Horned God

| Horned God | |

|---|---|

God of nature, wilderness, sexuality, hunting | |

| |

| Consort | Triple Goddess |

| Part of a series on |

| Wicca |

|---|

|

The Horned God is one of the two primary deities found in Wicca and some related forms of Neopaganism. The term Horned God itself predates Wicca, and is an early 20th-century syncretic term for a horned or antlered anthropomorphic god partly based on historical horned deities.[1]

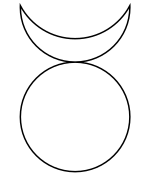

The Horned God represents the male part of the religion's duotheistic theological system, the consort of the female Triple goddess of the Moon or other Mother goddess.[2] In common Wiccan belief, he is associated with nature, wilderness, sexuality, hunting, and the life cycle.[3]: 32–34 Whilst depictions of the deity vary, he is always shown with either horns or antlers upon his head, often depicted as being theriocephalic (having a beast's head), in this way emphasizing "the union of the divine and the animal", the latter of which includes humanity.[4]: 11

In traditional Wicca (British Traditional Wicca), he is generally regarded as a dualistic god of twofold aspects: bright and dark, night and day, summer and winter, the Oak King and the Holly King. In this dualistic view, his two horns symbolize, in part, his dual nature. (The use of horns to symbolize duality is also reflected in the phrase "on the horns of a dilemma.") The three aspects of the Goddess and the two aspects of the Horned god are sometimes mapped on to the five points of the Pentagram or Pentacle, although which points correspond to which deity aspects varies. In some other systems, he is represented as a triune god, split into three aspects that reflect those of the Triple goddess: the Youth (Warrior), the Father, and the Sage.

The Horned God has been explored within several psychological theories and has become a recurrent theme in fantasy literature.[5]: 872

In Wicca

[edit]

In traditional and mainstream Wicca, the Horned God is viewed as the divine male principality, being both equal and opposite to the Goddess. The Wiccan god himself can be represented in many forms, including as the Sun God, the Sacrificed God and the Vegetation God,[3] although the Horned God is the most popular representation. The pioneers of the various Wiccan or Witchcraft traditions, such as Gerald Gardner, Doreen Valiente and Robert Cochrane, all claimed that their religion was a continuation of the pagan religion of the Witch-Cult following historians who had purported the Witch-Cult's existence, such as Jules Michelet and Margaret Murray.

For Wiccans, the Horned God is "the personification of the life force energy in animals and the wild"[6] and is associated with the wilderness, virility and the hunt.[7]: 16 Doreen Valiente writes that the Horned God also carries the souls of the dead to the underworld.[8]

Wiccans generally, as well as some other neopagans, tend to conceive of the universe as polarized into gender opposites of male and female energies. In traditional Wicca, the Horned God and the Goddess are seen as equal and opposite in gender polarity. However, in some of the newer traditions of Wicca, and especially those influenced by feminist ideology, there is more emphasis on the Goddess, and consequently the symbolism of the Horned God is less developed than that of the Goddess.[9]: 154 In Wicca the cycle of the seasons is celebrated during eight sabbats called The Wheel of the Year. The seasonal cycle is imagined to follow the relationship between the Horned God and the Goddess.[7] The Horned God is born in winter, impregnates the Goddess and then dies during the autumn and winter months and is then reborn by the Goddess at Yule.[10] The different relationships throughout the year are sometimes distinguished by splitting the god into aspects, the Oak King and the Holly King.[7] The relationships between the Goddess and the Horned God are mirrored by Wiccans in seasonal rituals. There is some variation between Wiccan groups as to which sabbat corresponds to which part of the cycle. Some Wiccans regard the Horned God as dying at Lammas, August 1; also known as Lughnasadh, which is the first harvest sabbat. Others may see him dying at Mabon, the autumn equinox, or the second harvest festival. Still other Wiccans conceive of the Horned God dying on October 31, which Wiccans call Samhain, the ritual of which is focused on death. He is then reborn on Winter Solstice, December 21.[11]: 190

Other important dates for the Horned God include Imbolc when, according to Valiente, he leads a wild hunt.[8]: 191 In Gardnerian Wicca, the Dryghten prayer recited at the end of every ritual meeting contains the lines referring to the Horned God:

In the name of the Lady of the Moon,

and the Horned Lord of Death and Resurrection[12]

According to Sabina Magliocco,[12]: 28 Gerald Gardner says (in 1959's The Meaning of Witchcraft) that The Horned God is an Under-god, a mediator between an unknowable supreme deity and the people. (In Wiccan liturgy in the Book of Shadows, this conception of an unknowable supreme deity is referred to as "Dryghtyn." It is not a personal god, but rather an impersonal divinity similar to the Tao of Taoism.)

