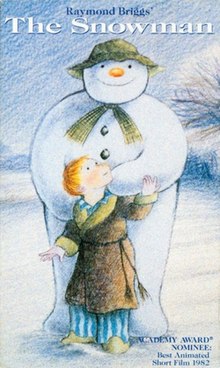

The Snowman

| The Snowman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Animation |

| Based on | The Snowman by Raymond Briggs |

| Directed by | Dianne Jackson |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Howard Blake |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Producer | John Coates |

| Running time | 26 minutes |

| Production company | TVC London |

| Original release | |

| Network | Channel 4 |

| Release | 26 December 1982 |

The Snowman is a 1982 British animated television film and symphonic poem[1] based on Raymond Briggs's 1978 picture book The Snowman. It was directed by Dianne Jackson for Channel 4. It was first shown on 26 December 1982, and was an immediate success. It was nominated for Best Animated Short Film at the 55th Academy Awards and won a BAFTA TV Award.

The story is told through pictures, action and music, scored by Howard Blake. It has no dialogue, with the exception of the central song, "Walking in the Air". The orchestral score was performed by the Sinfonia of London and the song was performed by Peter Auty, a St Paul's Cathedral choirboy.[2]

The film ranked at number 71 on the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes, a list drawn up by the British Film Institute in 2000, based on a vote by industry professionals.[3] It was voted number 4 in UKTV Gold's Greatest TV Christmas Moments. It came third in Channel 4's poll of 100 Greatest Christmas Moments in 2004. Its broadcast, usually on Christmas Eve on Channel 4, has become an annual festive event in the UK.[4]

A sequel, The Snowman and the Snowdog, was released in 2012.[5]

Production

[edit]Source book

[edit]The Snowman is a wordless children's picture book by Raymond Briggs, first published in 1978 by Hamish Hamilton in the United Kingdom, and published by Random House in the United States in November of the same year. In the United Kingdom, it was the runner-up for the Kate Greenaway Medal from the Library Association, recognising the year's best children's book illustration by a British writer.[6] In the United States, it was named to the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award list in 1979.

Adaptation

[edit]Iain Harvey, the film's executive producer and publisher at Hamish Hamilton, recalls that the book had initially sold well, but a second print had been less successful with 50,000 unsold copies sitting in a warehouse, which he attributes to the lack of dialogue preventing it being read as a bedtime story.[7] In 1980 he was contacted by producer John Coates from TVC (Television Cartoons) with an idea of adapting the book for an animated film, for which he gave his consent.[7][8]

In March 1982, Coates presented an "animatic" storyboard version with a basic piano track by Howard Blake, including an early version of "Walking in the Air" to commissioning executives at the fledgeling Channel 4, a new public service television company which was due to begin broadcasting in November 1982.[8] The director Dianne Jackson had worked with Coates on The Beatles' Yellow Submarine and had mainly worked on short animations and commercials; this was her first time directing a longer animated film. As a result, the experienced animator Jimmy T. Murakami was brought in to supervise.[7] The film was produced using traditional animation techniques, consisting of pastels, crayons and other colouring tools drawn on pieces of celluloid, which were traced over hand drawn frames. For continuity purposes, the background artwork was painted using the same tools.[7]

The story was expanded to fill 26 minutes and include a longer flying sequence which takes the boy to the North Pole and a party with Father Christmas which is not present in the picture book. The animators also brought in personal touches – a static sequence with a car is replaced by a motorcycle ride, as one of the animators was a keen motorcyclist and it was noted by Iain Harvey that this sequence kept "the action flowing after all the fun and comedy of the boy and the Snowman exploring the house and forming a friendship – and what could be better than a midnight run in a snowy landscape".[7] Similarly, although the boy in the book is unnamed, in the film he is named "James" on his present tag, added by animator Joanna Harrison as it was the name of her boyfriend (later her husband).[8][9] Interviewed in 2012, Raymond Briggs recalls that he thought "'It's a bit corny and twee, dragging in Christmas', as The Snowman had nothing to do with that, but it worked extremely well."[10]

