History of chess

This article needs to be updated. (January 2021) |

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1,500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in India; its prehistory is the subject of speculation. From India it spread to Persia, where it was modified in terms of shapes and rules and developed into Shatranj. Following the Arab invasion and conquest of Persia, chess was taken up by the Muslim world and subsequently spread to Europe via Spain (Al Andalus) and Italy (Emirate of Sicily). The game evolved roughly into its current form by about 1500 CE.

"Romantic chess" was the predominant playing style from the late 18th century to the 1880s.[1] Chess games of this period emphasized quick, tactical maneuvers rather than long-term strategic planning.[1] The Romantic era of play was followed by the Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism eras.[1] In the second half of the 19th century, modern chess tournament play began, and the first official World Chess Championship was held in 1886. The 20th century saw great leaps forward in chess theory and the establishment of the World Chess Federation. In 1997, an IBM supercomputer beat Garry Kasparov, the then world chess champion, in the famous Deep Blue versus Garry Kasparov match, ushering the game into an era of computer domination. Since then, computer analysis – which originated in the 1970s with the first programmed chess games on the market – has contributed to much of the development in chess theory and has become an important part of preparation in professional human chess. Later developments in the 21st century made the use of computer analysis far surpassing the ability of any human player accessible to the public. Online chess, which first appeared in the mid-1990s, also became popular in the 21st century.

Origin

Precursors to chess originated in India.[2] There, its early form in the 7th century CE was known as chaturaṅga (Sanskrit: चतुरङ्ग), which translates to "four divisions (of the military)": infantry, cavalry, elephantry, and chariotry. These forms are represented by the pieces that would evolve into the modern pawn, knight, bishop, and rook, respectively.[3]

Chess was introduced to Persia from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of Persian nobility.[4] Around 600 CE in Sassanid Persia, the name for the game became chatrang (Persian: چترنگ), which subsequently evolved to shatranj (Arabic: شطرنج; Persian: شترنج) after the conquest of Persia by the Rashidun Caliphate, due to the lack of native "ch" and "ng" sounds in the Arabic language.[5] The rules were developed further during this time; players started calling "Shāh!" (Persian for "King!") when attacking the opponent's king, and "Shāh Māt!" (Persian for "the king is helpless" – see checkmate) when the king was attacked and could not escape from attack. These exclamations persisted in chess as it traveled to other lands.

The game was taken up by the Muslim world after the early Arab Muslims conquered the Sassanid Empire, with the pieces largely keeping their Persian names. The Moors of North Africa rendered the Persian term "shatranj" as shaṭerej, which gave rise to the Spanish acedrex, axedrez and ajedrez; in Portuguese it became xadrez, and in Greek zatrikion (ζατρίκιον), but in the rest of Europe it was replaced by versions of the Persian shāh ("king"). Thus, the game came to be called lūdus scacc(h)ōrum or scacc(h)ī in Latin, scacchi in Italian, escacs in Catalan, échecs in French (Old French eschecs), schaken in Dutch, Schach in German, szachy in Polish, šahs in Latvian, skak in Danish, sjakk in Norwegian, schack in Swedish, šakki in Finnish, šah in South Slavic languages, sakk in Hungarian and şah in Romanian; there are two theories about why this change happened:

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

- From the exclamation "check" or "checkmate" as it was pronounced in various languages.

- From the first chessmen known of in Western Europe (except Iberia and Greece) being ornamental chess kings brought in as curios by Muslim traders.

The Mongols call the game shatar, and in Ethiopia it is called senterej, both evidently derived from shatranj.

Chess spread directly from the Middle East to Russia, where chess became known as шахматы (shakhmaty, literally "checkmates", a plurale tantum).

The game reached Western Europe and Russia by at least three routes, the earliest being in the 9th century. By the year 1000 it had spread throughout Europe.[7] Introduced into the Iberian Peninsula by the Moors in the 10th century, it was described in a famous 13th-century Spanish manuscript covering shatranj, backgammon and dice named the Libro de los juegos, which is the earliest European treatise on chess as well as being the oldest document on European tables games.

Chess spread throughout the world and many variants of the game soon began taking shape.[8] Buddhist pilgrims, Silk Road traders and others carried it to the Far East where it was transformed and assimilated into a game often played on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares.[9][10] Chaturanga reached Europe through Persia, the Byzantine empire and the expanding Arabian empire.[11] Muslims carried chess to North Africa, Sicily, and Iberia by the 10th century.[12]

The game was developed extensively in Europe. By the late 15th century, it had survived a series of prohibitions and Christian Church sanctions to almost take the shape of the modern game.[13] Modern history saw reliable reference works,[14] competitive chess tournaments,[15] and many new variants. These factors added to the game's popularity,[15] further bolstered by reliable timing mechanisms (first introduced in 1861), effective rules,[15] and charismatic players.[16]

India

The earliest precursor of modern chess is a game called chaturanga, which flourished in India by the 6th century, and is the earliest known game to have two essential features found in all later chess variations—different pieces having different powers (which was not the case with checkers and Go), and victory depending on the fate of one piece, the king of modern chess.[17] A common theory is that India's development of the board, and chess, was likely due to India's mathematical enlightenment involving the creation of the number zero.[5] Other game pieces (speculatively called "chess pieces") uncovered in archaeological findings are considered as coming from other, distantly related board games, which may have had boards of 100 squares or more.[18][non-tertiary source needed]

Chess was designed for an ashtāpada (Sanskrit for "having eight feet", i.e. an 8×8 squared board), which may have been used earlier for a backgammon-type race game (perhaps related to a dice-driven race game still played in south India where the track starts at the middle of a side and spirals into the center).[19] Ashtāpada, the uncheckered 8×8 board served as the main board for playing chaturanga.[20] Other Indian boards included the 10×10 Dasapada and the 9×9 Saturankam.[20] Traditional Indian chessboards often have X markings on some or all of squares a1 a4 a5 a8 d1 d4 d5 d8 e1 e4 e5 e8 h1 h4 h5 h8: these may have been "safe squares" where capturing was not allowed in a dice-driven backgammon-type race game played on the ashtāpada before chess was invented.[21]

The Cox-Forbes theory, proposed in the late 18th century by Hiram Cox, and later developed by Duncan Forbes, asserted that the four-handed game chaturaji was the original form of chaturanga.[22] The theory is no longer considered tenable.[23]

In Sanskrit, the word chaturaṅga literally means "having four limbs (or parts)" and in epic poetry often means "army" (the four parts are elephants, chariots, horsemen, foot soldiers).[4] The name came from a battle formation mentioned in the Indian epic Mahabharata.[21] The game chaturanga was a battle-simulation game[4] which rendered Indian military strategy of the time.[24]

Some people formerly played chess using a die to decide which piece to move. There was an unproven theory that chess started as this dice-chess and that the gambling and dice aspects of the game were removed because of Hindu religious objections.[25]

Scholars in areas to which the game subsequently spread, for example the Arab Abu al-Hasan 'Alī al-Mas'ūdī, detailed the Indian use of chess as a tool for military strategy, mathematics, gambling and even its vague association with astronomy.[26] Mas'ūdī notes that ivory in India was chiefly used for the production of chess and backgammon pieces, and asserts that the game was introduced to Persia from India, along with the book Kelileh va Demneh, during the reign of emperor Nushirwan.[26]

In some variants, a win was by checkmate, or by stalemate, or by "bare king" (taking all of an opponent's pieces except the king).

