin ^{2}\theta }{-\cos ^{2}\theta +1}}\\[4pt]={}&{\frac {-\sin ^{2}\theta }{\sin ^{2}\theta }}\\[4pt]={}&{-1}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/deab92c09e650d952bdc371536a5dade26809ff9)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}0&=(A-B)\cdot (B-C)\\&=(A-B)\cdot (B+A)\\&=|A|^{2}-|B|^{2}.\\[4pt]\therefore \ |A|&=|B|.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d8ebc1b3a63e3b1ddc5ede3bacdd7505cb0c903)