Persian mythology

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

|---|

Iranian mythology, or Persian mythology in western term (Persian: اسطورهشناسی ایرانی), is the body of the myths originally told by ancient Persians and other Iranian peoples and a genre of ancient Persian folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of deities, heroes, and mythological creatures, and the origins and significance of the ancient Persians' own cult and ritual practices. Modern scholars study the myths to shed light on the religious and political institutions of not only Iran but of the Persosphere, which includes regions of West Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, and Transcaucasia where the culture of Iran has had significant influence. Historically, these were regions long ruled by dynasties of various Iranian empires,[note 1][1][2][3] that incorporated considerable aspects of Persian culture through extensive contact with them,[note 2] or where sufficient Iranian peoples settled to still maintain communities who patronize their respective cultures.[note 3] It roughly corresponds to the Iranian Plateau and its bordering plains.[4][5]

The Encyclopædia Iranica project uses the term Iranian cultural continent for this region.[6][7]

Religious background

[edit]Most characters in Persian mythology are either good or evil. The resultant discord mirrors the nationalistic ideals of the early Islamic era as well as the moral and ethical perceptions of the Zoroastrian period, in which the world was perceived to be locked in a battle between the destructive Ahriman and his hordes of demonic Divs and their Aneran supporters, versus the Creator Ahura Mazda, who although not participating in the day-to-day affairs of mankind, was represented in the world by the izads and the righteous ahlav Iranians. The only written texts relating to religious come from prophet Zoroaster, initiated the reforms which would become Zoroastrianism.

Good and Evil

[edit]Iranian mythology is based on the battle between good and evil. Indo-Iranian peoples believed in two general categories of gods: Ahuras, and evil: Divan. The characteristics of these two ranks of gods among Iranians and Hindus, and were transformed into each other, in the sense that among Indians Ahuras became evil and Divan became good, And among Iranians, Ahuras became good and Divan became evil. They sacrificed for both types of gods. The purpose of the sacrifice for the evil gods was to pay them a ransom to stop killing people. Sacrifice was made for good gods to seek help and blessing from them. On the other side of the fence is Zahhak, a symbol of despotism who was, finally, defeated by Kāve, who led a popular uprising against him. Zahhak (Avestan: Aži Dahāka) was guarded by two vipers which grew out from both of his shoulders. No matter how many times they were beheaded, new heads grew on them to guard him. The snake, like in many other mythologies, was a symbol of evil, but many other animals and birds appear in Iranian mythology, and, especially, the birds were signs of good omens. Most famous of these is the Simurgh, a large, beautiful, and powerful bird; and the Huma bird, a royal bird of victory whose plume adorned Persian crowns. Peri (Avestan Pairika), a beautiful albeit evil woman in early mythology, gradually became less evil and more beautiful. The conflict between good and evil is prevalent in Persian myths as well as Zoroastrianism.

Development

[edit]

Before the Medes, Aryan civilizations lived in this land, which mostly had no linguistic, racial, or even religious kinship with their neighbors outside the Iranian plateau, and sometimes they had solidarity. These tribes included Lullubi, Gutian, Kassites, and Urartu. The Elamites also had an old and well-known civilization in the southwest of the Iranian plateau, but they were not of the Aryan race. These tribes, who controlled the southern half of Iran, the west and the northwest, had their own special myths. Not much is known about their mythology. However, Kassites mythology has some similarities with later Iranian civilizations, namely the Medes and Persians, especially in the names. The mythology of the Elamites, who were a separate people and had linguistic affinities with the non-Aryans of India, shares some myths contained in the Rigveda. The traditions and beliefs of these people influenced the beliefs of their later society, which was under the cultural domination of the Aryans. With the power of the Medes and then the Persians, a newer mythology, known as the comprehensive mythology of Iran, began. Researchers believe that before the power of the Medes, a branch of Aryans migrated from Iran to India. That is why the ancient forms of Indian mythology are very similar to the ancient forms of Iranian mythology. The mythology of Iran was greatly influenced by the myths of the native peoples of the Iranian plateau and the myths of the Middle River. Researchers have shown these influences in many places in Iranian mythology. Indian and Iranian mythology are close in many ways. This proximity is sometimes to the extent of the similarity of the names of persons and places. The close languages of these two groups also confirm their common roots; Therefore, the origin of the mythology of these two nations has been the same in the distant past, but the migration of Indians from the Aryan plateau to lands with different nature and climatic conditions, as well as indigenous peoples, has brought about fundamental changes in their mythology and religious beliefs. There are good and evil forces in both of these myths. The names of their gods are close to each other. Fire is sacred and praised in Iranian and Indian beliefs, and they used to perform sacrifices for the gods in a similar manner. The oldest examples of the ancient form of Iranian mythology are references in Avesta, especially in Yashta. Because Yashta are above all a collection of prayer hymns, there are no detailed references to myths in them. Everything is closed and short. The most detailed texts about Iranian mythology are in Zoroastrian writings in Middle Persian. The final compilation of most of them is in the early Islamic era; But most of them are based on the texts of the late Sasanian period. Some of the most famous of these books are Bundahisn, Denkard and the Vendidad. The other major source for Persian mythology is the Shahnameh (“The Book of Kings”) written by the Persian poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi (940-1020 CE).