In some parts of India the pieces in the places of the rook, knight and bishop were renamed by words meaning (in this order) Boat, Horse, and Elephant, or Elephant, Horse, and Camel, but keeping the same moves.[27] In early chess the moves of the pieces were:

| Original name | Modern name | Version | Original move |

|---|---|---|---|

| king | king | all | as now |

| adviser | queen | all | one square diagonally, only |

| elephant | bishop | Persia and west | two squares diagonally (no more or less), but could jump over a piece between |

| an old Indian version | two squares sideways or front-and-back (no more or less), but could jump over a piece between | ||

| southeast and east Asia | one square diagonally, or one square forwards, like four legs and trunk of elephant | ||

| horse | knight | all | as now |

| chariot | rook | all | as now |

| foot-soldier | pawn | all | one square forwards (not two squares from initial position), capturing one square diagonally forward; promoted to queen only |

Two Arab travelers each recorded a severe Indian chess rule against stalemate:[28]

- A stalemated player thereby at once wins.

- A stalemated king can take one of the enemy pieces that would check the king if the king moves.

Iran (Persia)

-

These seven ivory chess pieces are the oldest-known, dating to about 700 CE. The ivory, or the pieces themselves, came from India. [30] They were excavated in 1977 by archaeologist Yuriy Buryakov, at the ancient settlement known as Afrasiab in Samarkand, in Uzbekistan. [31] They are housed today at the Samarkand State Museum. Taken during a loan of the pieces to the Silk Roads Exhibition at the British Museum.]]

-

Persian manuscript from the 14th century describing how an ambassador from India brought chess to the Persian court

-

Shams-i Tabrīzī as portrayed in a 1500 painting in a page of a copy of Rumi's poem dedicated to Shams

-

Chess game between Tha'ālibī and Bākhazarī, 1896 painting by Ludwig Deutsch

-

Iranian courtiers of the Qajar dynasty playing chess in Mazandaran.

The Karnamak-i Ardeshir-i Papakan, a Pahlavi epical treatise about the founder of the Sassanid Persian Empire, mentions the game of chatrang as one of the accomplishments of the legendary hero, Ardashir I, founder of the Empire.[32] The oldest recorded game in chess history is a 10th-century game played between a historian from Baghdad and a pupil.[11][non-tertiary source needed]

A manuscript explaining the rules of the game, called "Matikan-i-chatrang" (the book of chess) in Middle Persian or Pahlavi, still exists.[33] In the 11th-century Shahnameh, Ferdowsi describes a Raja visiting from India who re-enacts the past battles on the chessboard.[26] A translation in English, based on the manuscripts in the British Museum, is given below:[32]

One day an ambassador from the king of Hind arrived at the Persian court of Chosroes, and after an oriental exchange of courtesies, the ambassador produced rich presents from his sovereign and amongst them was an elaborate board with curiously carved pieces of ebony and ivory. He then issued a challenge:

"Oh great king, fetch your wise men and let them solve the mysteries of this game. If they succeed my master the king of Hind will pay tribute as an overlord, but if they fail it will be proof that the Persians are of lower intellect and we shall demand tribute from Iran."

The courtiers were shown the board, and after a day and a night in deep thought one of them, Bozorgmehr, solved the mystery and was richly rewarded by his delighted sovereign.[a]

The Shahnameh goes on to offer an apocryphal account of the origins of the game of chess in the story of Talhand and Gav, two half-brothers who vie for the throne of Hind (India). They meet in battle and Talhand dies on his elephant without a wound. Believing that Gav had killed Talhand, their mother is distraught. Gav tells his mother that Talhand did not die by the hands of him or his men, but she does not understand how this could be. So the sages of the court invent the game of chess, detailing the pieces and how they move, to show the mother of the princes how the battle unfolded and how Talhand died of fatigue when surrounded by his enemies.[34] The poem uses the Persian term "Shāh māt" (check mate) to describe the fate of Talhand.[35]

The philosopher and theologian Al-Ghazali mentions chess in The Alchemy of Happiness (c. 1100). He uses it as a specific example of a habit that may cloud a person's good disposition:[36]

Indeed, a person who has become habituated to gaming with pigeons, playing chess, or gambling, so that it becomes second-nature to him, will give all the comforts of the world and all that he has for those (pursuits) and cannot keep away from them.

The appearance of the chess pieces had altered greatly since the times of chaturanga, with ornate pieces and chess pieces depicting animals giving way to abstract shapes. This is because of a Muslim ban on the game's lifelike pieces, as they were said to have been too like idols.[5] The Islamic sets of later centuries followed a pattern which assigned names and abstract shapes to the chess pieces, as Islam forbids depiction of animals and human beings in art.[37][page needed] These pieces were usually made of simple clay and carved stone.

East Asia

China

As a strategy board game played in China, chess is believed to have been derived from the Indian chaturanga.[38] Chaturanga was transformed into the game xiangqi where the pieces are placed on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares.[39] The object of the Chinese variation is similar to chaturanga, i.e. to render helpless the opponent's king, known as "general" on one side and "governor" on the other.[40] Chinese chess also borrows elements from the game of Go, which was played in China since at least the 6th century BC. Owing to the influence of Go, Chinese chess is played on the intersections of the lines on the board, rather than in the squares. The game of Xiangqi is also unique in that the middle rank represents a river, and is not divided into squares.[41] Chinese chess pieces are usually flat and resemble those used in checkers, with pieces differentiated by writing their names on the flat surface.[39]

An alternative origin theory contends that chess arose from xiangqi or a predecessor thereof, existing in China since the 3rd century BC.[42] David H. Li, a translator of ancient Chinese texts, hypothesizes that general Han Xin drew on the earlier game of Liubo to develop an early form of Chinese chess in the winter of 204–203 BC.[42] The German chess historian Peter Banaschak, however, points out that Li's main hypothesis "is based on virtually nothing." He notes that the "Xuanguai lu", authored by the Tang dynasty minister Niu Sengru (779–847), remains the first real source on the Chinese chess variant xiangqi.[43]

Japan

A prominent variant of chess in East Asia is the game of shogi, transmitted from India to China and Korea before finally reaching Japan.[44] The three distinguishing features of shogi are:

- The captured pieces may be reused by the captor and played as a part of the captor's forces.

- Pawns capture as they move, one square straight ahead.[45]

- The board is 9×9, with a second gold general on the other side of the king.

