Ordnungspolizei

| Order Police Ordnungspolizei | |

|---|---|

Orpo flag | |

| |

| Common name | Grüne Polizei |

| Abbreviation | Orpo |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 26 June 1936 |

| Dissolved | 1945 |

| Employees | 401,300 (1944 est.)[1] |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Legal jurisdiction | |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Berlin NW 7, Unter den Linden 72/74 52°30′26″N 13°22′57″E / 52.50722°N 13.38250°E |

| Elected officers responsible |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Interior Ministry |

The Ordnungspolizei (Orpo, German: [ˈɔʁdnʊŋspoliˌtsaɪ], meaning "Order Police") were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945.[2] The Orpo was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction was removed in favour of the central Nazi government ("Reich-ification", Verreichlichung, of the police). The Orpo was controlled nominally by the Interior Ministry, but its executive functions rested with the leadership of the Schutzstaffel (SS) until the end of World War II,[2] The top "leaders" were almost all SS members. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was appointed Chief of the German Police in the Reich Ministry of the Interior. Owing to their green uniforms, Orpo members were also referred to as Grüne Polizei (green police). The force was first established as a centralised organisation uniting the municipal, city, and rural uniformed police that had been organised on a state-by-state basis.[2]

The Ordnungspolizei encompassed virtually all of Nazi Germany's law-enforcement and emergency response organisations, including fire brigades, coast guard, and civil defence. Himmler and Kurt Daluege, chief of the Orpo, worked to transform the police force into militarised formations ready to serve the regime's aims of conquest and racial annihilation. Police troops were first formed into battalion-sized formations for the invasion of Poland, where they were deployed for security and policing purposes, also taking part in executions and mass deportations.[3] During World War II, the force was tasked with policing the civilian population of the occupied and colonised countries.[4] In 1941, the Orpo's activities escalated to genocide with the Order Police battalions, formed into independent regiments or attached to Wehrmacht security divisions and Einsatzgruppen, perpetrated mass-murder in the Holocaust and were responsible for crimes against humanity and genocide.

History

[edit]Almost immediately after the Nazis seized power, they instituted measures to gain political control of German police and to use them against their perceived enemies.[5] Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had already been deputy chief of the Prussian secret police, when by decree of June 17, 1936, he was appointed Chief of the Police force; he performed both functions in parallel and was officially (and publicly) referred to as "Reichsführer-SS and Chief of the German Police in the Reich Ministry of the Interior".[6] Although nominally subordinate to Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick, Himmler could participate in meetings of the Reich Cabinet—when and if police agendas were discussed.[7]

Traditionally, law enforcement in Germany had been a state and local matter. When Himmler was given the lead over all of Germany's uniformed law enforcement agencies in 1936 he divided the police into two main areas: the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo or Order Police) under the command of Kurt Daluege and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo or security police) under Reinhard Heydrich.[8] The Orpo assumed duties of regular uniformed law enforcement while the SiPo was made up by the combined forces of the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo; secret state police) and the Kriminalpolizei (Kripo; criminal investigation police). The Gestapo were a political police agency with additional legally guaranteed powers of arrest. On 27 September 1939, shortly after the start of World War II, the SiPo and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; SS security service) were folded into the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA).[9] The RSHA symbolised the close connection between the SS (a party organisation) and the police (a state organisation).[10][11] The Order Police (uniformed police, enforcement police) remained in the Ministry of the Interior. Himmler's multiple attempts to increase the proportion of SS members in the Orpo failed.[12]

Himmler pursued the amalgamation of SS and police into a form of "State Protection Corps" (Staatsschutzkorps), and used the expanded reach the police powers gave him to persecute ideological opponents and "undesirables" of the Nazi regime such as Jews, freemasons, churches, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and other groups defined as "asocial".[13] The Nazi conception of criminality was racial and biological, holding that criminal traits were hereditary, and had to be exterminated to purify German blood. As a result, even ordinary criminals were consigned to concentration camps to remove them from the German racial community (Volksgemeinschaft) and ultimately exterminate them.[14]