Whilst the Horned God is the most common depiction of masculine divinity in Wicca, he is not the only representation. Other examples include the Green Man and the Sun God.[3] In traditional Wicca, however, these other representations of the Wiccan god are subsumed or amalgamated into the Horned God, as aspects or expressions of him. Sometimes this is shown by adding horns or antlers to the iconography. The Green Man, for example, may be shown with branches resembling antlers; and the Sun God may be depicted with a crown or halo of solar rays, that may resemble horns. These other conceptions of the Wiccan god should not be regarded as displacing the Horned God, but rather as elaborating on various facets of his nature. Doreen Valiente has called the Horned God "the eldest of gods" in both The Witches Creed and also in her Invocation To The Horned God.

Wiccans believe that The Horned God, as Lord of Death, is their "comforter and consoler" after death and before reincarnation; and that he rules the Underworld or Summerland where the souls of the dead reside as they await rebirth. Some, such as Joanne Pearson, believe that this is based on the Mesopotamian myth of Inanna's descent into the underworld, though this has not been confirmed.[13]: 147

Names

[edit]

Doreen Valiente, a former High Priestess of the Gardnerian tradition, claimed that Gerald Gardner's Bricket Wood coven referred to the god as Cernunnos, or Kernunno, which is a Latin word, discovered on a stone carving found in France, meaning "the Horned One". Valiente claimed that the coven also referred to the god as Janicot,[needs IPA] which she theorised was of Basque origin, and Gardner also used this name in his novel High Magic's Aid.[14]: 52–53

Stewart Farrar, a High Priest of the Alexandrian tradition referred to the Horned God as Karnayna, which he believed was a corruption of Cernunnos.[15] The historian Ronald Hutton suggests the term derived instead from the Arabic Dhul-Qarnayn meaning "Horned One", as Murray offered in her 1931 book The God of the Witches, a source that likely influenced Alex Sanders.[16]: 331 Prudence Jones has suggested that the name may instead derive from Karneios, a Spartan deity conflated with Apollo as a subordinate consort to Diana.[17]

In the writings of Charles Cardell and Raymond Howard, the god was referred to as Atho. Howard had a wooden statue of Atho's head which he claimed was 2200 years old, but the statue was stolen in April 1967. Howard's son later admitted that his father had carved the statue himself.[18]

In Cochrane's Craft, which was founded by Robert Cochrane, the Horned God was often referred to by a Biblical name; Tubal-cain, who, according to the Bible was the first blacksmith.[19] In this neopagan concept, the god is also referred to as Brân, a Welsh mythological figure, Wayland, the smith in Germanic mythology, and Herne, a horned figure from English folklore.[19]

In the neopagan tradition of Stregheria, founded by Raven Grimassi and loosely inspired by the works of Charles Godfrey Leland, the Horned God goes by several names, including Dianus, Faunus, Cern, and Actaeon.[20]

In the Hinduism, the Horned God is referred to Pashupati, See Pashupati seal.[21]

In psychology

[edit]Jungian analysis

[edit]

Sherry Salman considers the image of the Horned God in Jungian terms, as an archetypal protector and mediator of the outside world to the objective psyche. In her theory the male psyche's 'Horned God' frequently compensates for inadequate fathering.