Drops were not originally part of shogi. In the 13th century, shogi underwent an expansion, creating the game of dai shogi, played on a 15×15 board with many new pieces, including the independently invented rook, bishop and queen of modern Western chess, the drunk elephant that promotes to a second king, and also the even more powerful lion, which among other idiosyncrasies has the power to move or capture twice per turn. Around the 14th or 15th centuries, the popularity of dai shogi then waned in favour of the smaller chu shogi, played on a smaller 12×12 board which removed the weakest pieces from dai shogi, similarly to the development of Courier chess in the West. In the meantime, the original 9×9 shogi, now termed sho shogi, continued to be played, but was regarded as less prestigious than chu shogi and dai shogi. Chu shogi was very popular in Japan, and the rook, bishop, and drunk elephant from it were added to sho shogi, where the first two remain today.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, yet more shogi variants were described, on large boards and with many more pieces. The 1694 book Shōgi Zushiki details tenjiku shogi (16×16), dai dai shogi (17×17), maka dai dai shogi (19×19), and tai shogi (25×25); it also mentions wa shogi (11×11), ko shogi (19×19), and taikyoku shogi (36×36). It is not thought that these games were played very much.

Chu shogi declined in popularity after the addition of drops to sho shogi and the removal of the drunk elephant in the 16th century, becoming moribund around the late 20th century. These changes to sho shogi created what is essentially the modern game of shogi.

Thailand

The Thai variant of chess, makruk is a close living relative to chaturanga, retaining the vizier, non-checkered board, limited promotion, offset kings, and elephant-like bishop move.[46]

Mongolia

Chess is recorded from Mongolian-inhabited areas, where the pieces are now called:

- King: Noyon – Ноён – lord

- Queen: Bers / Nohoi – Бэрс / Нохой – dog (to guard the livestock)

- Bishop: Temē – Тэмээ – camel

- Knight: Morĭ – Морь – horse

- Rook: Tereg – Тэрэг – cart

- Pawn: Hū – Хүү – boy (the piece often showed a puppy)

Names recorded from the 1880s by Russian sources, quoted in Murray,[47][48] among the Soyot people (who at the time spoke the Soyot Turkic language) include: merzé (dog), täbä (camel), ot (horse), ōl (child) and Mongolian names for the other pieces. This game is called shatar; a large 10×10 variant called hiashatar was also played.

The change with the queen is likely due to the Arabic word firzān or Persian word farzīn (= "vizier") being confused with Turkic or Mongolian native words (merzé = "mastiff", bar or bars = "tiger", arslan = "lion").[47][48]

Western chess is now the prevalent form of the game in Mongolia.

East Siberia

Chess was also recorded from the Yakuts, Tunguses, and Yukaghirs; but only as a children's game among the Chukchi. Chessmen have been collected from the Yakutat people in Alaska, having no resemblance to European chessmen, and thus likely part of a chess tradition coming from Siberia.[49]

Arab world

Chess passed from Persia to the Arab world, where its name changed to Arabic shatranj. From there it passed to Western Europe, probably via Spain.

Over the centuries, features of European chess (e.g. the modern moves of queen and bishop, and castling) found their way via trade into Islamic areas. Murray's sources found the old moves of queen and bishop still current in Ethiopia.[50] The game became so popular it was used in writing at that time, played by nobility and regular people. The poet al-Katib once said, "The skilled player places his pieces in such a way as to discover consequences that the ignorant man never sees... thus, he serves the Sultan's interests, by showing how to foresee disaster."[5]

Russia

Chess has 1000 years of history in Russia. Chess was probably brought to Old Russia in the 9th century via the Volga-Caspian trade route. From the 10th century cultural connections with the Byzantine Empire and the Vikings also influenced the history of chess in Russia. The vocabulary in Russian chess has various foreign-language elements and testifies to different influences in the evolution of chess in Russia. Chess is mentioned in folk poems as a popular game and is documented in the Old Russian byliny. Numerous archeological finds of the chess game have already been found in the regions of Old Russia. From 1262 on chess was called in Russia shakhmaty. Various foreign travellers commented that in the 16th century, chess was popular among all classes in Russia. Ivan IV the Terrible, who ruled Russia from 1530 to 1584, is said to have died while playing chess.[51] In 1791 the popular chess book Morals of Chess by Benjamin Franklin was translated into Russian and published in the country. Chess enjoys a very high status in Russia and was gradually introduced as a school subject in all primary schools since 2017.[52][53][54]

Europe

Early history

This paragraph may be confusing or unclear to readers. (May 2013) |

Shatranj made its way via the expanding Islamic Arabian empire to Europe.[11] It also spread to the Byzantine empire, where it was called zatrikion. Chess appeared in Southern Europe during the end of the first millennium, often introduced to new lands by conquering armies, such as the Norman Conquest of England.[13] Previously little known, chess became popular in Northern Europe when figure pieces were introduced.[13]

In the 14th century, Timur played an enlarged variation of the game which is commonly referred to as Tamerlane chess. This complex game involved each pawn having a particular purpose, as well as additional pieces.[55]

The sides are conventionally called White and Black. But, in earlier European chess writings, the sides were often called Red and Black because those were the commonly available colours of ink when handwriting drawing a chess game layout. In such layouts, each piece was represented by its name, often abbreviated (e.g. "ch'r" for French "chevalier" = "knight").

The social value attached to the game – seen as a prestigious pastime associated with nobility and high culture – is clear from the expensive and exquisitely made chessboards of the medieval era.[56] The popularity of chess in the Western courtly society peaked between the 12th and the 15th centuries.[57] The game found mention in the vernacular and Latin language literature throughout Europe, and many works were written on or about chess between the 12th and the 15th centuries.[57] H. J. R. Murray divides the works into three distinct parts: the didactic works e.g. Alexander of Neckham's De scaccis (c. 1180); works of morality like Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium sive super ludo scacchorum (Book of the customs of men and the duties of nobles or the Book of Chess), written by Jacobus de Cessolis; and the works related to various chess problems, written largely after 1205.[57] Chess terms, like check, were used by authors as a metaphor for various situations.[58] Chess was soon incorporated into the knightly style of life in Europe.[59] Peter Alfonsi, in his work Disciplina Clericalis, listed chess among the seven skills that a good knight must acquire.[59] Chess also became a subject of art during this period, with caskets and pendants decorated in various chess forms.[60] Queen Margaret of England had green and red chess sets made of jasper and crystal.[58] Kings Henry I, Henry II and Richard I of England were chess patrons.[18][non-tertiary source needed] King Alfonso X of Castile and Tsar Ivan IV of Russia gained a similar status.[18][non-tertiary source needed]

Saint Peter Damian denounced the bishop of Florence in 1061 for playing chess even when aware of its evil effects on the society.[13] The bishop of Florence defended himself by declaring that chess involved skill and was therefore "unlike other games," and similar arguments followed in the coming centuries.[13] Two incidents in 13th-century London, in which men of Essex resorted to violence resulting in death as an outcome of playing chess, caused further sensation and alarm.[13] The growing popularity of the game – now associated with revelry and violence – alarmed the Church.[13]

The practice of playing chess for money became so widespread during the 13th century that Louis IX of France issued an ordinance against gambling in 1254.[56] This ordinance turned out to be unenforceable and was largely neglected by the common public, and even the courtly society, which continued to enjoy the now-prohibited chess tournaments uninterrupted.[56]

-

Knights Templar playing chess, Libro de los juegos, 1283

-

Otto IV of Brandenburg playing chess with a woman, 1305 to 1340

-

A couple playing chess, ivory mirror case c. 1300

Shapes of pieces

The pieces, which had been nonrepresentational in Islamic countries (see piece values in shatranj), changed shape in Christian cultures. Carved images of men and animals reappeared. The shape of the rook, originally a rectangular block with a V-shaped cut in the top, changed; the two top parts separated by the split tended to get long and hang over, and in some old pictures look like horses' heads. The split top of the piece now called the bishop was interpreted as a bishop's mitre or a fool's cap.