Overview of the world

[edit]In the mythological beliefs of Iranians before Zoroastrian, the world was round and flat like a plate. The sky was also imagined as stone and hard as a diamond. The earth in the center was completely flat and untouched, and there was no movement between the earth, the moon, and the stars. But everything changed by Ahura Mazda. The dynamism arose, the mountains were created, the rivers flowed, and the moon and stars began to rotate. In the general picture of the world at that time, the world was divided into seven regions, the center of which was called Khoonirth, and six satellite lands were around it. The sky had three levels of star base, moon base and sun base. Dark Mountain, which was located in Alborz, was considered the center of the universe. The message of Iranian myths is the confrontation of two gems of good and evil. One is truth and the other is untruth, one is fragrant and the other is bright, one is light and the other is darkness. In fact, serving good concepts is still one of the great mythological messages of Iran.

Evil Forces

[edit]

In Iranian mythology, what can be seen everywhere in all mythological narratives is the presence of evil and evil forces in the world. These evil forces, which are considered to be the assistants of Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), are mentioned by the names of Div and Druq. These two have male and female genders, and against every good thing in the world. In Iranian mythology, the world is always the scene of conflict between these evil and good forces.

Ahura Mazda and Ahriman

[edit]Ahura Mazda and Ahriman have been at war with each other since eternity, and life in the world is a reflection of the cosmic struggle of the two. Ahriman's place of residence is the north of the earth, where the whole divan of "Zeed and Islah". Ahriman appears in 3 forms other than his image: Chelpasa (lizard), Snake and Young. Although he is mentioned in the Shahnameh of the Mardosh kingdom, in the Avesta he is a three-headed, six-eyed and three-nosed demon with a body full of scorpions. However, based on Zoroastrian writings, in the final days of the world, it is Ahura Mazda who will win over Ahriman and destroy him forever, and after that only goodness, light and health will remain in the world.

Myths of creation and the end of the world

[edit]

Creation takes place within twelve thousand mythological years. These twelve thousand years are divided into four periods of three thousand years. The first three thousand years begins with the birth of two children named Ahura Maza and Ahriman from Zarvan. In the first three thousand years, the world is Minoan and there is still neither place nor time. In this period, two entities are mentioned. One is the world belonging to Ahura Maza, which is full of light, life, knowledge, beauty, and fragrance, and the second is the world belonging to Ahriman, which is dark, ugly, smelly, and full of sorrow and disease. Ahura Maza first creates Amesha Spenta, which are: Sepand Mino, Khordad, Mordad, Bahman, Ordibehesht, Shahrivar and Spandarmad. After the creation of Amshaspandan, Ahura Mazda creates the gods. Ahriman also creates Sardivan for each of Amshaspandans to deal with Ahura Maza. At the end of the first three thousand years, a peace is made between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman that the last battle between the forces of evil and good will take place nine thousand years later. After the pact is concluded, Ahura Mazda utters the true prayer, Ahunur, and as a result, Ahriman falls to hell and remains unconscious there for the second three thousand years.