When first encountered, the figure is a dangerous, 'hairy chthonic wildman' possessed of kindness and intelligence. If repressed, later in life The Horned God appears as the lord of the Otherworld, or Hades. If split off entirely, he leads to violence, substance abuse and sexual perversion. When integrated he gives the male an ego "in possession of its own destructiveness" and for the female psyche gives an effective animus relating to both the physical body and the psyche.[22]

In considering the Horned God as a symbol recurring in women's literature, Richard Sugg suggests the Horned God represents the 'natural Eros', a masculine lover subjugating the social-conformist nature of the female shadow, thus encompassing a combination of the shadow and animus. One such example is Heathcliff from Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights. Sugg goes on to note that female characters who are paired with this character usually end up socially ostracised, or worse—in an inverted ending to the male hero-story.[23]: 162

Humanistic psychology

[edit]Following the work of Robert Bly in the Mythopoetic men's movement, John Rowan proposes the Horned God as a "Wild Man" be used as a fantasy image or "sub-personality"[24]: 38 helpful to men in humanistic psychology, and escaping from "narrow societal images of masculinity"[25]: 249 encompassing excessive deference to women and paraphillia.[25]: 57–57

Theories of historical origins

[edit]

Many horned deities are known to have been worshipped in various cultures throughout history. Evidence for horned gods appear very early in the human record. The so-called Sorcerer dates from perhaps 13,000 BCE. Twenty-one red deer headdresses, made from the skulls of the red deer and likely fitted with leather laces, have been uncovered at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr. They are thought to date from roughly 9,000 BCE.[26] Several theories have been created to establish historical roots for modern Neopagan worship of a Horned God.

Margaret Murray

[edit]Following the writings of suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage[27] and others, Margaret Murray, in her 1921 book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, proposed the theory that the witches of the early-modern period were remnants of a pagan cult and that the Christian Church had declared the god of the witches was in fact the Devil. Without recourse to any specific representation of this deity, Murray speculates that the head coverings common in inquisition-derived descriptions of the devil "may throw light on one of the possible origins of the cult."[28]

In 1931 Murray published a sequel, The God of the Witches, which tries to gather evidence in support of her witch-cult theory. In Chapter 1 "The Horned God".[29] Murray claims that various depictions of humans with horns from European and Indian sources, ranging from the paleolithic French cave painting of "The Sorcerer" to the Indic Pashupati to the modern English Dorset Ooser, are evidence for an unbroken, Europe-wide tradition of worship of a singular Horned God. Murray derived this model of a horned god cult from James Frazer and Jules Michelet.[30]: 36

In dealing with "The Sorcerer",[28]: 23–4 the earliest evidence claimed, Murray based her observations on a drawing by Henri Breuil, which some modern scholars such as Ronald Hutton claim is inaccurate. Hutton states that modern photographs show the original cave art lacks horns, a human torso or any other significant detail on its upper half.[31]: 34 However, others, such as celebrated prehistorian Jean Clottes, assert that Breuil's sketch is indeed accurate. Clottes stated that "I have seen it myself perhaps 20 times over the years".[32]

Breuil considered his drawing to represent a shaman or magician—an interpretation which gives the image its name. Murray having seen the drawing called Breuil's image "the first depiction of a deity", an idea which Breuil and others later adopted.

Murray also used an inaccurate drawing of a mesolithic rock-painting at Cogul in northeast Spain as evidence of group religious ceremony of the cult, although the central male figure is not horned.[28]: 65 The illustration she used of the Cogul painting leaves out a number of figures, human and animal, and the original is more likely a sequence of superimposed but unrelated illustrations, rather than a depiction of a single scene.[16]: 197

Despite widespread criticism of Murray's scholarship some minor aspects of her work continued to have supporters.[33]: 9 [34]

Influences from literature

[edit]The popular image of the Greek god Pan was removed from its classical context in the writings of the Romantics of the 18th century and connected with their ideals of a pastoral England. This, along with the general public's increasing lack of familiarity of Greek mythology at the time led to the figure of Pan becoming generalised as a 'horned god', and applying connotations to the character, such as benevolence that were not evident in the original Greek myths which in turn gave rise to the popular acceptance of Murray's hypothetical horned god of the witches.[16]

The reception of Aradia amongst Neopagans has not been entirely positive. Clifton suggests that modern claims of revealing an Italian pagan witchcraft tradition, for example those of Leo Martello and Raven Grimassi, must be "match[ed] against", and compared with the claims in Aradia. He further suggests that a lack of comfort with Aradia may be due to an "insecurity" within Neopaganism about the movement's claim to authenticity as a religious revival.[35]: 61