By the mid-12th century, the pieces of the chess set were depicted as kings, queens, bishops, knights and men at arms.[61] Chessmen made of ivory began to appear in North-West Europe, and ornate pieces of traditional knight warriors were used as early as the mid 13th century.[62] The initially nondescript pawn had now found association with the pedes, pedinus, or the footman, which symbolized both infantry and loyal domestic service.[61]

Names of pieces

The following table provides a glimpse of the changes in names and character of chess pieces as they crossed from India through Persia to Europe:[63][64]

| Sanskrit | Bengali | Persian | Arabic | Turkish | Latin | English | Spanish | Portuguese | Italian | French | Catalan | Romanian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raja (King) | Raja (King) | Shah | Malik | Şah | Rex | King | Rey | Rei | Re | Roi | Rei | Rege |

| Mantri (Minister) | Mantri (Minister) | Vazīr (Vizir) | Wazīr/Firz | Vezir | Regina | Queen | Reina/Dama | Rainha/Dama | Regina | Dame | Dama/Reina | Regină |

| Gajah (war elephant) | Hati | Pil | Al-Fīl | Fil | Episcopus/Comes/Calvus | Bishop/Count/Councillor | Alfil/Obispo | Bispo | Alfiere | Fou | Alfil | Nebun |

| Ashva (horse) | Ghora (horse) | Asp | Fars/Hisan | At | Miles/Eques | Knight | Caballo | Cavalo | Cavallo | Cavalier | Cavall | Cal |

| Ratha (chariot) | Nowka | Rokh | Qal`a/Rukhkh | Kale | Rochus/Marchio | Rook/Margrave/Castle | Torre/Roque | Torre | Torre/Rocco | Tour | Torre | Turn/Tură |

| Padati (footman/footsoldier) | Shoinnya | Piadeh | Baidaq/Jondi | Piyon | Pedes/Pedinus | Pawn | Peón | Peão | Pedone/Pedina | Pion | Peó | Pion |

The game, as played during the early Middle Ages, was slow, with many games lasting days.[13] Some variations in rules began to change the shape of the game by the year 1300. A notable, but initially unpopular, change was the ability of the pawn to move two places in the first move instead of one.[65]

In Europe some of the pieces gradually received new names:

- Fers: "queen", because it starts beside the king.

- Aufin: "bishop", because its two points looked like a bishop's mitre. Its Latin name alfinus was reinterpreted many ways.

Early changes to the rules

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

Attempts to make the start of the game run faster to get the opposing pieces in contact sooner included:

- Pawn moving two squares in its first move. This led to the en passant rule: a pawn placed so that it could have captured the enemy pawn if it had moved one square forward was allowed to capture it on the passed square. In Italy, the contrary rule (passar battaglia = "to pass battle") applied: a pawn that moved two squares forward had passed the danger of attack on the intermediate square. It was sometimes not allowed to do this to cover check.[66]

- King jumping once, to make it quicker to put the king safe in a corner. (This eventually led to castling.)

- Queen on its first move moving two squares straight or diagonally to a same-coloured square, with jump. (This rule sometimes also applied to a queen made by promoting a pawn.)

- The short assize. ("assize" = "sitting") Here the pawns started on the third rank; the queens started on d3 and d6 along with the queens' pawns; the players arranged their other pieces as they wished behind their pawns at the start of the game. This idea did not endure.[67]

Other sporadic variations in the rules of chess included:

- Ignoring check from a piece which was covering check, as some said that in theory (in the diagram on the right), Bxe7 would allow Rxc8 in reply.[68]

Introduction of new rules

The queen and bishop remained relatively weak until between 1475 AD and 1500 AD, in Spain (in the Kingdom of Valencia), the queen's and bishop's modern moves started and spread, making chess close to its modern form.[13] The first document showing the Queen (or Dama) moving this way is the allegorical poem Scachs d'amor, written in Catalan in Valencia in 1475.[69][70] This form of chess got such names as "Queen's Chess" or "Mad Queen Chess" (Italian alla rabiosa = "with the madwoman").[71] This led to much more value being attached to the previously minor tactic of pawn promotion.[71] Checkmate became easier and games could now be won in fewer moves.[72][73] These new rules quickly spread in Spain and throughout the rest of Western Europe,[74][75] with the exception of the rules about stalemate, which were finalized in the early 19th century.[76] The modern move of the queen may have started as an extension of its older ability to once move two squares with jump, diagonally or straight. Marilyn Yalom says that the new move of the queen started in Spain: see history of the queen.

In some areas (e.g. Russia), the queen could also move like a knight.

A poem Caïssa published in 1527 led to the chess rook being often renamed as "castle", and the modern shape of the rook chess piece; see Vida's poem for more information.

An Italian player, Gioacchino Greco, regarded as one of the first true professionals of the game, authored an analysis of a number of composed games that illustrated two differing approaches to chess.[14][non-tertiary source needed] His work was influential in popularizing chess, and demonstrated many theories regarding game play and tactics.[14][non-tertiary source needed]

The first full work dealing with the various winning combinations was written by François-André Danican Philidor of France, regarded as the best chess player in the world for nearly 50 years, and published in the 18th century.[14][non-tertiary source needed] He wrote and published L'Analyse des échecs (The Analysis of Chess), an influential work which appeared in more than 100 editions.[14][non-tertiary source needed]

-

A tactical puzzle from Lucena's 1497 book

-

A gaming table with chessboard (Germany, 1735).

-

A Russian set made of walrus ivory, 1750s

-

Portrait of François-André Danican Philidor from L'analyse des échecs. London, second edition, 1777

-

Original Staunton chess pieces by Nathaniel Cooke from 1849

Writings on the theory of how to play chess began to appear in the 15th century. The oldest surviving printed chess book, Repetición de Amores y Arte de Ajedrez (Repetition of Love and the Art of Playing Chess) by Spanish churchman Luis Ramirez de Lucena was published in Salamanca in 1497.[74] Lucena and later masters like Portuguese Pedro Damiano, Italians Giovanni Leonardo Di Bona, Giulio Cesare Polerio and Gioachino Greco or Spanish bishop Ruy López de Segura developed elements of openings and started to analyze simple endgames. In the 18th century the center of European chess life moved from the Southern European countries to France. The two most important French masters were François-André Danican Philidor, a musician by profession, who discovered the importance of pawns for chess strategy, and later Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais who won a famous series of matches with the Irish master Alexander McDonnell in 1834.[77] Centers of chess life in this period were coffee houses in big European cities like Café de la Régence in Paris[78] and Simpson's Divan in London.[79]

As the 19th century progressed, chess organization developed quickly. Many chess clubs, chess books and chess journals appeared. There were correspondence matches between cities; for example the London Chess Club played against the Edinburgh Chess Club in 1824.[80] Chess problems became a regular part of 19th-century newspapers; Bernhard Horwitz, Josef Kling and Samuel Loyd composed some of the most influential problems. In 1843, von der Lasa published his and Bilguer's Handbuch des Schachspiels (Handbook of Chess), the first comprehensive manual of chess theory.