The Order Police was the executing force of the inhumane goals pursued by Himmler and the RSHA. Instructions for the Orpo came through the regional political administrative authorities and/or the Higher SS and Police Leaders (HSSPF)—the latter had authority to command both police branches and the SS-forces, since Himmler intended all along for harmony between both the police and the SS.[15][a] Most of the battalions of the Order Police troops in the east were deployed for the expulsion and extermination of the Jewish population, since parts were assigned to the SS Einsatzgruppen.[16] Their personnel were used to guard ghettos or to carry out mass shootings. Order police played an executive role in the Holocaust, by "both career professionals and reservists, in both battalion formations and precinct service" (Einzeldienst) by providing men for the tasks involved.[17]

Organization

[edit]The German Order Police had grown to 244,500 men by mid-1940.[18] In preparation for the war of aggression and conquest, a replacement police force was set up as early as 1937 to take over patrol and guard duties. This auxiliary police could be activated by decree for service in their home districts and had grown to over 90,000 by the beginning of the war. These older men were drafted and conscripted into the reserve police, and in the course of the war, veterans were also called up. The majority of them served in their home environment, some were deployed in police reserve battalions.[19]

In 1936, Himmler divided the Nazi police into two branches, each in Berlin.[20] The central command office known as the Ordnungspolizei Hauptamt was housed in the old office building of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior in Berlin at NW 7, Unter den Linden 72/74. From 1936 to 1941, it consisted of two offices: Command Department (Kommandoamt), responsible for finance, personnel and medical; and the Office of Administration and Law (Verwaltung), responsible for handling all administrative police, legal and economic tasks of the entire Order Police. In 1941, the Colonial Office, the Office of Fire Brigades, and the Office of Technical Emergency Aid were added.[21]

While the Order Police was initially commanded by Kurt Daluege, in May 1943, he had a massive heart attack and was removed from duty.[22] He was replaced by Police and Waffen-SS General Alfred Wünnenberg, who had previously spent his career as a professional police officer.[23]

Branches of police

[edit]

The administration police (Verwaltungspolizei) was the branch with overall command authority for all Orpo police stations. The Verwaltungspolizei also was the central office for record keeping and was the command authority for civilian law enforcement groups, which included the Gesundheitspolizei (health police), Gewerbepolizei (commercial or trade police), and the Baupolizei (building police). In the main towns, Verwaltungspolizei, Schutzpolizei and Kriminalpolizei would be organised into a police administration known as the Polizeipräsidium or Polizeidirektion, which had authority over these police forces in the urban district. Generally speaking, there were three subtypes of uniformed police forces within the Order Police, arranged according to the population size and density of the community they served."[24] These were:

- Gendarmerie (rural police), who were tasked with frontier law enforcement to include small communities, rural districts, and mountainous terrain.

- Municipal protection police (Gemeindepolizei) municipal uniformed police in smaller and some large towns.

- State protection police (Schutzpolizei), state uniformed police in cities and most large towns, which included police-station duties (Revierdienst) and barracked police units for riots and public safety (Kasernierte Polizei).

Inspectors of the Order Police in various branches were established in September 1936, overseeing the entire Order Police within their jurisdictions. At the start of the war, they were gradually renamed "Commanders of the Order Police" (BdO) and given greater authority, directly reporting to Higher SS and Police Leaders.[25] Although fully integrated into the Ordnungspolizei-system, its police officers were still considered municipal civil servants. The civilian law enforcement in towns with a municipal protection police was not performed by the Verwaltungspolizei, but by municipal civil servants. Until 1943, they also had municipal criminal investigation departments, but that year, all such departments with more than 10 detectives were integrated into the Kripo.

The traffic police (Verkehrspolizei) were members of the traffic-law enforcement agency and road safety administration of Germany. Members of this organisation patrolled Germany's roads (other than motorways which were controlled by Motorized Gendarmerie) and responded to major accidents. The Verkehrspolizei was also the primary escort service for high-ranking Nazi leaders who traveled great distances by automobile. Then there was the fire protection police (Feuerschutzpolizei), which consisted of all professional fire departments under a national command structure.