The second three thousand years: After Ahriman's unconsciousness, Ahura Mazda begins the creation of the world. He creates the sky, water, earth, plants, animals and humans in one year. The anniversary of these creations are six festivals, which are known as Gahambars. The main prototypes of creation are the cow, four-legged animals, and the human beings. At the end of the second three thousand years, Ahriman, with the help of his allies, returns and decides to destroy the current world.

The third three thousand years: in this period, we see the conflict of Ahriman and his demons with Ahura Maza and his gods. Meanwhile, Ahriman kills the created cow, grains, plants and animals are created. After 40 years, a rhubarb branch grows from the seed of Keyumars, which has two stalks and fifteen leaves. These fifteen leaves are in accordance with the years that Mishiyeh and Mishyaneh, the first Adam couple have at that time. Mishiyeh is male and Mishyaneh is female. Mishiyeh is known as the father of humans and Mishyaneh as the mother of humans. Ahriman attacks their thoughts and they utter the first lie and attribute creation to Ahriman. They both repent and have seven pairs of children and die after living for a hundred years. The genealogy of the descendants of Mishiyeh and Mishyaneh includes the origins of many different races. The Iranian race is from a couple called Siamak and Neshak. After them, Farag-Farwagin and after them the couple Hushang and Guzak are born.

The fourth three thousand years: The third three thousand years ends in the middle of the era of Kay Lohrasp. The most important feature of this period is the emergence of Zoroaster. This period is the period of religious revelation. Ahura Mazda reveals the secrets of religion to Zoroaster, and he declares himself a prophet of Zoroastrianism religion and his mission. Mazdaism is a religion that has Ahura Mazda at the head of their gods, and in other words, it is Zoroastrian religion. After Zoroaster's death, Oshidar, Oshidar Mah and Saoshyant take over the leadership of Behdinan. Sushyant period is the period of evolution of Urmazdi creatures, and all divans from the generation of bipeds and quadrupeds are destroyed. Sushyant has the task of raising the dead. Each of these dead people pass through the Chinvat Bridge.

Mythological history of Iran

[edit]Pishdadian dynasty: Pishdadians are the first dynasty of Iranian history according to mythological texts, which are related to Kay Lohrasp. This series of kings who brought the beginning of human civilization to Iranians and were able to record fire and use of metals and other living things and capturing the court in their records. It starts from Kay Lohrasp and ends at Garshasp. However, all these are mythological characters in the Avesta, and in the Zoroastrian texts of the Sasanian period, they are gods of the Izder race.

Kayanian dynasty: The Kayanians are the second mythological dynasty of Iran, which in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh is equal to the epic periods. It starts with Kay Kawad and ends with the possessors. In this period, Zoroastrian religion is presented and we see fundamental changes in the mythological history of Iran. The most important events of this period are related to Iran and Turan wars. The story of Arash belongs to the narratives of this period. In the Shahnameh, it is associated with the epic, and in it Rostam, who is a less prominent character in Zoroastrian texts, rises to the top. These kings were probably considered the local kings of eastern Iran. Al-Biruni has compared the Achaemenids to the Kayanians in his works. However, it is clear that the last Kiyan king who is defeated by Alexander in mythological texts is the same Darius III of Achaemenid.

A fusion of mythological history and real history: This period corresponds to the time when the Iranian mythological narrative coincides with concrete historical data such as stone inscriptions and Greek texts; It means the fall of Iran at the hands of Alexander. However, the Iranian narrative considered the reign of Alexander and the Greeks to be very short, and did not assume any time for the Seleucids, it also estimated the period of 450 years of rule of the Parthians to be only 200 years. The final data of the Parthian era in Iranian mythology deals with the battle between Artabanus IV and Ardeshir I, which is the same as what was found in Latin and Armenian texts. After that, the Sassanid period begins, and they are introduced as descendants of the Kayanians.

Life & Afterlife

[edit]The one who chose to follow Ahura Mazda, would live a good life with others, and the one who chose Ahriman, will become a source of strife. Death is a journey to the afterlife, and the soul of the dead person has to cross the Chinvat Bridge. Good souls found the bridge to be a wide road leading to heaven, and for bad souls who chose to follow Ahriman during their life, they fell from the bridge into hell.