Modern competitive chess

The first recorded chess tournament took place in 1575 in El Escorial, Spain. It was won by the Calabrese Leonardo di Bona.[81]

Competitive chess became visible in 1834 with the La Bourdonnais-McDonnell matches, and the 1851 London Chess tournament raised concerns about the time taken by the players to deliberate their moves. On recording time it was found that players often took hours to analyze moves, and one player took as much as two hours and 20 minutes to think over a single move at the London tournament. The following years saw the development of speed chess, five-minute chess and the most popular variant, a version allowing a bank of time to each player in which to play a previously agreed number of moves, e.g. two hours for 30 moves. In the final variant, the player who made the predetermined number of moves in the agreed time received additional time budget for his next moves. Penalties for exceeding a time limit came in form of fines and forfeiture. Since fines were easy to bear for professional players, forfeiture became the only effective penalty; this added "lost on time" to the traditional means of losing such as checkmate and resigning.[15][non-tertiary source needed]

In 1861 the first time limits, using sandglasses, were employed in a tournament match at Bristol, England. The sandglasses were later replaced by pendulums. Modern clocks, consisting of two parallel timers with a small button for a player to press after completing a move, were later employed to aid the players. A tiny latch called a flag further helped settle arguments over players exceeding time limit at the turn of the 19th century.[15][non-tertiary source needed]

A Russian composer, Vladimir Korolkov, authored a work entitled "Excelsior" in 1958 in which the White side wins only by making six consecutive captures by a pawn.[82][non-tertiary source needed] Position analysis became particularly popular in the 19th century.[82][non-tertiary source needed] Many leading players were also accomplished analysts, including Max Euwe, Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasily Smyslov and Jan Timman.[82][non-tertiary source needed] Digital clocks appeared in the 1980s.[15][non-tertiary source needed]

Another problem that arose in competitive chess was when adjourning a game for a meal break or overnight. The player who moved last before adjournment would be at a disadvantage, as the other player would have a long period to analyze before having to make a reply when the game was resumed. Preventing access to a chess set to work out moves during the adjournment would not stop him from analyzing the position in his head. Various strange ideas were attempted, but the eventual solution was the "sealed move". The final move before adjournment is not made on the board but instead is written on a piece of paper which the referee seals in an envelope and keeps safe. When the game is continued after adjournment, the referee makes the sealed move and the players resume.

Birth of a sport (1850–1945)

The first modern chess tournament was held in London in 1851 and won, surprisingly, by German Adolf Anderssen, who was relatively unknown at the time. Anderssen was hailed as the leading chess master, and his brilliant, energetic attacking style became typical for the time, although it was retrospectively regarded as strategically shallow.[83][84] Sparkling games like Anderssen's Immortal game and Evergreen Game or Morphy's Opera game were regarded as the highest possible summit of the chess art.[85]

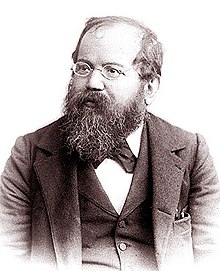

Deeper insight into the nature of chess came with two younger players. American Paul Morphy, an extraordinary chess prodigy, won against all important competitors, including Anderssen, during his short chess career between 1857 and 1863. Morphy's success stemmed from a combination of brilliant attacks and sound strategy; he intuitively knew how to prepare attacks.[86] Prague-born Wilhelm Steinitz later described how to avoid weaknesses in one's own position and how to create and exploit such weaknesses in the opponent's position.[87] In addition to his theoretical achievements, Steinitz founded an important tradition: his triumph over the leading Polish-German master Johannes Zukertort in 1886 is regarded as the first official World Chess Championship. Steinitz lost his crown in 1894 to a much younger German mathematician Emanuel Lasker, who maintained this title for 27 years, the longest tenure of all World Champions.[88]

It took a prodigy from Cuba, José Raúl Capablanca (World champion 1921–27), who loved simple positions and endgames, to end the German-speaking dominance in chess; he was undefeated in tournament play for eight years until 1924. His successor was Russian-French Alexander Alekhine, a strong attacking player, who died as the World champion in 1946, having briefly lost the title to Dutch player Max Euwe in 1935, regaining it two years later.[89]

Between the world wars, chess was revolutionized by the new theoretical school of so-called hypermodernists like Aron Nimzowitsch and Richard Réti. They advocated controlling the center of the board with distant pieces rather than with pawns, inviting opponents to occupy the center with pawns which become objects of attack.[90]

Since the end of 19th century, the number of annually held master tournaments and matches quickly grew. Some sources state that in 1914 the title of chess grandmaster was first formally conferred by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia to Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall, but this is a disputed claim.[91] The tradition of awarding such titles was continued by the World Chess Federation (FIDE), founded in 1924 in Paris. In 1927, Women's World Chess Championship was established; the first to hold it was Czech-English master Vera Menchik.[92]

During World War II, many prominent chess players died or were killed, including: Isaak Appel, Zoltan Balla, Sergey Belavenets, Henryk Friedman, Achilles Frydman, Eduard Gerstenfeld, Alexander Ilyin-Genevsky, Mikhail Kogan, Jakub Kolski, Leon Kremer, Arvid Kubbel, Leonid Kubbel, Salo Landau, Moishe Lowtzky, Vera Menchik, Vladimir Petrov, David Przepiorka, Ilya Rabinovich, Vsevolod Rauzer, Nikolai Riumin, Endre Steiner, Mark Stolberg, Abram Szpiro, Karel Treybal, Alexey Troitzky, Samuil Vainshtein, Heinrich Wolf, and Lazar Zalkind.[93]

Post-war era (1945 and later)

After the death of Alekhine, a new World Champion was sought in a tournament of elite players ruled by FIDE, who have controlled the title since then, with a sole interruption. The winner of the 1948 tournament, Russian Mikhail Botvinnik, ushered in an era of Soviet dominance in the chess world. Until the end of the Soviet Union, there was only one non-Soviet champion, American Bobby Fischer (champion 1972–75).[94]

In the previous informal system, the World Champion decided which challenger he would play for the title and the challenger was forced to seek sponsors for the match.[95] FIDE set up a new system of qualifying tournaments and matches. The world's strongest players were seeded into "Interzonal tournaments", where they were joined by players who had qualified from "Zonal tournaments". The leading finishers in these Interzonals would go on the "Candidates" stage, which was initially a tournament, later a series of knock-out matches. The winner of the Candidates would then play the reigning champion for the title. A champion defeated in a match had a right to play a rematch a year later. This system worked on a three-year cycle.[95]

Botvinnik participated in championship matches over a period of fifteen years. He won the world championship tournament in 1948 and retained the title in tied matches in 1951 and 1954. In 1957, he lost to Vasily Smyslov, but regained the title in a rematch in 1958. In 1960, he lost the title to the Latvian prodigy Mikhail Tal, an accomplished tactician and attacking player. Botvinnik again regained the title in a rematch in 1961.