Valiente offers another explanation for the negative reaction of some neopagans; that the identification of Lucifer as the god of the witches in Aradia was "too strong meat" for Wiccans who were used to the gentler, romantic paganism of Gerald Gardner and were especially quick to reject any relationship between witchcraft and Satanism.[36]

In 1985 Classical historian Georg Luck, in his Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, theorised that the origins of the Witch-cult may have appeared in late antiquity as a faith primarily designed to worship the Horned God, stemming from the merging of Cernunnos, a horned god of the Celts, with the Greco-Roman Pan/Faunus,[37] a combination of gods which he posits created a new deity, around which the remaining pagans, those refusing to convert to Christianity, rallied and that this deity provided the prototype for later Christian conceptions of the Devil, and his worshippers were cast by the Church as witches.[37]

Influences from occultism

[edit]

Eliphas Levi's image of "Baphomet" serves as an example of the transformation of the Devil into a benevolent fertility deity and provided the prototype for Murray's horned god.[38] Murray's central thesis that images of the Devil were actually of deities and that Christianity had demonised these worshippers as following Satan, is first recorded in the work of Levi in the fashionable 19th-century Occultist circles of England and France.[38] Levi created his image of Baphomet, published in his Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (1855), by combining symbolism from diverse traditions, including the Diable card of the 16th and 17th century Tarot of Marseille. Lévi called his image "The Goat of Mendes", possibly following Herodotus' account[39] that the god of Mendes—the Greek name for Djedet, Egypt—was depicted with a goat's face and legs. Herodotus relates how all male goats were held in great reverence by the Mendesians, and how in his time a woman publicly copulated with a goat.[40] E. A. Wallis Budge writes,

At several places in the Delta, e.g. Hermopolis, Lycopolis, and Mendes, the god Pan and a goat were worshipped; Strabo, quoting (xvii. 1, 19) Pindar, says that in these places goats had intercourse with women, and Herodotus (ii. 46) instances a case which was said to have taken place in the open day. The Mendisians, according to this last writer, paid reverence to all goats, and more to the males than to the females, and particularly to one he-goat, on the death of which public mourning is observed throughout the whole Mendesian district; they call both Pan and the goat Mendes, and both were worshipped as gods of generation and fecundity. Diodorus (i. 88) compares the cult of the goat of Mendes with that of Priapus, and groups the god with the Pans and the Satyrs. The goat referred to by all these writers is the famous Mendean Ram, or Ram of Mendes, the cult of which was, according to Manetho, established by Kakau, the king of the IInd dynasty.[41]

Historically, the deity that was venerated at Egyptian Mendes was a ram deity Banebdjedet (literally Ba of the lord of djed, and titled "the Lord of Mendes"), who was the soul of Osiris. Lévi combined the images of the Tarot of Marseilles Devil card and refigured the ram Banebdjed as a he-goat, further imagined by him as "copulator in Anep and inseminator in the district of Mendes".

Gerald Gardner and Wicca

[edit]

Margaret Murray's theory of the historical origins of the Horned God has been used by Wiccans to create a myth of historical origins for their religion.[7]: 110 There is no verifiable evidence to support claims that the religion originates earlier than the mid-20th century.[16]

Modern scholarship has disproved Margaret Murray's theory. However, various horned gods and mother goddesses were indeed worshipped in the British Isles during the ancient and early Medieval periods.[42]

The "father of Wicca", Gerald Gardner, who adopted Margaret Murray's thesis, claimed Wicca was a modern survival of an ancient pan-European pagan religion.[43] Gardner states that he had reconstructed elements of the religion from fragments, incorporating elements from Freemasonry, the Occult, and Theosophy, which came together in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where Gardner met Aleister Crowley.[44]: 27

Gerald Gardner was initiated into the O.T.O. by Aleister Crowley and subsequently went on to found the Neopagan religion of Wicca. Various scholars on early Wiccan history, such as Ronald Hutton, Philip Heselton, and Leo Ruickbie concur that witchcraft's early rituals, as devised by Gardner, contained much from Crowley's writings such as the Gnostic Mass.

