Rope (film)

| Rope | |

|---|---|

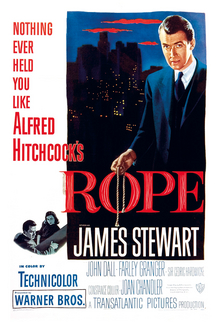

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Screenplay by | Arthur Laurents |

| Story by | Hume Cronyn |

| Based on | Rope by Patrick Hamilton |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph A. Valentine William V. Skall |

| Edited by | William H. Ziegler |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.[N 1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5[3][4]–2 million[5] |

| Box office | $2.2[6]–2.7 million[3] |

Rope is a 1948 American psychological crime thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, based on the 1929 play of the same title by Patrick Hamilton. The film was adapted by Hume Cronyn with a screenplay by Arthur Laurents.[7]

The film was produced by Hitchcock and Sidney Bernstein as the first of their Transatlantic Pictures productions. Starring James Stewart, John Dall and Farley Granger, this is the first of Hitchcock's Technicolor films,[8] and is notable for taking place in real time and being edited so as to appear as four long shots through the use of stitched-together long takes.[9] It is the second of Hitchcock's "limited setting" films, the first being Lifeboat (1944).[10] The original play was said to be inspired by the real-life murder of 14-year-old Bobby Franks in 1924 by University of Chicago students Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

Plot

[edit]Two brilliant young aesthetes, Brandon Shaw and Phillip Morgan, strangle to death their former classmate from prep school, David Kentley, in their Manhattan penthouse apartment. They commit the crime as an intellectual exercise: they want to prove their superiority by committing the "perfect murder".

After hiding the body in a large antique wooden chest, Brandon and Phillip host a dinner party at the apartment, which has a panoramic view of Manhattan's skyline. The guests, who are unaware of what has happened, include the victim's father, Mr. Kentley, and aunt, Mrs. Atwater; his mother is unable to attend because of a cold. Also present are David's fiancée, Janet Walker, and her former lover, Kenneth Lawrence, who was once David's close friend.

Brandon uses the chest containing the body as a buffet table for the food, just before their housekeeper, Mrs. Wilson, arrives to help with the party.

Brandon and Phillip's idea for the murder was inspired years earlier by conversations with their prep-school housemaster, publisher Rupert Cadell. While they were at school, Rupert had discussed with them, in an apparently approving way, the intellectual concepts of Nietzsche's Superman, as a means of showing one's superiority over others. He, too, is among the guests at the party since Brandon, in particular, thinks that he would approve of their "work of art."

Brandon's subtle hints about David's absence indirectly lead to a discussion on the "art of murder." Brandon appears calm and in control, although when he first speaks to Rupert, he is nervously excited and stammering. Phillip, on the other hand, is visibly upset and morose. He does not conceal it well and starts to drink too much. When David's aunt, Mrs. Atwater, who fancies herself a fortune-teller, tells Phillip that his hands will bring him great fame, she refers to his skill at the piano, but he appears to think this refers to the notoriety of being a strangler.

However, much of the conversation focuses on David, whose strange absence worries the guests. A suspicious Rupert quizzes a fidgety Phillip about this and some of the inconsistencies raised in conversation. For example, Phillip vehemently denies ever strangling a chicken at the Shaws' farm, although Rupert has seen Phillip strangle several. Phillip later complains to Brandon about having had a "rotten evening," not because of David's murder, but because of Rupert's questioning.

As the evening goes on, David's father and fiancée begin to worry because he has neither arrived nor phoned. Brandon increases the tension by playing matchmaker between Janet and Kenneth. Mrs. Kentley calls, overwrought because she has not heard from David, and Mr. Kentley decides to leave. He takes with him some books Brandon has given him, tied together with the rope Brandon and Phillip used to strangle his son. When Rupert leaves, Mrs. Wilson accidentally hands him David's monogrammed hat, further arousing his suspicion. Rupert returns to the apartment a short while after everyone else has departed, pretending that he has left his cigarette case behind. He asks for a drink and then stays to theorize about David's disappearance.

He is encouraged by Brandon, who hopes Rupert will understand and even applaud them. A drunk Phillip, unable to bear it anymore, throws a glass and accuses Rupert of playing cat-and-mouse games with him and Brandon. Rupert seizes Brandon's gun from Phillip and insists on examining the chest over Brandon's objections. He lifts the lid of the chest and finds the body inside. He is horrified and ashamed, realizing that Brandon and Phillip used his own rhetoric to rationalize murder. Rupert disavows all his previous talk of superiority and inferiority and fires several shots out the window to attract attention. As the police arrive, Rupert sits on a chair next to the chest, Phillip begins to play the piano, and Brandon continues to drink.