Following the 1961 event, FIDE abolished the automatic right of a deposed champion to a rematch, and the next champion, Armenian Tigran Petrosian, a genius of defense and strong positional player, was able to hold the title for two cycles, 1963–69. His successor, Boris Spassky from Russia (1969–72), was a player able to win in both positional and sharp tactical style.[96]

The next championship saw the first non-Soviet challenger since World War II, Bobby Fischer, who defeated his Candidates opponents by unheard-of margins and won the world championship match.

Kasparov-Karpov rivalry and chess computers (1975-2013)

In 1975, Fischer refused to defend his title against Soviet Anatoly Karpov when FIDE refused to meet his demands, and Karpov obtained the title by default. Karpov defended his title twice against Viktor Korchnoi and dominated the 1970s and early 1980s with a string of tournament successes.[97]

Karpov's reign finally ended in 1985 at the hands of another Russian player, Garry Kasparov. Kasparov and Karpov contested five world title matches between 1984 and 1990; Karpov never won his title back.[98]

In 1987, the computer database program ChessBase was launched with the support of Garry Kasparov.[99] Kasparov was an early adopter of computer chess databases, and soon computers played an integral role in the training and preparation of the world's top players.

In 1993, Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short cut ties with FIDE to organize their own match for the title and formed a competing Professional Chess Association (PCA). From then until 2006, there were two simultaneous World Champions and World Championships: the PCA or Classical champion extending the Steinitzian tradition in which the current champion plays a challenger in a series of many games; the other following FIDE's new format of many players competing in a tournament to determine the champion. Kasparov lost his Classical title in 2000 to Vladimir Kramnik of Russia.

Earlier, in 1996, Kasparov played a pair of six-game exhibition matches against IBM supercomputer Deep Blue. He won the first match 4-2 but lost the rematch 3½-2½.[100] This defeat symbolically heralded the arrival of chess engines playing at grandmaster strength. In 1999, Kasparov as the reigning world champion played a game online against the world team composed of more than 50,000 participants from more than 75 countries. The moves of the world team were decided by plurality vote, and after 62 moves played over four months Kasparov won the game.[101] In 2006, Kramnik lost a match against Deep Fritz, effectively ending the era of human-computer chess competition.

The FIDE World Chess Championship 2006 reunified the titles, when Kramnik beat the FIDE World Champion Veselin Topalov and became the undisputed World Chess Champion.[102] In September 2007, Viswanathan Anand from India became the next champion by winning a championship tournament.[103] In October 2008, Anand retained his title, decisively winning the rematch against Kramnik.[104]

Carlsen and the online chess boom (2013-Present)

Anand retained his title until 2013, when he lost it to Magnus Carlsen from Norway. Carlsen defended his title four times, reaching an all-time record FIDE rating of 2882 in May of 2014. Carlsen was the first player to hold the World Classical, Rapid, and Blitz chess championship titles simultaneously. However, he declined to defend his title in 2023, and thus relinquished it to 2022 Candidates Tournament runner-up Ding Liren, who won the title in a match against Candidates winner Ian Nepomniachtchi.[105][106] Nevertheless, Carlsen remains a dominant player, retaining the world's highest rating and winning the FIDE World Cup in 2023.

In recent years, online chess through the use of internet chess servers have exploded in popularity. Internet chess servers have existed since 1992 with the creation of the subscription service Internet Chess Club,[107] but today the majority of top-level players have moved to freemium websites like Chess.com (founded in 2007) and, to a lesser extent, free website Lichess (launched in 2010). These websites feature quick pairing systems and site-specific ratings for bullet, blitz, rapid, and/or classical time controls. They also include additional features such as puzzles, engine analysis, databases, user-created libraries, community blogs and forums, news and articles, video lessons, and more. They also host tournaments where top grandmasters compete for prizes, creating an around-the-clock chess media ecosystem.

In 2020, online chess experienced a spike in popularity due to interest in the Netflix miniseries The Queen's Gambit released amidst the 2020 Covid Pandemic. In 2023, an even larger spike occurred, driven in large part by viral chess engine Mittens, a playable bot on chess.com.[108] Chess has become an esport, with many top players such as Magnus Carlsen and American Grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura streaming their games live.[109][110] Other popular chess content creators include International Master Levy Rozman (Gothamchess) and Antonio Radić (Agadmator).[111]

Chess engines have also radically transformed, incorporating new technologies into their move search and evaluation functions. Previously, dominant computers such as Rybka (released in 2005), Stockfish (2008), Houdini (2010), and Komodo (2010) used a hand-crafted evaluation using variables such as space and piece mobility. In 2017, chess engine AlphaZero won a controversial match[112] against Stockfish using a relatively novel neural network system. Since then, all of the top engines, including Stockfish, Komodo Dragon, Leela Chess Zero (2018), and Torch (2023), have incorporated efficiently updatable neural networks (NNUEs) into their evaluation functions.

Rule changes

Stalemate was originally considered an inferior form of victory; at various times it has been considered a win, a draw, or even a loss for the player delivering it. Since the 18th century, it has been considered a draw.

The convention that White moves first was established in the 19th century; previously either White or Black could move first.

Castling rules have varied, variations persisting in Italy until the late 19th century.

Rules concerning draws by repetition and the fifty-move rule have been refined and now require a formal claim. Perpetual check is no longer included in the rules of chess.

There have been no recent changes to the moves of the pieces, but the wording of some rules has been changed for the purposes of clarity.

The London 1883 chess tournament introduced chess clocks, creating a new rule for loss on time.

In line with the rule against receiving outside assistance, if a player's mobile phone or other electronic device generates sound, the player is immediately forfeited.[113] In amateur tournaments players are asked to hand their phones to the tournament director; in professional tournaments they may be required to go through a metal detector.

See also

- Outline of chess § History of chess

- Chess in the arts

- Computer chess

- History of chess engines

- List of chess historians

- List of chess variants

- List of games that Buddha would not play

- School of chess

- Timeline of chess

- Wheat and chessboard problem

Notes

- ^ R. C. Bell, commenting on the objective impossibility of divining the rules of the game by scrutinizing the equipment, suggested in Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations (Vol. I p. 57) that Bozorgmehr likely found the rules by bribing the Indian ambassador.

References

- ^ a b c David Shenk (2007). The Immortal Game: A History of Chess. Knopf Doubleday. p. 99. ISBN 9780385510103.

- ^ (Murray 1913, pp. 26-27)(Murray 1913, pp. 51-52)

- ^ Murray, Davidson, Hooper & Whyld, and Golombek all give this correspondence, with the bishop corresponding to the elephant and the rook corresponding to a chariot. Bird (pp 4, 46) exchanges the bishop and rook.

- ^ a b c Meri 2005: 148

- ^ a b c d Shenk, David. "The Immortal Game." Doubleday, 2006.