Romano-Celtic fusion

[edit]Georg Luck, repeats part of Murray's theory, stating that the Horned God may have appeared in late antiquity, stemming from the merging of Cernunnos, an antlered god of the Continental Celts, with the Greco-Roman Pan/Faunus,[37] a combination of gods which he posits created a new deity, around which the remaining pagans, those refusing to convert to Christianity, rallied and that this deity provided the prototype for later Christian conceptions of the devil, and his worshippers were cast by the Church as witches.[37]

Art, fantasy and science fiction

[edit]

In 1908's The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, in Chapter 7, "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn", Ratty and Mole meet a mystical horned being, powerful, fearsome and kind.[35]: 85 Grahame's work was a significant part of the cultural milieu which stripped the Greek god Pan of his cultural identity in favor of an unnamed, generic horned deity which led to Murray's thesis of historical origins.

Outside of works that predate the publication of Murray's thesis, horned god motifs and characters appear in fantasy literature that draws upon her work and that of her followers.

The 1947 short story "Cwm Garon" by L. T. C. Rolt (published in Rolt's collection Sleep No More) describes a traveller encountering a remote Welsh village, where the inhabitants worship a demonic entity that appears as a horned god.[45]: 275

In the novel Childhood's End (1953) by Arthur C. Clarke, all humans have a collective premonition, also described as a memory of the future, of horned aliens which arrive to usher in a new phase of human evolution. The collective subconscious image of the horned aliens is what accounts for mankind's image of the devil or Satan. This theme is also explored in the Doctor Who story The Dæmons in 1971, where the local superstitions around a landmark known as The Devil's Hump prove to be based on reality, as aliens from the planet Dæmos have been affecting man's progress over the millennia and the Hump actually contains a spacecraft. The only Dæmon to appear is a classic interpretation of a horned satyr-like being with hooves.

In the 1950s TV series created by Nigel Kneale, Quatermass and the Pit, depictions of supernatural horned entities, with specific reference to prehistoric cave-art and shamanistic horned head-dress are revealed to be a "race-memory" of psychic Martian grasshoppers, manifested at the climax of the film by a fiery horned god.[46]: 244

The 1956 novel The Golden Strangers by Henry Treece features a "Hornman", a priest of the "Children of the Sun" tribe. The Hornman performs numerous human sacrifices while wearing a hood with stag's horns attached to it. According to historian Marion Gibson, Treece based the Hornman character on Murray's conception of the Horned God.[47]: 144

The Philip José Farmer novel Flesh depicts a future society where the protagonist, Peter Stagg, adopts the role of the "Horned King". The Horned King serves as a figure of male fertility to a goddess-worshipping female priesthood, and resembles Murray's conception of the Horned God.[48] : 143

In some of Rosemary Sutcliff's novels, including the medieval-set novel Knight's Fee (1960) and the Arthurian novel Sword at Sunset (1963), several of the heroes worship a stag-antlered deity called the Horned One. The depiction of this deity is similar to that given in Murray's writings.[49]: 48 [50]: 203

Murray's theories have been seen to have had influence on the horror film The Blood on Satan's Claw (1971), where a murderous female-led cult worships a horned deity named Behemoth.[51]: 94

In the fantasy novel Too Long A Sacrifice by Mildred Downey Broxon (1981), a male character, Tadhg, is an avatar of a benevolent Horned God.[52]: 26

Marion Zimmer Bradley, who acknowledges the influence of Murray, uses the figure of the "horned god" in her feminist fantasy transformation of Arthurian myth, Mists of Avalon (1984), and portrays ritualistic incest between King Arthur as the representative of the horned god and his sister Morgaine as the "spring maiden".[53]: 106

In the Richard Carpenter television series Robin of Sherwood (1984), Robin Hood is taught and guided by a shaman-like figure called Herne the Hunter (a figure from English legend). Herne wears a headdress of a horned stag's head. Carpenter stated in an interview that Herne was based on the Pagan idea of the Horned God.[54]: 33

In June 1986, the comic book 2000 AD published the first part of a serial story called Sláine and the Horned God, written by Pat Mills and illustrated by Simon Bisley. Based in Celtic mythology, the Horned God is identified with Cernunnos and is the primary antagonist in a story rich with antagonists. He presents as a Fertility God who has largely lost his mind and become nihilistic.[55] : 282

The titular smith of the Fay Sampson novel Black Smith's Telling (1990) is depicted as the leader of an benevolent "Old Religion" that worships a Horned God. [56]: 505

The 1992 Discworld novel Lords and Ladies, by Terry Pratchett, features a King of the Elves who is strongly reminiscent of the Horned God. Although not worshipped by the witches who are the heroines of the book (indeed, quite the reverse), they temporarily ally themselves with him out of necessity.