Additional assistance in the macabre atrocities associated with the Eastern Front came from the auxiliary police of the Schutzmannschaft; these were collaborationist auxiliary forces in occupied Eastern Europe.[26]

Hilfspolizei sub-elements

[edit]The Order Police Hauptamt also had authority over the Freiwillige Feuerwehren, the local volunteer civilian fire brigades. At the height of the Second World War, in response to heavy bombing of Germany's cities, the combined Feuerschutzpolizei and Freiwillige Feuerwehren numbered nearly two million members. There was also the air-raid protection police (Luftschutzpolizei), which was part of the civil protection service in charge of air raid defence and rescue victims of bombings in connection with the Technische Nothilfe (Technical Emergency Service) and the Feuerschutzpolizei (professional fire departments). Created as the Security and Assistance Service (Sicherheits und Hilfsdienst) in 1935, it was renamed Luftschutzpolizei in April 1942.[b] Volunteer fire departments conscripted personnel and industrial fire departments were auxiliary police subordinated to the Ordnungspolizei.

Beyond these organizations there was a "radio protection" (Funkschutz) element, which was made up of SS and Orpo security personnel assigned to protect German broadcasting stations from attack and sabotage. The Funkschutz was also the primary investigating service that attempted to detect illegal reception of foreign radio broadcasts among the civilian population. Additional urban and rural emergency police (Stadt- und Landwacht) were created in 1942 as a part-time police reserve, but were abolished in 1945 with the creation of the Volkssturm.

Other police forces

[edit]Additional police units not entirely subordinate to the Hauptamt Ordnungspolizei or the Reich Security Main Office existed across Germany, which made them outside the regular Nazi police structure and were "staffed mainly by officials from the police and judiciary who had served under Weimar".[27][c] Despite the seeming independence of these other functional policing and public safety organizations, they were still part of the Nazi state, which was monitored and controlled by the SS and its subordinated agencies.

Police battalions

[edit]Invasion of Poland

[edit]

Between 1939 and 1945, the Ordnungspolizei maintained military formations, trained and outfitted by the main police offices within Germany.[28] Specific duties varied widely from unit to unit and from one year to another.[29] Generally, the Order Police were not directly involved in frontline combat, except for Ardennes in May 1940, and the Siege of Leningrad in 1941.[30] The first 17 battalion formations (from 1943 renamed SS-Polizei-Bataillone) were deployed by Orpo in September 1939 along with the Wehrmacht army in the invasion of Poland.[31] The battalions guarded Polish prisoners of war behind the German lines, and carried out expulsion of Poles from Reichsgaue under the banner of Lebensraum.[32] They also committed atrocities against both the Catholic and the Jewish populations as part of those "resettlement actions".[33] After hostilities had ceased, the battalions – such as Reserve Police Battalion 101 – took up the role of security forces, patrolling the perimeters of the Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Poland (the internal ghetto security issues were managed by the SS, SD, and the Criminal Police, in conjunction with the Jewish ghetto administration).[34]

Each battalion consisted of approximately 500 men armed with light infantry weapons.[35] In the east, each company also had a heavy machine-gun detachment.[36] Administratively, the Police Battalions remained under the Chief of Police Kurt Daluege, but operationally they were under the authority of regional SS and Police Leaders (SS- und Polizeiführer), who reported up a separate chain of command directly to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.[37] The battalions were used for various auxiliary duties, including the so-called anti-partisan operations, support of combat troops, and construction of defence works (i.e. Atlantic Wall).[38]

Some of them were focused on traditional security roles as an occupying force, while others were directly involved in actions designed to inflict terror and in the ensuing Holocaust.[39] While they were similar to Waffen-SS, they were not part of the thirty-eight Waffen-SS divisions, and should not be confused with them, including the national 4th SS Polizei Panzergrenadier Division.[38] The battalions were originally numbered in series from 1 to 325, but in February 1943 were renamed and renumbered from 1 to about 37, to distinguish them from the Schutzmannschaft auxiliary battalions recruited from local population in German-occupied areas.[38]