The boy's home appears to be located in the South Downs of England, near to Brighton; he and the snowman fly over the Royal Pavilion and Palace Pier. Raymond Briggs had lived in Sussex since 1961, and the composer Howard Blake was also a native of the county.[2][11]

Music

[edit]The production team contacted Howard Blake early in the production, as they were having difficulties finding the right tone for adapting the wordless picture book. Blake suggested that the film should not feature dialogue, but instead a through-composed orchestral soundtrack. He recalls the song "Walking in the Air" was written some years earlier during a difficult period in his life, and the song formed the main theme for the work.[12][2] In 2021, Blake told the Financial Times that he wanted to incorporate the lyrics with "a symphony that expressed the complete innocence and beauty that we are all born with." Blake further brought up his religion, stating "It felt as though the idea came from God."[12]

Howard Blake's orchestral score was performed in the film by the Sinfonia of London.[2] The song "Walking in the Air" is sung in the film by chorister Peter Auty,[13] who was not credited in the original version. He was given a credit on the 20th anniversary version.

In 1985, "Walking in the Air" was covered by chorister Aled Jones in a single which peaked at number five on the UK Singles Chart. Jones is sometimes mistakenly credited with having sung the song in the film.[14] Blake's soundtrack for The Snowman is often performed as a standalone concert work, often accompanying a projection of the film or sometimes with a narrator (the version for narrator was first performed by Bernard Cribbins in Summer 1983).[15]

Plot

[edit]In a rural area of Brighton, after a night of heavy snowfall on Christmas Eve, a young boy named James wakes up and plays in the snow, eventually building a large snowman. At the stroke of midnight, he sneaks downstairs to find the snowman magically comes to life. James shows the snowman around his house, playing with appliances, toys and other bric-a-brac, all while keeping quiet enough not to wake James' parents. The two find a sheeted-down motorcycle in the house's garden and go for a ride on it through the woods. Its engine heat starts to melt the snowman and he cools off by luxuriating in the garage freezer.

Seeing a picture of the Arctic on a packet in the freezer, the snowman is agitated and takes the boy in hand, running through the garden until they take flight. They fly over the South Downs towards the Channel coast, seeing the Royal Pavilion and Brighton Palace Pier, and north along the coast of Norway. They continue through an arctic landscape and into the aurora borealis. They land in a snow-covered forest in the North Pole where they join a party of snowmen. They eventually meet Father Christmas along with his reindeer; he gives the boy a card and a scarf with a snowman pattern. The snowman returns home with James before the sun rises and the two bid farewell for the night as the snowman returns to his original position and becomes lifeless again.

The following morning, James wakes up to find that the snowman has melted, leaving only his hat, scarf, coal eyes, tangerine nose, and coal buttons in a pile of melted snow. A saddened James finds his scarf, indicating the events really took place and were not a dream, as he kneels down by the snowman's remains.

Alternative introductions

[edit]The original introduction on Channel 4 features Raymond Briggs walking through a field in rural Sussex describing his inspiration for the story, which then transitions into the animated landscape of the film (the idea being that he is doing so in character as an older version of James). The film's executive producer Iain Harvey had received interest in the film from U.S. networks and for a VHS release. However, he noted that "in the US programmes were sponsored, and to be sponsored you needed a big name". Various names such as Laurence Olivier and Julie Andrews were suggested, but a request for a rock star led to David Bowie being involved. He was a fan of Briggs's story When the Wind Blows and later provided a song for its animated adaptation. In the sequence, Bowie was filmed in the attic of 'his' childhood home and discovering, in a drawer, a scarf closely resembling the one given to James towards the end of the film;[8] he then proceeds to narrate over the opening with his own small variation of Briggs' monologue.