The 1995 fantasy novel The Wild Hunt by Jane Yolen features a supernatural being named the Horned King, who resembles the Horned God, as the novel's antagonist.[57]: 51

In the popular video game Morrowind, its expansion Bloodmoon (2003) has a plot enemy known as Hircine, the Daedric god of the Hunt, who appears as a horned man with the face of a deer skull. He condemned his "hounds" (werewolves) to walk the mortal ground during the Bloodmoon until a champion defeats him or Bloodmoon falls. When in combat, Hircine appears as a horned wolf or bear.

The historical novel The White Mare (2004) by Jules Watson, set in Scotland in the year 79 CE, features a scene where the heroine is partnered with a priest of the Horned God during a religious ceremony.[47]: 163

The historical novel Outlaw (2009) by Angus Donald, has Robin Hood take part in a violent pagan ceremony where Robin plays the part of Cernunnos, here named as the Horned God.[58] : 76

Tim Powers' novella Salvage and Demolition (2013) involves a quest for a manuscript written by a being called Aker, who is also designated as the Horned God.[59] : 120

The 2015 film The Witch, which takes place in 17th century New England during the latter end of the early modern inquisition against witchcraft that swept across Europe, deals with an interpretation of the Horned God, which takes the form of Black Phillip, the family goat.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Michael D. Bailey Witchcraft Historiography (review) in Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft – Volume 3, Number 1, Summer 2008, pp. 81–85

- ^ "from the library of the Order of Bards, Ovates & Druids". Druidry.org. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- ^ a b c Farrar, Janet; Farrar, Stewart (1989). The Witches' god: Lord of the Dance. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-3319-2.

- ^ d'Este, Sorita (2008). Horns of Power. London: Avalonia. ISBN 978-1-905297-17-7.

- ^ Clute, John The Encyclopedia of Fantasy Clute, John; Grant, John (1997). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Orbit. ISBN 1-85723-368-9.

- ^ Starhawk (2006). "Some basic definitions". On-faith. News-Week. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d Davy, Barbara Jane (2006). Introduction to Pagan Studies. AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7591-0819-6.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Susan (2005). The nature of magic. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-84520-095-0.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1997). New Age Religion and Western Culture. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-3854-6.

- ^ Farrer, Janet; Stewart Farrer (2002). The Witches' bible. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0-7090-7227-9.

- ^ Salomonsen, Jone (2001). Enchanted Feminism. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22393-8.

- ^ a b Magliocco, Sabina (2004). Witching Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3803-6.

- ^ Pearson, Joanne (2002). A Popular Dictionary of Paganism. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1591-6.

- ^ Valiente, Doreen (2007). The Rebirth of Witchcraft. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7090-8369-6.

- ^ Farrar, Stewart (2010). What Witches Do. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7090-9014-4.

- ^ a b c d Hutton, Ronald (1995). The Triumph of the Moon: a History of Modern Pagan Witchcaraft. Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 0-19-285449-6.

- ^ Jones, P. 2005. A Goddess Arrives: Nineteenth Century Sources of the New Age Triple Moon Goddess. Culture and Cosmos, 19(1): 45–70.

- ^ Seims, Melissa (2007). "The Coven of Atho". Thewica.co.uk.

- ^ a b Howard, Mike (2001). The Roebuck in the Thicket: An Anthology of the Robert Cochrane Witchcraft Tradition. Capall Bann Publishing. ISBN 1-86163-155-3. Chapter One.

- ^ WiseWitch (5 August 2020) [24 October 2017]. "Wicca- Wiccan Symbols the Ultimate Guide".

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2022). "The Hindu- Pashupati and the Harappan seal". The Hindu.

- ^ Kalsched, Donald (1996). The Inner World of Trauma. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12329-1.

- ^ Sugg, Richard (1994). Jungian Literary Criticism. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-1042-3.

- ^ Rowan, John (1993). Discover your sub-personalities. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07366-9.

- ^ a b Rowan, John (1996). Healing the Male Psyche. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10049-6.