Invasion of the Soviet Union

[edit]

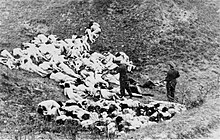

The Order Police battalions, operating both independently and in conjunction with the Einsatzgruppen, became an integral part of the Final Solution in the two years following the attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Operation Barbarossa. The first mass-murder of 3,000 Jews by Police Battalion 309 occurred in occupied Białystok on 12 July 1941.[40] Police battalions were part of the first and second wave of murders in 1941 and into 1942 throughout the territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union and also earlier, during the killing operations within the 1939 borders of the USSR—whether as part of Order Police regiments, or as separate units reporting directly to the local SS and Police Leaders.[41] They included the Reserve Police Battalion 101 from Hamburg, Battalion 133 of the Nürnberg Order Police, Police Battalions 45, 309 from Köln, 91 and 316 from Bottrop-Oberhausen.[40] These units—among others—carried out extensive murder operations across the Eastern Front.[42] In the immediate aftermath of World War II, this latter role was obscured both by the lack of court evidence and by deliberate obfuscation, while most of the focus was on the better-known Einsatzgruppen ("Operational groups") who reported to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) under Reinhard Heydrich.[43]

Order Police battalions involved in direct killing operations were responsible for at least 1 million murders.[44] Starting in 1941 the Battalions and local Order Police units helped to transport Jews from the ghettos in both Poland and the USSR (and elsewhere in occupied Europe) to the concentration and extermination camps, as well as operations to hunt down and murder Jews outside the ghettos.[45] The Order Police were one of the two primary sources from which the Einsatzgruppen drew personnel in accordance with manpower needs (the other being the Waffen-SS).[46]

In 1942, the majority of the police battalions were re-consolidated into thirty SS and Police Regiments. These formations were intended for garrison security duty, anti-partisan functions, and to support Waffen-SS units on the Eastern Front. Notably, the regular military police of the Wehrmacht (Feldgendarmerie, Feldjägerkorps, and Geheime Feldpolizei) were separate from the Ordnungspolizei.

Waffen-SS Police Division

[edit]

The militarization of the police during the war was reflected in the restructuring of police units, with companies replacing traditional formations.[47] In October 1939, a Police Division of 15,800 militarily trained personnel was formed, initially part of the police but made available to the Wehrmacht, participating in the 1940 Western Campaign and later restructured as the SS Polizei Division officially integrated into the Waffen-SS in 1942.[48][d] Many members of the Ordnungspolizei, along with other reservists and men from the Allgemeine SS were organized into the SS Totenkopfdivision.[50] In 1940, the SS Polizei Division was stationed along the Maginot Line to provide passive defense and in preparation for the Nazi invasion of France.[51] Eventually the SS Polizei Division was called into offensive action, when on June 9 and June 10, the 1st and 2nd Police Regiments participated in the assault across the Aisne River and the Ardennes Canal where they faced fierce French resistance before the 2nd Police Regiment broke through and took the town of Voncq.[52] The unit was then ordered to advance through the Argonne Forest and again, despite fierce French fighting, managed to capture Les Islettes.[53] Their efforts notwithstanding, the SS Polizei Division was take out of front-line fighting and placed in reserve near Bar le Duc, but not before they had suffered some 704 casualties in two engagements.[54]

Orpo and SS relations

[edit]

By the start of the Second World War in 1939, the SS had effectively gained complete operational control over the German Police, although outwardly the SS and Police still functioned as separate entities. The Ordnungspolizei maintained its own system of insignia and Orpo ranks as well as distinctive police uniforms. Under an SS directive known as the "Rank Parity Decree", policemen were highly encouraged to join the SS and, for those who did so, a special police insignia known as the SS Membership Runes for Order Police was worn on the breast pocket of the police uniform.

In 1940, standard practice in the German Police was to grant equivalent SS rank to all police generals. Police generals who were members of the SS were referred to simultaneously by both rank titles – for instance, a Generalleutnant in the Police who was also an SS member would be referred to as SS Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Polizei. In 1942, SS membership became mandatory for police generals, with SS collar insignia (overlaid on police green backing) worn by all police officers ranked Generalmajor and above.