To celebrate the film's 20th anniversary, Channel 4 created an alternative opening directed by Roger Mainwood, with Raymond Briggs's interpretation of Father Christmas recounting how he met James, before giving his own variation on Briggs' monologue (including how the heavy snow left even him unable to fly) as he turns on his TV to watch the film, which the opening segues into.[16] Comedian Mel Smith reprises the role in this opening. This version is also cropped to fit a 16:9 widescreen format. Channel 4 used this opening from 2002 until Mel Smith's death in 2013, after which the Bowie opening was reinstated, which in turn returned the film to its original 4:3 aspect ratio.

Reception

[edit]Awards

[edit]The film was nominated as Best Animated Short Film at the 55th Academy Awards in 1983, but lost to the Polish film Tango by Zbigniew Rybczyński.[17] It won a BAFTA for best Children's Programme (Entertainment/Drama) at the 1983 British Academy Television Awards, and was also nominated for Best Graphics. It won the Grand Prix at the Tampere Film Festival in Finland in 1984.[17] It was named to the ALA Notable Children's Videos list in 1982.[18]

In the British Film Institute's 100 Greatest British Television Programmes, a list drawn up by the British Film Institute in 2000, based on a vote by industry professionals it was listed as #71.[3] It was voted #4 in UKTV Gold's Greatest TV Christmas Moments. It came third in Channel 4's poll of 100 Greatest Christmas Moments in 2004.

In a 2022 article, Stuart Heritage praised the film's visuals and themes, particularly noting how the final sequence reflects Briggs' theme that life is fleeting.[19]

Home media

[edit]The Snowman was originally released on VHS in 1982 by Palace Video. It has been re-released several times by Palace and later PolyGram Video, and Universal Studios Home Entertainment UK after Palace went out of business.

In 1993 it was released on VHS in the US by Columbia TriStar Home Video.

The Snowman was re-released in 2002 as a DVD special edition and again as a DVD and Blu-ray 30th anniversary edition in the United Kingdom on 5 November 2012 by Universal Studios Home Entertainment UK. The 2002 special edition peaked at No.3 in the video charts. The 2012 home video release includes four extra features: a "Snow Business" documentary, "The Story of The Snowman", storyboard, and the introductions used throughout the film's first 20 years. The film re-entered at No.14 on the UK Official children’s Video Chart on 11 November 2012, eventually peaking at No.5 on 16 December 2012 based on sales of DVDs and other physical formats.

The Universal DVD The Snowman & Father Christmas (902 030 – 11), released in the United Kingdom in 2000, uses the Bowie opening.[20]

Subsequent media

[edit]The Snowman and the Snowdog

[edit]To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the original short and of Channel 4, a 25-minute special titled The Snowman and the Snowdog aired on Channel 4 on Christmas Eve 2012.[21] Produced at the London-based animation company Lupus Films,[22] with many of the original team returning, the sequel was made in the same traditional techniques as the first film, and features the Snowman, a new young boy named Billy and a snow dog flying over landmarks and going to another party.[23]

The idea of a sequel had been resisted by Raymond Briggs for several years, but he gave his permission for the film in 2012.[24] Howard Blake was one of the few crew members not asked to return; he was allegedly asked to "send a demo", which he refused citing the success of the original score.[25] The new film instead features the song "Light the Night" by former Razorlight drummer Andy Burrows and incidental music by Ilan Eshkeri.[26]

The sequel was dedicated to the memory of producer John Coates,[27] who died in September 2012, during its production.[28]

Stage version

[edit]The Snowman has been made into a stage show. It was first produced by Contact Theatre, Manchester in 1986[29] and was adapted and produced by Anthony Clark. It had a full script and used Howard Blake's music and lyrics. In 1993, Birmingham Repertory Company produced a version, with music and lyrics by Howard Blake, scenario by Blake, with Bill Alexander and choreography by Robert North.

Since 1997, Sadler's Wells has presented it every year as the Christmas Show at the Peacock Theatre. As in the book and the film, there are no words, apart from the lyrics of the song "Walking in the Air". The story is told through images and movement.

Special effects include the Snowman and boy flying high over the stage (with assistance of wires and harnesses) and 'snow' falling in part of the auditorium. The production has had several revisions – the most extensive happening in 2000, when major changes were made to the second act, introducing new characters: The Ice Princess and Jack Frost.