Cast

[edit]-

James Stewart as Rupert Cadell

-

John Dall as Brandon Shaw

-

Farley Granger as Phillip Morgan

-

Joan Chandler as Janet Walker

-

Sir Cedric Hardwicke as Mr. Henry Kentley

-

Constance Collier as Mrs. Anita Atwater

-

Douglas Dick as Kenneth Lawrence

-

Edith Evanson as Mrs. Wilson

-

Dick Hogan as David Kentley

Production

[edit]The film is one of Hitchcock's most experimental and "one of the most interesting experiments ever attempted by a major director working with big box-office names",[11] abandoning many standard film techniques to allow for the long unbroken scenes. Each shot ran continuously for up to ten minutes (the camera's film capacity) without interruption. It was shot on a single set, aside from the opening establishing shot street scene under the credits. Camera moves were carefully planned and there was almost no editing.

The walls of the set were on rollers and could silently be moved out of the way to make way for the camera and then replaced when they were to come back into the shot. Prop men constantly had to move the furniture and other props out of the way of the large Technicolor camera, and then ensure they were replaced in the correct location. A team of soundmen and camera operators kept the camera and microphones in constant motion, as the actors kept to a carefully choreographed set of cues.[4]

This filming technique, which conveys the impression of continuous action, also serves to lengthen the duration of the action in the mind of the viewer. In a 2002 article in Scientific American, Antonio Damasio argues that the time frame covered by the movie, which lasts 80 minutes and is supposed to be in "real time", is actually longer—a little more than 100 minutes. This, he states, is accomplished by speeding up the action: the formal dinner lasts only 20 minutes, the sun sets too quickly and so on.[12][13]

Actor James Stewart found the whole process highly exasperating, saying: "The really important thing being rehearsed here is the camera, not the actors!" Much later, Stewart said of the film: "It was worth trying—nobody but Hitch would have tried it. But it really didn't work."[14]

The cyclorama in the background was the largest backing ever used on a sound stage.[4] It included models of the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. Numerous chimneys smoke, lights come on in buildings, neon signs light up and the sunset slowly unfolds as the movie progresses. Within the course of the film, the clouds—made of spun glass—change position and shape eight times.[4]

Homosexual subtext

[edit]Recent reviews and criticism of Rope have noticed a homosexual subtext between the characters Brandon and Phillip,[15][16][17] even though homosexuality was a highly controversial theme for the 1940s. The play on which the film was based explicitly portrays Brandon and Phillip as being in a homosexual relationship.[18] John Dall, who played Brandon, is believed to have been gay,[19][20] as was screenwriter Arthur Laurents, while co-star Farley Granger was bisexual.[21]

Interviewed by Vito Russo for Russo's 1981 book The Celluloid Closet, Laurents stated: "We never discussed, Hitch and I, whether the characters in Rope were homosexuals, but I thought it was apparent."[22] In the 1995 documentary film adaptation of Russo's book, Laurents says: "I don't think the censors at that time realized this was about gay people. They didn't have a clue what was and what wasn't, that's how it got by."[23] In the same documentary, Granger says of Brandon and Phillip: "We knew that they were gay, yeah, sure. I mean, nobody said anything about it—this was 1947, let's not forget that! But that was one of the points of the film, in a way."[23]

Long takes

[edit]Hitchcock shot long unbroken takes lasting up to ten minutes (the length of a film camera magazine), involving carefully choreographed camera and actor movement, though most shots in the film wound up being shorter.[24] Every other segment ends by panning against or tracking into an object—a man's jacket blocking the entire screen, or the back of a piece of furniture, for example. In this way, Hitchcock effectively masked half the cuts in the film.[25]

However, at the end of 20 minutes (two magazines of film make one reel of film on the projector in the movie theater), the projectionist—when the film was shown in theaters—had to change reels. On these changeovers, Hitchcock cuts to a new camera setup, deliberately not disguising the cut. A description of the beginning and end of each segment follows.