Gods

[edit]

- Ahura Mazda: the creator deity and god of the sky. He is the first and most frequently invoked spirit in the Persian mythology. The literal meaning of the word Ahura is "lord", and that of Mazda is "wisdom".

- Angra Mainyu (Ahriman): the "destructive/evil spirit" and the main adversary in Zoroastrianism either of the Spenta Mainyu, the "holy/creative spirits/mentality", or directly of Ahura Mazda.

- Mithra: The god of covenants, light, oath, justice, the sun, contracts, and friendship. Mithra is also a judicial figure, an all-seeing protector of Truth, and the guardian of cattle, the harvest, and the Waters. The Romans attributed their Mithraic mysteries to Zoroastrian Persian sources relating to Mithra. Since the early 1970s, the dominant scholarship has noted dissimilarities between the Persian and Roman traditions, making it, at most, the result of Roman perceptions of Zoroastrian ideas.

The Lotus flower is the symbol of goddess Anahita. - Anahita: goddess and appears in complete and earlier form as Aredvi Sura Anahita, associated with fertility, healing and wisdom. There is also a temple named Anahita in Iran. The symbol of goddess Anahita is the Lotus flower. Lotus Festival (Persian: Jashn-e Nilupar) is an Iranian festival that is held on the end of the first week of July. Holding this festival at this time was probably based on the blooming of lotus flowers at the beginning of summer.

- Rashnu: Rashnu is one of the three judges who pass judgment on the souls of people after death. Rashnu's standard appellation is "the very straight." The 18th day of every month in the Zoroastrian calendar is dedicated to Rashnu. The Counsels of Adarbad Mahraspandan, a Sassanid-era text, notes that on the 18th day "life is merry".

- Verethragna: The neuter noun verethragna is related to Avestan verethra, 'obstacle' and verethragnan, 'victorious'. Representing this concept is the divinity Verethragna, who is the hypostasis of "victory", and "as a giver of victory Verethragna plainly enjoyed the greatest popularity of old.

Verethragna on the coinage of Kanishka I, 2nd century CE - Vayu-Vata: divinity of the wind (Vayu) and of the atmosphere (Vata). The names are also used independently of one another, with 'Vayu' occurring more frequently than 'Vata', but even when used independently still representing the other aspect. The entity is simultaneously angelic and demonic, that is, depending on the circumstances, either yazata - "worthy of worship" - or daeva, which in Zoroastrian tradition is a demon. Scripture frequently applies the epithet "good" when speaking of one or the other in a positive context.

- Tishtrya: benevolent divinity associated with life-bringing rainfall and fertility. Tishtrya is Tir in Middle- and Modern Persian. In the Zoroastrian religious calendar, the 13th day of the month and the 4th month of the year are dedicated to Tishtrya/Tir, and hence named after the entity. In the Iranian civil calendar, which inherits its month names from the Zoroastrian calendar, the 4th month is likewise named Tir.

- Atar: Zoroastrian concept of holy fire, sometimes described in abstract terms as "burning and unburning fire" or "visible and invisible fire". It is considered to be the visible presence of Ahura Mazda and his Asha through the eponymous Yazata. The rituals for purifying a fire are performed 1,128 times a year.

- Haoma: a divine plant in Zoroastrianism and in later Persian culture and mythology. Haoma has its origins in Indo-Iranian religion and is the cognate of Vedic soma.

- Zorvan: Zurvan was perceived as the god of infinite time and space and also known as "one" or "alone." Zurvan was portrayed as a transcendental and neutral god without passion; one for whom there was no distinction between good and evil. The name Zurvan is a normalized rendition of the word, which in Middle Persian appears as either Zurvān, Zruvān or Zarvān. The Middle Persian name derives from Avestan zruvan.

- Spenta Armaiti: Spenta Armaiti is the guardian and goddess of the green earth and a sign of fertility and birth.

Creatures

[edit]

- Simurgh: a benevolent bird. It is sometimes equated with other mythological birds such as the phoenix, and the humā, though it must be understood as a completely different mythological creature of its own. The figure can be found in all periods of Iranian art and literature and is also evident in the iconography of Georgia, medieval Armenia, the Eastern Roman Empire, and other regions that were within the realm of Persian cultural influence.