Video game

[edit]Quicksilva published an official video game in 1984, for the ZX Spectrum,[30] Commodore 64, and MSX.

See also

[edit]- Granpa, Dianne Jackson's second animated film for Channel 4, with music by Howard Blake.

- Father Christmas – Briggs's earlier two works Father Christmas and Father Christmas Goes on Holiday were combined into a film which was released in 1991. It features the snowmen's party at the North Pole from this film, about a year or so after this film's events. The young boy and the snowman from this film are seen in the background during this segment.

- The Bear – another book by Raymond Briggs which was also adapted into a 26-minute animated version and like this film was conveyed through music and action.

- List of Christmas films

References

[edit]- ^ "The Snowman: A guide to the music of this festive classic - and who actually sang 'Walking in the Air' | Classical Music". www.classical-music.com. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Snowman". Howard Blake website. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ a b "The BFI TV 100 at the BFI website". Archived from the original on 11 September 2011.

- ^ "The Snowman". BFI screenonline. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "The Snowman and the Snowdog Story". thesnowman.com. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Kate Greenaway Medal". Curriculum Lab. Elihu Burritt Library. Central Connecticut State University. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "How The Snowman was built". BFI. 17 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d "How The Snowman melted David Bowie's heart". The Guardian. 22 December 2016.

- ^ Interview with Hilary Andus and Joanna Harrison in "Snow Business" included on the 2002 20th Anniversary DVD

- ^ "Snowman creator Raymond Briggs – grumpy old man or great big softie?". Radio Times. 24 December 2012.

- ^ John Walsh (21 December 2012). "Raymond Briggs: Seasonal torment for The Snowman creator". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ a b Brown, Helen (21 September 2023). "How Walking in the Air took The Snowman to great heights". Financial TImes. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Interviews with Peter Auty, Aled Jones, Raymond Briggs and John Coates on the making of documentary titled "Snow Business" included on the 2002 20th Anniversary DVD

- ^ For example: Barclay, Ali (4 December 2000). "The Snowman (1982)". BBC – Films. BBC. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ "The Snowman concert version". Howard Blake website. 23 November 2019.

- ^ "The Snowman". Toonhound. 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Awards". IMDb. 24 November 2019.

- ^ Notable children's films and videos, filmstrips, and recordings, 1973-1986. Chicago: ALA. 1987. ISBN 978-0-8389-3342-8. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2022/aug/10/well-still-be-watching-in-50-years-how-raymond-briggss-the-snowman-changed-christmas

- ^ (Despite being featured on the packaging. Some of the United States DVDs from Sony Pictures Home Entertainment don't have the David Bowie opening) "Customer Discussions: Review Comment Thread". Amazon.com. November 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Crump, William D. (2019). Happy Holidays—Animated! A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and New Year's Cartoons on Television and Film. McFarland & Co. p. 289. ISBN 9781476672939.

- ^ "The Snowman and the Snow Dog". Lupus Films. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Singh, Anita. "The Snowman and the Snowdog: a first look". Telegraph Media Group Limited 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "The Snowman and The Snowdog animator revisits classic". BBC News. 24 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Snowman composer told to submit demo tape for sequel". The Telegraph. 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Andy Burrows Announces Music Soundtrack To Channel 4'S The Snowman and the Snowdog". Contactmusic.com. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Barber, Martin (24 December 2012). "The Snowman and The Snowdog animator revisits classic". BBC News Online. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Snowman producer John Coates dies". BBC News Online. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ ""The Snowman @ The Lowry"". manchestereveningnews.co.uk. 16 April 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "Snowman, The – World of Spectrum". worldofspectrum.org. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1982 television films

- British animated television films

- Christmas television films

- Christmas in the United Kingdom

- British Christmas films

- 1982 films

- 1982 animated short films

- Fictional snowmen

- Films scored by Howard Blake

- Films about snowmen

- Animated films set in England

- Animated films set in Norway

- Animated films set in the Arctic

- Christmas television specials