- ^ "The History Of Chess". ChessZone. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Hooper and Whyld, 144-45 (first edition)

- ^ Gollon, John. Chess Variations, Ancient, Regional, and Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Publishers, Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan, 1968. Sec. One, Sec. Two

- ^ (Murray 1913, pp. 119ff)

- ^ Remus, Horst, "The Origin of Chess and the Silk Road" Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, The Silk Road journal, The Silkroad Foundation, v.1(1), January 15, 2003.

- ^ a b c Chess: Introduction to Europe (Encyclopædia Britannica 2007)

- ^ (Murray 1913, p. 402)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Riddler 1998

- ^ a b c d e Chess: Development of Theory (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ a b c d e f Chess: The time element and competition (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ Lasker, Edward. The Adventure of Chess. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York, 1949, 1950, 1959. pp. 87–117

- ^ Lasker, Edward. The Adventure of Chess. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York, 1949, 1950, 1959. pp. 3–4

- ^ a b c Chess: Ancient precursors and related games (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ (Murray 1913, p. 40)

- ^ a b Wilkins 2002: 46

- ^ a b (Murray 1913, p. 42)

- ^ Bell (1979) Vol. I, pp.52-57

- ^ Hooper 1992: 74

- ^ Kulke 2004: 9

- ^ Wilkins 2002: 48

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 1943

- ^ (Murray 1913, p. 27)

- ^ A History of Chess

- ^ See the chess set's page Archived 2021-03-01 at the Wayback Machine on the museum's website.

- ^ Silk Roads (2024), pp. 151–52

- ^ Die Schachfiguren aus Afrasiab: Fragen an die Wissenschaft zur Deutung, Zeitstellung und Ikonographie by Manfred Eder, Antike Welt Vol. 25, No. 1 (1994)

- ^ a b Bell 1979: 57

- ^ Peshotan Behramjee Sanjana, "Ganjeshāyagān, Andarze ātrepāt mārāspandān, Mādigāne chatrang, and Andarze khusroe kavātān : the original Pehlvi text, the same translated into the Gujarati and English languages, a commentary and a glossary of select words" Archived 2018-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Warner & Warner 2008, p. 394-402.

- ^ Yalom 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Al-Ghazali, The Alchemy of Happiness, Mohammad Nur Abdus Salam, p. 27-28

- ^ Eales 1985.

- ^ Gollon, John. Chess Variations, Ancient, Regional, and Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Publishers, Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan, 1968. p.139

- ^ a b Bell 1979, V.I p.66

- ^ (Murray 1913, p.126)

- ^ "The History Of Chess". ChessZone. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ a b Li 1998

- ^ "Banaschak: A story well told is not necessarily true – being a critical assessment of David H. Li's "The Genealogy of Chess"". Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ (Murray 1913, p.138)

- ^ Gollon, John. Chess Variations, Ancient, Regional, and Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Publishers, Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan, 1968. p.167

- ^ Gollon, John. Chess Variations, Ancient, Regional, and Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Co.: Publishers, Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan, 1968. pp.197–198

- ^ a b (Murray 1913, p. 367)

- ^ a b (Murray 1913, p. 372)

- ^ (Murray 1913, pp. 373-374)

- ^ (Murray 1913, p. 364)

- ^ Waliszewski, Kazimierz; Mary Loyd (1904). Ivan the Terrible. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. pp. 377–78.

- ^ Richards. "The Vocabulary of the Russian Chessboard". New Zealand Slavonic Journal. 2: 63–72 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "First Russian chessmen". history.chess.free.fr. Archived from the original on 2019-10-25. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ^ правды», Никита КЛЮЧЕНКОВ | Сайт «Комсомольской (2019-08-05). "Шахматы стали обязательным школьным предметом". KP.RU - сайт «Комсомольской правды» (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ^ Rudolph, Jess. "The History and Variants in West Asia." Case Western Reserve University.

- ^ a b c Vale 2001: 172

- ^ a b c Gamer 1954

- ^ a b Vale 2001: 177

- ^ a b Vale 2001: 171

- ^ Vale 2001: 152

- ^ a b Vale 2001: 173

- ^ Vale 2001: 151

- ^ Vale 2001: 174

- ^ Murray, H. J. R.: 1913

- ^ Bell (1979), pp. 62–64

- ^ Murray, H. J. R. (1952). "6: Race-Games". A History of Board-Games Other than Chess. Hacker Art Books. ISBN 0-87817-211-4.

- ^ (Murray 1913, pp. 476-478)

- ^ (Murray 1913, p. 509)

- ^ "Francesco di Castellvi vs Narciso Vinyoles (1475) "Old in Chess"". www.chessgames.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-28. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Valencia and the origin of modern chess". Chess Vibes. 2009-09-13. Archived from the original on 2009-09-26. Retrieved 2021-10-31.

- ^ a b (Murray 1913, p.777)

- ^ Lasker, Edward. The Adventure of Chess. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York, 1949, 1950, 1959. p. 37

- ^ Davidson (1981), p. 13–17

- ^ a b Calvo, Ricardo. Valencia Spain: The Cradle of European Chess Archived 2009-01-08 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 December 2006

- ^ An analysis from the feminist perspective: Weissberger, Barbara F. (2004). Isabel Rules: constructing queenship, wielding power. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4164-1. OCLC 217447754. P. 152ff

- ^ See History of the stalemate rule.

- ^ "Louis Charles Mahe De La Bourdonnai". Chessgames.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ Metzner, Paul (1998). Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20684-3. OCLC 185289629. Online version Archived 2008-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bird, Henry Edward. Chess History and Reminiscences Archived 2020-11-09 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 December 2006

- ^ "London Chess Club". Chessgames.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ Soltis, Andrew (2020). The Art of the Game of Chess. CUA Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780813232812.

- ^ a b c Chess: Chess composition (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^ World Title Matches and Tournaments - Chess history. worldchessnetwork.com

- ^ Hartston, W. (1985). The Kings of Chess. Pavilion Books Limited. p. 36. ISBN 0-06-015358-X.

- ^ Burgess, Graham, Nunn, John and Emms, John (1998). The Mammoth Book of the World's Greatest Chess Games. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0587-6. OCLC 40209258.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), p. 14. - ^ Shibut, Macon (2004). Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43574-1. OCLC 55639730.

- ^ Steinitz, William; Landsberger, Kurt (2002). The Steinitz Papers: Letters and Documents of the First World Chess Champion. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1193-7. OCLC 48550929.

- ^ Kasparov (1983a)

- ^ Kasparov 1983b

- ^ Fine (1952)

- ^ This is stated for example in The Encyclopaedia of Chess (1970, p.223) by Anne Sunnucks, but this is also disputed by Edward Winter (chess historian) in his Chess Notes 5144 and 5152 Archived 2016-06-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Menchik at ChessGames.com Archived 2019-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 December 2006

- ^ "World War II and Chess". chess.com. 2015-01-10. Archived from the original on 2021-02-04. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ^ Kasparov 2003b, 2004a, 2004b, 2006

- ^ a b "Chess History". Archived from the original on 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Kasparov 2003b, 2004a

- ^ Kasparov 2003a, 2006

- ^ Keene, Raymond (1993). Gary Kasparov's Best Games. B. T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-7296-0. OCLC 29386838., p. 16.