- Chamrosh: a bird said to live on the summit of Mount Alborz, described as having the body of a dog/wolf with the head and wings of an eagle. It was said to inhabit the ground beneath the soma tree that was the roost of the Senmurv. When the Senmurv descended or alighted from its roost, all the ripened seeds fell to the earth. These seeds were gathered by the Chamrosh, which then distributed them to other parts of the earth. Chamrosh is the archetype of all birds, said to rule and protect all avifauna on Earth. According to the Avesta, Iran is pillaged every three years by outsiders, and when this happens, the angel Burj sends Chamrosh out to fly onto the highest mountaintop then snatch the pillagers in its talons as a bird does corn.

Huma bird at Persepolis (550-330 BC) - Huma: is a mythical bird, continuing as a common motif in Sufi and Diwan poetry. Although there are many legends of the creature, common to all is that the bird is said never to alight on the ground, and instead to live its entire life flying invisibly high above the earth. Huma bird is said to never come to rest, living its entire life flying invisibly high above the earth, and never alighting on the ground (in some legends it is said to have no legs). In several variations of the Huma myths, the bird is said to be phoenix-like, consuming itself in fire every few hundred years, only to rise anew from the ashes. The Huma bird is said to have both the male and female natures in one body, each nature having one wing and one leg. Huma is considered to be compassionate, and a 'bird of fortune' since its shadow is said to be auspicious. In Sufi tradition, catching the Huma is beyond even the wildest imagination, but catching a glimpse of it or even a shadow of it is sure to make one happy for the rest of one's life. It is also believed that Huma cannot be caught alive, and the person killing a Huma will die in forty days.

- Al: a class of demon. Als are demons of childbirth, interfering with human reproduction.

- Khrafstra: a cover term in Zoroastrianism for the animals that are harmful or repulsive. They were considered creations of the Evil Spirit Angra Mainyu and killing them was seen as meritorious. In the Young Avesta and Middle Persian texts, the class of xrafstars includes frogs, reptiles, scorpions and insects like ants or wasps, whereas predators such as the wolf are not referred to as xrafstars, even though they too are considered to be creations of evil. Herodotus narrates about the practice of killing xrafstars among the Magi: "The Magi are a very peculiar race, different entirely from the Egyptian priests, and indeed from all other men whatsoever. The Egyptian priests make it a point of religion not to kill any live animals except those which they offer in sacrifice. The Magi, on the contrary, kill animals of all kinds with their own hands, excepting dogs and men. They even seem to take a delight in the employment, and kill, as readily as they do other animals, ants and snakes, and such like flying or creeping things"

- Jinn: invisible creatures in early religion in pre-Islamic era and later in Islamic culture and beliefs. Like humans, they are accountable for their deeds and can be either believers (Muslims) or unbelievers (kafir), depending on whether they accept God's guidance. Since jinn are neither innately evil nor innately good, Islam acknowledged spirits from other religions and was able to adapt them during its expansion. Jinn are not a strictly Islamic concept; they may represent several pagan beliefs integrated into Islam.

Peri, flying, with cup and wine flask. - Peri: exquisite, winged spirits renowned for their beauty. They are described in one reference work as mischievous beings that have been denied entry to paradise until they have completed penance for atonement.

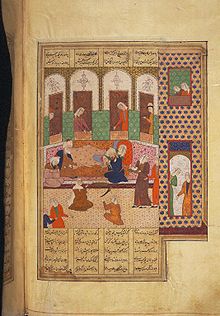

Shahnameh, The Akvan Div throws Rostam into the sea. - Div: monstrous creatures within Middle Eastern lore, with Persian origins. They exist along with jinn, peri and shayatin.They are described as having a body like that of a human, only of gigantic size, with two horns upon their heads and teeth like the tusks of a boar. Powerful, cruel and cold-hearted, they have a particular relish for the taste of human flesh. Some use only primitive weapons, such as stones: others, more sophisticated, are equipped like warriors, wearing armour and using weapons of metal. Despite their uncouth appearance – and in addition to their great physical strength – many are also masters of sorcery, capable of overcoming their enemies by magic and afflicting them with nightmares.[8] In Shahnameh, they are already the evil entities endowed with roughly human shape and supernatural powers familiar from later folklore, in which the divs are described as ugly demons with supernatural strength and power, who, nonetheless, may sometimes be subdued and forced to do the bidding of a sorcerer.