- ^ "British Museum headdresses". Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

- ^ Gage, Matilda (2008). Woman, Church and State. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60620-191-6.

- ^ a b c Murray, Margaret (2006). The Witch-cult in Western Europe (1921). Standard Publications. ISBN 1-59462-126-8.

- ^ Murray, Margaret (1970). The God of the Witches (1931). OUA USA. ISBN 0-19-501270-4.

- ^ Purkiss, Diane (2006). The Witch in History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08762-7.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2006). Witches, Druids, and King Arthur. Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-555-X.

- ^ "Cave Art Cobblers? – Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog". 6 July 2011.

- ^ Ginzburg, Carlo. Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath.

- ^ Russell, J. B. (1972). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. p. 37.

Other historians, like Byloff and Bonomo, have been willing to build upon the useful aspects of Murray's work without adopting its untenable elements, and the independent and careful researches of contemporary scholars have lent aspects of the Murray thesis considerable new strength.

- ^ a b Clifton, Chas; Harvey, Graham (2004). The Paganism reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30353-2.

- ^ Valiente, Doreen (2007). The Rebirth of Witchcraft. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7090-8369-6. Quoted in

- Clifton, Chas; Harvey, Graham (2004). The Paganism Reader. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 0-415-30353-2.

- ^ a b c d Luck, Georg (1985). Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Juliette Wood, "The Celtic Tarot and the Secret Traditions: A Study in Modern Legend Making": Folklore, Vol. 109, 1998

- ^ Herodotus, Histories ii. 42, 46 and 166.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories ii. 46. Plutarch specifically associates Osiris with the "goat at Mendes." De Iside et Osiride, lxxiii.

- ^ Budge, Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis (28 July 2018). "The Gods of the Egyptians: Or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology". Methuen & Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1991). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles. Blackwell. pp. 260–261. ISBN 0-631-17288-2.

- ^ Pearson, Joanne; Roberts, Richard H; Samuel, Geoffrey (December 1998). Nature Religion Today: Paganism in the Modern World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-7486-1057-X. OCLC 39533917.

- ^ Berger, Helen; Ezzy, Douglas (2007). Teenage Witches: Magical Youth and the Search for the Self. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4021-4.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2021). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-56228-9.

- ^ White, Eric (1996). "Once they were men: Now they're Landcrabs: Monsterous Becomings in Evolutionist Cinema", in Halberstam, J (1996). Posthuman Bodies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-253-20970-6.

- ^ a b Gibson, Marion (2013). Imagining the Pagan Past: Gods and Goddesses in Literature and History Since the Dark Ages. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-08254-3.

- ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1990). Understanding Contemporary American Science Fiction: The Formative Period (1926-1970). University of South Carolina Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-872-49689-7.

- ^ Sullivan, C. W. (May 1987). "Review: "Sword at Sunset"". Fantasy Newsletter. Boca Raton: Florida Atlantic University.

- ^ Callow, John (2017). Embracing the Darkness. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-786-73261-3.

- ^ Hunt, Leon (2001). "Necromancy in the UK: Witchcraft and the occult in British horror", in Chibnall, Steve; Petley, Julian (2001). British Horror Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23004-7.

- ^ Grant, Joan (March 1985). "Review: "Too Long A Sacrifice"". Fantasy Newsletter. Boca Raton: Florida Atlantic University.

- ^ van Dyke, Annette (1992). The Search for a Woman-centered Spirituality. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-8770-3.

- ^ Bernstein, Abbie (February 1990). "Legends of the Hooded Man : Richard Carpenter interview". Starlog. New York: Brooklyn Company, Inc.

- ^ Conroy, Mike (2004). 500 Comicbook Villains. Collins and Brown. ISBN 1-843-40205-X.

- ^ Morgan, Pauline (March 1985). "Review: "Black Smith's Telling"". Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Review Annual 1991. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- ^ Bramwell, Peter (2009). Pagan Themes in Modern Children's Fiction. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-230-23689-9.

- ^ Rennison, Nick (2012). Robin Hood : myth, history and culture. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1-842-43247-1.

- ^ Clute, John (2012). Stay. Beccon Publications. ISBN 9781870824637.

External links

[edit] Media related to Horned God at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Horned God at Wikimedia Commons