- ^ "Kasparov and the start of ChessBase". Chess News. 2020-11-23. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ "CHESSGAMES.COM * Chess game search engine". www.chessgames.com. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Harding, T. (2002). 64 Great Chess Games, Dublin: Chess Mail. ISBN 0-9538536-4-0.

- ^ Kramnik at ChessGames.com Archived 2020-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 December 2006

- ^ "Viswanathan Anand regains world chess title". Reuters. 2007-09-30. Archived from the original on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ^ "Anand draws 11th game, wins world chess title". IBN Live. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Mather, Victor (2022-07-20). "Lacking Motivation, Magnus Carlsen Will Give Up World Chess Title". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-07-21. Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ Graham, Bryan Armen (2023-04-30). "Ding Liren succeeds Carlsen as world chess champion with gutsy playoff win". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2023-05-10. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ "FICS - Free Internet Chess Server - Internet Chess Anniversary". www.freechess.org. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Team (CHESScom), Chess com (2023-01-23). "Chess Is Booming! And Our Servers Are Struggling". Chess.com. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Pappalardo, Charlie (2023-04-05). "Streaming, strategy and the sudden resurgence of chess". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on 2023-07-19. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ Browning, Kellen (2020-09-07). "Chess (Yes, Chess) Is Now a Streaming Obsession". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-09-20. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ Copeland (SamCopeland), Sam (2021-09-18). "The Top YouTube Chess Channels | Congrats To GothamChess On #1!!!". Chess.com. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Doggers (PeterDoggers), Peter (2017-12-08). "AlphaZero Chess: Reactions From Top GMs, Stockfish Author". Chess.com. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ "FIDE LAWS of CHESS - Article 12: The conduct of the players" (PDF). www.fide.com/. World Chess Federation. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Chess: Ancient precursors and related games.". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "Chess: Development of Theory". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "Chess: The time element and competition". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "Chess: Chess composition". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "Chess (History): Standardization of rules". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- "Chess: Set design.". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- "Chess: Introduction to Europe". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- "Chinese chess". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- "Shogi". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

WWW

- Banaschak, Peter. "A story well told is not necessarily true : a critical assessment of David H. Li's The Genealogy of Chess". Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

Books

- Bell, Robert Charles (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- Bird, Henry Edward (1893). Chess History and Reminiscences. London. (Republished version by Forgotten Books). ISBN 1-60620-897-7.

- Cazaux, Jean-Louis; Knowlton, Rick (2017). A World of Chess. Its Development and Variations through Centuries and Civilizations. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9427-9.

- Davidson, Henry A. (1981) [1949]. A Short History of Chess. McKay. ISBN 0-679-14550-8. OCLC 17340178.

- Eales, Richard (1985). Chess, The History of a Game. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816011957.

- Forbes, Duncan (1860). The History of Chess: From the Time of the Early Invention of the Game in India Till the Period of Its Establishment in Western and Central Europe. London: W. H. Allen & Co.

- Golombek, Harry (1977). Golombek's Encyclopedia of Chess. Crown Publishing. ISBN 0-517-53146-1.

- Golombek, Harry (1976). A History of Chess. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-8266-5.

- Harding, Tim (2003). Better Chess for Average Players. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29029-8. OCLC 33166445.

- Hooper, David Vincent; Whyld, Kenneth (1992). The Oxford Companion to Chess. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- Hooper, David and Whyld, Kenneth (1992). The Oxford Companion to Chess, Second edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9. OCLC 25508610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Reprint: (1996) ISBN 0-19-280049-3 - Kasparov, Garry (2003a). My Great Predecessors, part I. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-330-6. OCLC 223602528.

- Kasparov, Garry (2003b). My Great Predecessors, part II. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-342-X. OCLC 223906486.

- Kasparov, Garry (2004a). My Great Predecessors, part III. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-371-3. OCLC 52949851.

- Kasparov, Garry (2004b). My Great Predecessors, part IV. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-395-0. OCLC 52949851.

- Kasparov, Garry (2006). My Great Predecessors, part V. Everyman Chess. ISBN 1-85744-404-3. OCLC 52949851.

- Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32920-5.

- Leibs, Andrew (2004). Sports and Games of the Renaissance. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32772-6

- Li, David H. (1998). The Genealogy of Chess. Premier Pub. Co. ISBN 0-9637852-2-2.

- Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96690-6.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-936317-01-4.

- Musser Golladay, Sonja, "Los Libros de acedrex dados e tablas: Historical, Artistic and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X's Book of Games" (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007)

- Needham, Joseph (1962). "Thoughts on The Origin of Chess". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- Needham, Joseph; Ronan, Colin A. (June 1985). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31536-4.

- Needham, Joseph; Ronan, Colin A. (July 1986). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31560-3.

- Saidy, Anthony. The battle of chess ideas (Batsford, 1972); scholarly history; The March of Chess Ideas: How the Century's Greatest Players Have Waged the War Over Chess Strategy (1994)

- Shenk, David (2007). The Immortal Game: A History of Chess. Knopf Doubleday. p. 99. ISBN 9780385510103.

- Vale, M. G. A. (2001). The Princely Court: Medieval Courts and Culture in North-West Europe, 1270-1380. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926993-9.

- Wilkins, Sally (2002). Sports and Games of Medieval Cultures. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31711-9.

- Yalom, Marilyn (2004). Birth of the Chess Queen: a History (Illustrated ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-009064-2.

- Firdausí (1915). The Sháhnámá of Firdausí. Vol. VII. Trans. Warner, Arthur George & Warner, Edmond. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. ISBN 0-415-24545-1.

Journals

- Anand, Viswanathan, "The Indian Defense", TIME, Thursday, Jun. 19, 2008. An article on the history of chess by the 2007-10 chess world champion.

- Gamer, Helena M. (October 1954). "The Earliest Evidence of Chess in Western Literature: The Einsiedeln Verses". Speculum. 29 (4). Medieval Academy of America: 734–750. doi:10.2307/2847098. JSTOR 2847098. S2CID 162079385.

- Gordon, Stewart (July–August 2009). "The Game of Kings". Saudi Aramco World. 60 (4). Houston: Aramco Services Company: 18–23. Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. (PDF version)

- Riddler, Ian; Denison, Simon (February 1998). "When there is no end to a good game". British Archaeology (31). United Kingdom: Council for British Archaeology. ISSN 1357-4442. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016.

- Wilkinson, Charles K (May 1943). "Chessmen and Chess". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series 1 (9). The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 271–279. doi:10.2307/3257111. JSTOR 3257111. Archived from the original on 2010-09-24. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

![Iranian shatranj set, glazed fritware, 12th century, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e6/Chess_Set_MET_DP170393.jpg/213px-Chess_Set_MET_DP170393.jpg)

![These seven ivory chess pieces are the oldest-known, dating to about 700 CE. The ivory, or the pieces themselves, came from India. [30] They were excavated in 1977 by archaeologist Yuriy Buryakov, at the ancient settlement known as Afrasiab in Samarkand, in Uzbekistan. [31] They are housed today at the Samarkand State Museum. Taken during a loan of the pieces to the Silk Roads Exhibition at the British Museum.]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/Chessmen_from_Samarkhand.jpg/121px-Chessmen_from_Samarkhand.jpg)