- Aeshma: the Younger Avestan name of Zoroastrianism's demon of "wrath." Aeshma is variously interpreted as "wrath," "rage," and "fury." His standard epithet is "of the bloody mace."

- Div-e Sepid: In the Shahnameh, Div-e Sepid (White Demon), is the chieftain of the Divs (demons) of Mazandaran. He is a huge being. He possesses great physical strength and is skilled in sorcery and necromancy. He destroys the army of Kay Kavus by conjuring a dark storm of hail, boulders, and tree trunks using his magical skills. He then captures Kay Kavus, his commanders, and paladins; blinds them, and imprisons them in a dungeon. Rostam undertakes his "Seven Labors" to free his sovereign. At the end, Rostam slays Div-e Sepid and uses his heart and blood to cure the blindness of the king and the captured Persian heroes. Rostam also takes the Div's head as a helmet and is often pictured wearing it.

A manticore (labeled "martigora") by Johannes Jonston (1650). - Manticore: a legendary creature similar to the Egyptian sphinx that proliferated in western European medieval art as well. It has the head of a human, the body of a lion and the tail of a scorpion. There are some accounts that the spines can be launched like arrows. It eats its victims whole, using its three rows of teeth, and leaves no bones behind.

- Azhi (Dragon)

Famous Myths

[edit]

Persian myths is filled with famous heroes, to name a few: the greatest Persian hero is Rostam, who is the grandson of the hero Sām, and son of the equally Zal and Rudaba. Rostam was always represented as the mightiest of Iranian paladins (holy warriors). He rides the legendary stallion Rakhsh and wears a special suit named Babr-e Bayan in battles. In the Shahnameh, Rostam and his predecessors are Marzbans of Sistan. Rostam is best known for his tragic fight with Esfandiyār, the other legendary Iranian hero; for his expedition to Mazandaran (not to be confused with the modern Mazandaran Province); and for tragically fighting and killing his son, Sohrab, without knowing who his opponent is. He is also known for the story of his Seven Labours.

Another great hero is Jamshid (also given as Yama), who rules the world with justice. He is given power by the gods as a reward for his selfless devotion and uses it wisely. In Persian mythology and folklore, Jamshid is described as the fourth and greatest king of the epigraphically unattested Pishdadian Dynasty (before the Kayanian dynasty). Edward FitzGerald transliterated the name as Jamshyd. In the eastern regions of Greater Iran, and by the Zoroastrians of the Indian subcontinent it is rendered as Jamshed

Bahram, is an Iranian hero in Shahnameh. He is son of Goudarz and brother of Rohham, Giv and Hojir. In the story of Siavash, he and Zange-ye Shavaran are Siavash's counselors. They unsuccessfully try to convince Siavash not to go to Turan. When Siavash goes to Turan and abandons Iranian army, Bahram is put in command of the Iranian army until the arrival of Tous. His most important adventure is in the story of Farud, where he fights with Turanian army along with other Iranian heroes.

Rudaba: a Persian mythological female figure in Ferdowsi's epic Shahnameh. She is the princess of Kabul, daughter of Mehrab Kaboli and Sindukht, and later she becomes married to Zal, as they become lovers. They had two children, including Rostam, the main hero of the Shahnameh.

Rostam's Seven Labours: a series of acts carried out by the greatest of the Iranian heroes, Rostam, The story was retold by Ferdowsi in his epic poem, Shahnameh. The Seven Labours were seven difficult tasks undertaken by Rostam, accompanied, in most instances, only by his faithful and sagacious steed Rakhsh, although in two labours he was accompanied also by the champion, Olad.

Rostam and Sohrab: The tragedy of Rostam and Sohrab forms part of the 10th-century Persian epic Shahnameh by the Persian poet Ferdowsi. It tells the tragic story of the heroes Rostam and his son, Sohrab.