| Segment | Length | Time-code | Start | Finish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 09:34 | 00:02:30 | Close-up (CU), strangulation | Blackout on Brandon's back |

| 2 | 07:51 | 00:11:59 | Black, pan off Brandon's back | CU Kenneth: "What do you mean?" |

| 3 | 07:18 | 00:19:45 | Unmasked cut, men crossing to Janet | Blackout on Kenneth's back |

| 4 | 07:08 | 00:27:15 | Black, pan off Kenneth's back | CU Phillip: "That's a lie." |

| 5 | 09:57 | 00:34:34 | Unmasked cut, CU Rupert | Blackout on Brandon's back |

| 6 | 07:33 | 00:44:21 | Black, pan off Brandon's back | Mrs. Wilson (OS): "Excuse me, sir." |

| 7 | 07:46 | 00:51:56 | Unmasked cut, Mrs. Wilson: "There's a lady phoning..." | Blackout on Brandon |

| 8 | 10:06 | 00:59:44 | Black, pan off Brandon | CU Brandon's hand in gun pocket |

| 9 | 04:37 | 01:09:51 | Unmasked cut, CU Rupert | Blackout on lid of chest |

| 10 | 05:38 | 01:14:35 | Black, tilt up from lid of chest | End of film |

Hitchcock told François Truffaut in the book-length Hitchcock/Truffaut (Simon & Schuster, 1967) that he ended up re-shooting the last four or five segments because he was dissatisfied with the color of the sunset.

Hitchcock used this long-take approach again to a lesser extent on his next film, Under Capricorn (1949), and in a very limited way in his film Stage Fright (1950).

Director's cameo

[edit]

Alfred Hitchcock's cameo appearance is a signature occurrence in most of his films. At 55:19 into the film, a red neon sign in the far background showing Hitchcock's trademark profile starts blinking. As the guests are escorted to the door, actors Joan Chandler and Douglas Dick stop to have a few words and the sign flashes in the background several times.

There is some debate as to whether Hitchcock makes another cameo earlier in the film. In the making-of documentary, Rope Unleashed, Arthur Laurents says that Hitchcock can be seen walking down the Manhattan street immediately after the title sequence.[26] The individual significantly resembles Hitchcock, yet some believe that it is a myth. In The Encyclopedia of Alfred Hitchcock, Thomas M. Leitch claims that the production records in the Warner Bros. archive show that the neon sign is Hitchcock's only appearance in the entire film.[full citation needed]

Production credits

[edit]The production credits on the film were as follows:

- Director – Alfred Hitchcock

- Writing – Arthur Laurents (screenplay), Hume Cronyn (adaptation)

- Cinematography – Joseph Valentine and William V. Skall (directors of photography)

- Art direction – Perry Ferguson (art director), Emile Kuri and Howard Bristol (set decorators)

- Technicolor color director – Natalie Kalmus

- Production manager – Fred Ahern

- Film editor – William H. Ziegler

- Assistant director – Lowell J. Farrell

- Makeup artist – Perc Westmore

- Operators of camera movement – Edward Fitzgerald, Paul G. Hill, Richard Emmons, Morris Rosen

- Sound – Al Riggs

- Lighting technician – Jim Potevin

- Music – Leo F. Forbstein (musical director), The Three Suns (radio sequence)

- Costumes – Adrian (Miss Chandler's dress)

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]According to Warner Bros. records, the film earned $2,028,000 domestically and $720,000 overseas.[3]

Critical response

[edit]Contemporary reviews were mixed. Variety wrote:

Hitchcock could have chosen a more entertaining subject with which to use the arresting camera and staging technique displayed in Rope ... The continuous action and the extremely mobile camera are technical features of which industry craftsmen will make much, but to the layman audience effect is of a distracting interest.[27]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote:

The novelty of the picture is not in the drama itself, it being a plainly deliberate and rather thin exercise in suspense, but merely in the method which Mr. Hitchcock has used to stretch the intended tension for the length of the little stunt. And, with due regard for his daring (and for that of Transatlantic Films), one must bluntly observe that the method is neither effective nor does it appear that it could be.[28]

The Chicago Tribune's Mae Tinee was candid about her reactions:

If Mr. Hitchcock's purpose in producing this macabre tale of murder was to shock and horrify, he has succeeded all too well. The opening scene is sickeningly graphic, establishing a feeling of revulsion which seldom left me during the entire film....Undeniably clever in all of its aspects, this film is a gruesome affair and—to me, at least—was a gruelling spectacle, not recommended to the sensitive.[29]

John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote:

In addition to the fact that it has little or no movement, Rope is handicapped by some of the most relentlessly arch dialogue you ever heard.[30]