The distinction between the police and the SS had virtually disappeared by 1943 with the creation of the SS and Police Regiments, which were consolidated from earlier police security battalions. SS officers now routinely commanded police troops and police generals serving in command of military troops were granted equivalent SS rank in the Waffen-SS. In August 1944, when Himmler was appointed Chef des Ersatzheeres (Chief of the Home Army), all police generals automatically were granted Waffen-SS rank because they had authority over the prisoner-of-war camps.

Ideology

[edit]By 1935, there was a significant shift with increased national political curricula and intensive ideological training by the "Comradeship of the German Police" (Kameradschaftsbund der deutschen Polizei).[55] Monthly national political lectures were instituted, and all police officers were encouraged to attend courses in state and party training facilities.[55]

In keeping with Nazi ideological programmatic lines, the Order Police, alongside the SS, played a key role in implementing Nazi racial policies. Unlike the SS, whose members voluntarily aligned with its ideology, the police required extensive ideological training to adopt and support the SS's goals, which was generally accepted due to a combination of Nazi propaganda, latent antisemitism, and a societal disposition towards authority.[56]

Within the administrative organ (Verwaltungspolizei) for instance, the Order Police were required to read specific history books and essays on Nazi ideology, which were integrated into their practical police training and exams, ensuring alignment with Nazi goals.[57] Training for State Protection Police (Schutzpolizei) at the Berlin-Schöneberg School in 1937 included 44 weekly hours focused on police and criminal law, with two hours dedicated to national politics and ideological training by SS instructors. Similarly, the curriculum included history and National Socialist ideology.[58] From the end of 1942 to the end of 1944, the Mariaschein Police School (later moved to Heidenheim) conducted monthly ideological training sessions for the Schutzpolizei with corresponding training of like-kind being held at other police and police weapons schools across Nazi occupied Europe.[59]

See also

[edit]- Executions in Warsaw's police district

- Ranks and insignia of the Ordnungspolizei

- Police Long Service Award

- Glossary of Nazi Germany

- Schutzmannschaft, auxiliary policemen raised from local populations in occupied Eastern Europe during World War II

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ As early as 1937, the Order Police were already authorized to wear the SS runes on their uniforms.[15]

- ^ The air raid network was supported by the Reichsluftschutzbund (Reich Association for Air Raid Precautions) an organisation controlled from 1935 by the Air Ministry under Hermann Göring. The RLB set up an organisation of air raid wardens who were responsible for the safety of a building or a group of houses.

- ^ Such elements in Nazi Germany included: the "Railway Criminal Investigative Service" (Reichsbahnfahndungsdienst), and the "Railway Protection Police" (Bahnschutzpolizei)—both subordinate to the Deutsche Reichsbahn; the "Postal Protection" (Postschutz) element, comprised by roughly 45,000 members tasked with the security of Germany's mail and other communications' media such as the telephone and telegraph systems; the "Forest Protection Service", (Forstschutzkommando); the "Game Warden/Hunting Police" element (Jagdpolizei); the "Customs & Border Guards" (Zollgrenzschutz) under the Finance Ministry; the "Agricultural Field Police" (Flurschutzpolizei); the "Factory Protection Police" (Werkschutzpolizei)—its personnel were civilians employed by industrial enterprises, and typically were issued paramilitary uniforms; the "Dam and Dyke Police" (Deichpolizei), subordinated to the Ministry of Economy; and the "Harbor Police" (Hafenpolizei) under the Ministry of Transport.

- ^ Additional ideological training was introduced within the division, and approximately 8,000 members of the Orpo's Field Gendarmerie were assigned to the Wehrmacht as military police.[49]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Müller-Hillebrand 1969, p. 322.

- ^ a b c Robertson 2008.

- ^ Showalter 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ Browning 2001, p. 97.

- ^ USHMM, "German Police, 1933–1939".

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 158–162.

- ^ Westermann 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, p. 172.

- ^ Weale 2012, pp. 140–144.