Esfandiyār: a legendary Iranian hero and one of the characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh. He was the son and the crown prince of the Kayanian King Goshtasp and Queen Katāyoun. He was the grandchild of Kay Lohrasp. Esfandiyār is best known for the tragic story of a battle with Rostam. It is one of the longest episodes in Shahnameh and is one of its literary highlights.

Vis and Rāmin: a classical Persian love story. The epic was composed in poetry by Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani in the 11th century. Gurgani claimed a Sasanian origin for the story, but it is now regarded as of Parthian dynastic origin, probably from the 1st century AD. It has also been suggested that Gorgani's story reflects the traditions and customs of the period immediately before he himself lived. The framework of the story is the opposition of two Parthian ruling houses, one in the west and the other in the east. Gorgani originally belongs to Hyrcania which is one of main lands of Parthians. The existence of these small kingdoms and the feudalistic background point to a date in the Parthian period of Iranian history. The story is about Vis, the daughter of Shāhrū and Qārin, the ruling family of Māh (Media) in western Iran, and Ramin (Rāmīn), the brother to Mobed Manikan, the King of Marv in northeastern Iran. Manikan sees Shāhrū in a royal gala, wonders at her beauty, and asks her to marry him. She answers that she is already married, but she promises to give him her daughter in marriage if a girl is born to her.

Faramarz: an Iranian legendary hero in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh. He was son of Rostam and at last killed by Kay Bahman. The book Faramarz-nama, written about a hundred years after Shahnameh, is about Faramarz and his wars. He is also mentioned in other ancient books like Borzu Nama.

Iranian mythology in the Islamic period

[edit]

After Islam came to Iran, many Iranian myths were discarded or at least fell out of favor. Myths related to creation, actions of gods and supernatural forces in general, and predictions related to the end of the world are among them. Contrary to the mentioned cases, the deeds of mythological characters were transferred to modern Persian in the form of epics and preserved to a large extent. As the greatest epic work of Iranian history, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh was written in the Islamic era. In terms of literature and epic, Shahnameh has great superiority over all the works of the previous eras. Some Iranians even tried to establish a kind of equivalent relationship between the mythological figures of these two completely different frameworks. So the time, place and mythological characters of the two mythological systems, Iranian and Semitic, were mixed up; For example, in Iranian mythology, the parents of man are Ayudamen (or Meshia) and Meshiani. In the Islamic era, some people equated Ayudamen with Adam, who is the first of the people in Semitic mythology, and it is the same. Along with the intermingling of Iranian and Semitic mythology, which increased with the passage of time, Iranian mythology continued to live and evolve among the Zoroastrian minority. One of the most important developments was the changes that took place in the predictions about the end of time. There were more references to the Tazi raiders and the new religion of the conquerors.

See also

[edit]- Iranian folklore

- Iranian mythology

- List of articles related to Persian mythology

- Persian folklore

- Persian literature

- Proto-Indo-Iranian religion

- Zoroastrianism

Notes

[edit]- ^ These include the Medes, Achaemenids, Parthians, Sasanians, Samanids, Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars).

- ^ For example, those regions and peoples in the North Caucasus that were not under direct Iranian rule.

- ^ Such as in the western parts of South Asia, Bahrain and Tajikistan.

References

[edit]- ^ Marcinkowski, Christoph (2010). Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 83. ISBN 978-3-643-80049-7.

- ^ "Interview with Richard N. Frye (CNN)". Archived from the original on 2016-04-23.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (1962). "Reitzenstein and Qumrân Revisited by an Iranian". The Harvard Theological Review. 55 (4): 261–268. doi:10.1017/S0017816000007926. JSTOR 1508723. S2CID 162213219.

- ^ "IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. Clive Holes. 2001. Page XXX. ISBN 978-90-04-10763-2

- ^ "Columbia College Today". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Sarkhosh-Curtis, V., Persian Myths (1993) London, ISBN 0-7141-2082-0

- ^ "Encyclopædia Iranica", Wikipedia, 2023-11-15, retrieved 2023-12-31

- Iran almanac and book of facts 1964–1965. Fourth edition, new print. Published by Echo of Iran, Tehran 1965.

Further reading

[edit]- Hinnells, J. R. (1985). Persian Mythology. P. Bedrick. ISBN 0872260178.