The Monthly Film Bulletin found that the actors, "for the most part, are excellent", but that, "as a film, much of the suspense of the story and the drama of the original written material has been lost because the continual movement within a confined space, although more fluid, is slower and more tiring to watch than a film which has been edited by the conventional method."[31]

Harrison's Reports gave the film a very positive review, calling it "an exceptionally fine psychological thriller" with "excellent" acting and "an ingenious technique, and under Hitchcock's superb handling it serves to heighten the atmosphere of mounting suspense and suspicion".[32]

Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times wrote:

It is unusual enough to shine more as a technical tour de force than as a moving sort of film ... The interesting experimental values in this Hitchcock production could never be denied, yet I would not rate it one of his best.[33]

In Time's 1948 review, the play that the film was based on is called an "intelligent and hideously exciting melodrama" though "in turning it into a movie for mass distribution, much of the edge [is] blunted" explaining:

Much of the play's deadly excitement dwelt in [the] juxtaposition of callow brilliance and lavender dandyism with moral idiocy and brutal horror. Much of its intensity came from the shocking change in the teacher, once he learned what was going on. In the movie, the boys and their teacher are shrewdly plausible but much more conventional types. Even so, the basic idea is so good and, in its diluted way, Rope is so well done that it makes a rattling good melodrama.[34]

On its theatrical release in 1948, Rope performed poorly at the box office. In Rope Unleashed, screenwriter Arthur Laurents attributed this failure to audience uneasiness with the homosexual undertones in the relationship between the two lead characters.[26]

Nearly 36 years later, Vincent Canby, also of The New York Times, called the "seldom seen" and "underrated" film "full of the kind of self-conscious epigrams and breezy ripostes that once defined wit and decadence in the Broadway theater"; it is a film "less concerned with the characters and their moral dilemmas than with how they look, sound and move, and with the overall spectacle of how a perfect crime goes wrong".[15]

Roger Ebert wrote in 1984: "Alfred Hitchcock called Rope an 'experiment that didn't work out', and he was happy to see it kept out of release for most of three decades", but went on to say that "Rope remains one of the most interesting experiments ever attempted by a major director working with big box-office names, and it's worth seeing ...."[11]

A BBC review of the DVD release, in 2001, called the film "technically and socially bold" and pointed out that given "how primitive the Technicolor process was back then", the DVD's image quality is "by those standards quite astonishing"; the release's "2.0 mono mix" was clear and reasonably strong, though "distortion creeps into the music".[35]

Rope holds a score of 93% on the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes based on 54 reviews, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "As formally audacious as it is narratively brilliant, Rope connects a powerful ensemble in service of a darkly satisfying crime thriller from a master of the genre".[36] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average, reports a score of 73 out of 100 based on reviews from ten critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[37]

See also

[edit]- Compulsion, a 1959 film based on the Leopold and Loeb events.

- R.S.V.P., a 2002 film that borrowed several key elements from Rope, and in which the film is discussed.

- Swoon, an independent 1992 film by Tom Kalin, depicting the actual Leopold and Loeb events.

Notes

[edit]- ^ After the film's release, Warner Bros. sold the film to Associated Artists Productions in 1956, and then the film's rights transferred to Hitchcock's estate, where they were acquired by Universal Pictures in 1983.[1][2]

References

[edit]- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (2003). Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Wiley. p. 653.

- ^ Rossen, Jake (February 5, 2016). "When Hitchcock Banned Audiences From Seeing His Movies". Mental Floss. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Appendix 1: Warner Bros financial information in The William Schaefer Ledger". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 15 (sup1): 1–31. 1995. doi:10.1080/01439689508604551. — p. 29

- ^ a b c d Truffaut, François (1967). Hitchcock/Truffaut. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ "109-Million Techni Sked". Variety. Vol. 169, no. 11. February 18, 1948. p. 14.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1948". Variety. Vol. 173, no. 4. January 5, 1949. p. 46.

- ^ Rope Unleashed – Making Of (2000) – documentary on the Universal Studios DVD of the film.

- ^ Crow, David (August 29, 2016). "Before Birdman There Was Alfred Hitchcock's Rope". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Bordwell, David (2008). Poetics of cinema. New York: Routledge. pp. 32–36. ISBN 9780415977791.

- ^ "Lifeboat". Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (June 15, 1984). "Rope". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Damasio, Antonio. "Remembering When" in Scientific American, 2002.