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 783.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 204–213.

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 210–240.

- ^ a b Longerich 2012, p. 250.

- ^ Krausnick 1968, pp. 50–53, 63–66.

- ^ Browning 2000, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Browning 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Browning 1992, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 4.

- ^ "EHRI - Hauptamt Ordnungspolizei".

- ^ McKale 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 149.

- ^ USHMM, "The Order Police".

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 587 fn.

- ^ Harten 2018, pp. 327–330.

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 150, 162.

- ^ Goldhagen 1997, p. 204.

- ^ Goldhagen 1997, p. 186.

- ^ Browning 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Browning 2001, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Browning 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Rossino 2003, pp. 69–72.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 81.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Browning 2001, p. 45.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b c U.S. War Dept. 1995, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Browning 2001, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Browning 2001, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, pp. 175, 192–198.

- ^ Westermann 2005, pp. 174–177, 195, 220–225.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, pp. 100–106.

- ^ Goldhagen 1997, pp. 202, 271–273.

- ^ Goldhagen 1997, p. 195.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 307.

- ^ Harten 2018, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 308.

- ^ Stein 1984, p. 33.

- ^ Stein 1984, p. 57.

- ^ Stein 1984, p. 87.

- ^ Stein 1984, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Stein 1984, p. 88.

- ^ a b Harten 2018, p. 171.

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 11.

- ^ Harten 2018, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 204.

- ^ Harten 2018, p. 348.

Bibliography

[edit]- Browning, Christopher R. (2000). Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52177-299-0.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2001) [1992]. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14100-042-8.

- Buchheim, Hans (1968). "The SS – Instrument of Domination". In Krausnick, Helmut; Buchheim, Hans; Broszat, Martin; Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf (eds.). Anatomy of the SS State. New York: Walker and Company. pp. 127–301. ISBN 978-0-00211-026-6.

- Goldhagen, Daniel (1997). Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0679772685.

- Harten, Hans-Christian (2018). Die weltanschauliche Schulung der Polizei im Nationalsozialismus (in German). Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-50678-836-8.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 0-8419-0910-5.

- Krausnick, Helmut (1968). "The Persecution of the Jews". In Krausnick, Helmut; Buchheim, Hans; Broszat, Martin; Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf (eds.). Anatomy of the SS State. New York: Walker and Company. pp. 3–124. ISBN 978-0-00211-026-6.

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19959-232-6.

- McKale, Donald M (2011). Nazis after Hitler: How Perpetrators of the Holocaust Cheated Justice and Truth. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-1316-6.

- Müller-Hillebrand, Burkhart (1969). Der Zweifrontenkrieg: Das Heer vom Beginn des Feldzuges gegen die Sowjetunion bis zum Kriegsende. Das Heer (1933–1945). Vol. 3. Frankfurt am Main: Mittler. OCLC 83882908.

- Robertson, Struan (2008). "Hamburg Police Battalions during the Second World War". University of Hamburg (via Wayback Machine). Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on February 22, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- Rossino, Alexander B. (2003). Hitler Strikes Poland: Blitzkrieg, Ideology, and Atrocity. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 978-0-70061-234-5.

- Showalter, Dennis (2005). "Foreword". Hitler's Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. Kansas City: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1724-1.

- Stein, George (1984) [1966]. The Waffen-SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War 1939–1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- USHMM. "The Nazification of the German Police, 1933–1939". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum—Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- USHMM. "The Order Police". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum—Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- U.S. War Dept. (1995) [March 1945]. David I. Norwood (ed.). Handbook on German Military Forces. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2011-1.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York; Toronto: NAL Caliber (Penguin Group). ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

- Westermann, Edward B. (2005). Hitler's Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. Kansas City: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1724-1.

- Williams, Max (2001). Reinhard Heydrich: The Biography, Volume 1—Road To War. Church Stretton: Ulric Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9537577-5-6.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: MacMillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-897500-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. II. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Nix Philip and Jerome Georges (2006). The Uniformed Police Forces of the Third Reich 1933-1945, Leandoer & Ekholm. ISBN 91-975894-3-8