- ^ Damasio, Antonio (January 2012). "How Hitchcock's Rope Stretches Time". Scientific American. 23 (4s): 46–47. doi:10.1038/scientificamericantime1114-46.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (March 1983). The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. Little Brown & Co. p. 306. ISBN 0-316-80723-0.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (June 3, 1984). "Hitchcock's 'Rope:' A Stunt to Behold". The New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Miller, D. A. (1991). "Anal Rope". Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories. Routledge. pp. 119–141. ISBN 0-415-90237-1.

- ^ "When Hitchcock Went Gay: 'Strangers On A Train' And 'Rope'". August 11, 2014.

- ^ Badman, Scott; Hosier, Connie Russell (February 7, 2017). "Gay Coding in Hitchcock Films". American Mensa.

- ^ Burroughs Hannsberry, Karen (2003). Bad Boys: the Actors of Film Noir. McFarland. p. 176. ISBN 0786414847.

- ^ Mann, William J. (2001). Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood. Viking. p. 263. ISBN 0670030171.

- ^ Granger, Farley, Include Me Out. New York: St. Martin's Press 2007. ISBN 0-312-35773-7, pp. 37-41

- ^ Russo, Vito (1987). "The Way We Weren't: The Invisible Years". The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (Revised ed.). Harper & Row. p. 94. ISBN 0-06-096132-5.

- ^ a b Epstein, Rob and Friedman, Jeffrey (Directors) (1995). The Celluloid Closet (Documentary). Sony Pictures Classics.

- ^ Jacobs, Steven (2007). The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. p. 272.

- ^ Connolly, Mike (March 10, 1948). "Revolutionary No-Pause Filming On 'Rope' Stress New Pic Technique". Variety. Vol. 170, no. 1. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Interview with Arthur Laurents in the making-of documentary, Rope Unleashed.

- ^ "Rope". Variety. Vol. 171, no. 13. September 1, 1948. p. 14.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 17, 1948). "'Rope': An Exercise in Suspense Directed by Alfred Hitchcock". The New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Tinee, Mae (October 1, 1948). "Movie, 'Rope,' Cleverly Done but Gruesome." Chicago Tribune.

- ^ McCarten, John (September 4, 1948). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 61.

- ^ "Rope (1948)". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 15 (180): 176. December 1948.

- ^ "'Rope' with James Stewart, John Dall and Farley Granger". Harrison's Reports. August 28, 1948. p. 138.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (September 25, 1948). "'Rope' Attains Ultimate Grimness in Murder Vein". Los Angeles Times. p. 11.

- ^ "The New Pictures". Time. September 13, 1948. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Haflidason, Almar (June 18, 2001). "Rope DVD (1948)". BBC. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ "Rope (1948)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "Rope Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Neimi, Robert (2006). History in the Media: Film and Television. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-952-X. OCLC 85688866.

Further reading

[edit]- Connelly, Thomas J. (2019). "Big Window, Big Other: Enjoyment and Spectatorship in Alfred Hitchcock's Rope". Cinema of Confinement (PDF). Chicago: Northwestern UP. pp. 29–42. doi:10.25969/mediarep/12913. ISBN 978-0-8101-3923-7..

- Miller, D. A. (Fall 1990). "Anal Rope". Representations. 32 (32). University of California Press: 114–133. doi:10.2307/2928797. JSTOR 2928797.

- Wollen, Peter (1999). "Rope: Three Hypotheses". In Richard Allen; S. Ishii-Gonzalès (eds.). Alfred Hitchcock: Centenary Essays. London: BFI Pub. ISBN 9780851707358. OCLC 44454904.

External links

[edit]- Rope at IMDb

- Rope at the TCM Movie Database

- Rope at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Trailer for Rope

- 1948 films

- 1948 crime drama films

- 1940s crime thriller films

- 1940s LGBTQ-related films

- 1940s psychological thriller films

- American crime drama films

- American crime thriller films

- American films based on plays

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American psychological thriller films

- 1940s English-language films

- Films à clef

- Films about educators

- Films about murder

- Films based on the Leopold and Loeb murder

- Films directed by Alfred Hitchcock

- Films produced by Alfred Hitchcock

- Films set in apartment buildings

- Films set in Manhattan

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- Films with screenplays by Hume Cronyn

- LGBTQ-related crime drama films

- LGBTQ-related crime thriller films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films with screenplays by Arthur Laurents

- 1940s American films

- English-language crime drama films

- English-language crime thriller films